Waking up on Monday to garbled – and, it turns out, less than accurate – reports that Japanese animation powerhouse Studio Ghibli was going to be closing its doors after 30 years in business was a strangely unsettling experience, coming as it did so closely after the announcement from its leading director Hayao Miyazaki that 2013’s serene The Wind Rises would be his last film. The influence that Ghibli has exerted on all forms of animation over the last three decades has been practically gravitational. (To put it in musical terms, imagine the same time period of left field music without the influence of Krautrock.) Ghibli’s widening of the perimeters of storytelling, commitment to technical innovation and ability to entertain audiences of all ages while, crucially, never talking down to or patronising them has resulted in the creation of some of the most sublime, frightening, beautiful and thought-provoking film-making ever. Not ‘animated film-making’ or ‘cartoons’, but ‘film-making’, full stop. And today’s cinematic landscape would be a very different place without them.

What always stood out for me when watching Ghibli films was the just-around-the-corner strangeness of them. Their drawing from Japanese storytelling and folk traditions ensured that Western audiences were never more than a few scenes away from being blindsided by an unexpected lurch into cruelty, or a sudden eruption of the grotesque. Love, in Ghibli terms, is found in the hardest and most dangerous landscapes, a world away from the certainties offered by Disney and the like. A film like Spirited Away is a genuinely frightening and confusing experience on first watch, but still it manages to draw all its elements together to a satisfying and uplifting conclusion while never sinking knee-deep into schmaltz. It is precisely this unexpected quality that has kept audiences hypnotized for the last three decades.

As mentioned above, it turns out that rumours of the studio’s demise were greatly exaggerated, and it’s even being rumoured the Miyazaki himself might make a surprise reappearance at some point. Whatever happens, now seems as good a time as any to look back over Studio Ghibli’s extraordinary thirty-year career and to ask our writers to select their favourite Ghibli films and discuss their choices. You can read the results below. If this is to be the end of Studio Ghibli’s ‘Stage One’ then let us hope that the next stage is as long, as illustrious and as innovative. Mat Colegate

Words by Yasmeen Khan, Rory Gibb, Matt Evans, Ed Gillett, Lisa Jenkins, James Ubaghs, Gary Green and Dale Berning

Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind

(Hayao Miyazaki, 1984)

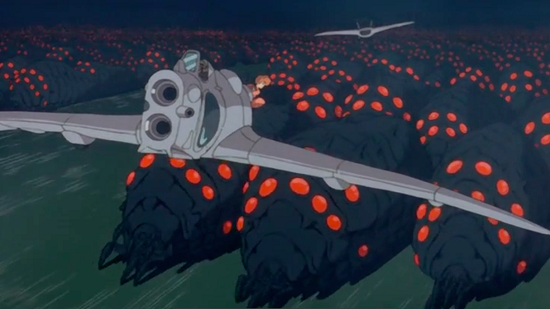

I only discovered Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind around the age of 20 or so, but I wish I’d come across it earlier. I’m not sure I could think of a more perfect film for my childhood self, whose early obsessions with wildlife, plants, conservation and collecting insects were later met by an intense fascination for science fiction. I have no doubt that, had I seen this as a kid – with its swarms of heavy-shelled arthropods, clouds of toxic spores and self-interested human factions all competing for existence in a poisoned world – I’d know it like the back of my hand by now.

Strictly speaking, the 1984 film of Nausicaä – based on Hayao Miyazaki’s 1982 manga series of the same name – was actually produced before the founding of Studio Ghibli in 1985. However, it’s usually recognised as part of the studio’s oeuvre, since its success was one factor in the decision to found Ghibli, and the themes it explores run throughout the studio’s later work: of humankind’s place within the planet’s ecology, of how our petty struggles for money and space are eroding away at the earth’s life support systems, and of what might happen if nature fought back. Pom Poko and especially Princess Mononoke would later further develop these concepts, and the latter especially is a viciously beautiful film about the conflict between nature and an ever-expanding human population.

But what I love in particular about Nausicaä is its refusal to impose human values upon its world’s ecology, avoiding that all-too-familiar and frustrating flaw that tends to blight many films dealing with nature (including, sadly, plenty of so-called ‘documentaries’). Here, every organism, whether human, animal or plant, exists on an equal footing. All are equally put-upon, all compete doggedly for resources and to protect their kin, all kill with impunity – there are no simplistic ‘good guys’ or ‘bad guys’ in this world, just situations of conflict, and myriad shades of grey. The insects that infest the planet’s toxic jungles aren’t the big-eyed, Disneyfied, anthropomorphised sprites we’re used to seeing in animation; they’re terrifyingly alien-looking, writhing masses of tentacles and compound eyes, yet often far more sympathetic than the flawed humans continually attempting to wipe them out.

Watch this alongside cutesy US films about deforestation like Ferngully or any number of hugely popular Disney movies centred around cuddly animal characters – where good is good, and the heroes always win in the end – and the difference couldn’t be more dramatic. Nausicaä‘s wholly realised, complex, three-dimensional world asks difficult, knotty questions of the viewer, realities and responsibilities you’re required to confront head-on. At a time when we desperately need young people to understand and engage with life on our increasingly threatened planet, this should be required viewing for all children over the age of 8 or so. Rory Gibb

Spirited Away

(Hayao Miyazaki, 2001)

The story of a little girl who finds herself adventuring in a dream, Spirited Away is Miyazaki’s Wizard of Oz or Alice in Wonderland. His heroine, Chihiro, is moving to a new town with her parents, but she’s miserable about leaving her old life. When her father makes a wrong turn just before their journey’s end, they walk into a world of spirits and sorcery. Chihiro’s parents are soon trapped by a spell, leaving her to negotiate the dream alone. Just like Dorothy or Alice, she must confront strange new rules and deal with inhuman tricksters and magic food, but she’ll find friends along the way and, eventually, learn something valuable about her real life.

Chihiro’s environment starts out bright and cheerful, and slips effortlessly into the richly magical. Miyazaki blurs the edges of the worlds so skilfully that the sensation of watching the opening sequence is not unlike falling asleep for real. He manages to conjure that sense of simultaneous comfort and danger that losing consciousness has; a transition into the dream landscape that is both enticing and disturbing. Here, Chihiro is safe, yet in peril – her new friend Haku reassures her that she will find her parents, but also warns that she’s an intruder in this world and must work to escape the anger of Yubaba, a Queen of Hearts-like ruling sorceress. The spirit world’s satisfyingly dreamlike physics confirm this sense – long falls and climbs up and down rickety stairs and ladders, flight, things that are impossibly heavy or light – and its internal logic has that same blend of too easy and too difficult, too safe and too dangerous.

Spirited Away has more than its fair share of anime adorableness, with its sweet little creatures and wonderfully cute detailing, but it works because it’s set off by some genuine grossness. The film’s filled with memorable images – the glowing boats, the spiders feeding the giant boiler, the water railway, Yubaba’s palatial corridors, the pig sty… The story’s about magic, but Miyazaki’s genius, like Carroll’s, is in creating a world of transformation and distortion that plucks at something universal in the experience of dreaming. Yasmeen Khan

Pom Poko

(Isao Takahata, 1994)

Something of a lesser-known curio in the Ghibli catalogue, Isao Takahata’s Pom Poko tells the story of warring groups of tanuki (Japanese racoon dogs) who band together to fight the encroachment of human civilisation into their untamed rural idyll. In Japanese folklore, the tanuki are shapeshifting, illusion-casting creatures of mischief – and the film revels in their supernatural powers via dazzlingly psychedelic displays of unfettered imagination that rank among the most spectacular visual feasts in the entire Ghibli canon.

However, this is an oddly pitched piece. Its furry central characters are extremely adorable and kid-friendly, but this is no simple children’s film. Its running time is extensive, its message heavily political, its levels of violence occasionally severe (the tanuki are only too happy to casually murder construction workers), and some of the shapeshifting set pieces verge on the mind-scarringly terrifying. Further complicating matters is the curiously prominent role played by the tanuki’s remarkably malleable scrotums, which are deployed as parachutes, boats and clubs, among other things – a delightful detail rooted in ancient Japanese folk tales, but initially startling to Western audiences. With its environmentalist theme, nightmarish dream/fantasy sequences and otherwise cutesy anthropomorphised animals engaged in harrowing and visceral life-and-death struggles, this is essentially the Japanese equivalent of Watership Down, only with magic powers and bollocks. Lots and lots of bollocks. Matt Evans

Castle In The Sky

(Hayao Miyazaki, 1986)

There a couple of different reasons why Castle In The Sky remains my favourite Ghibli film. For one, it was the first feature produced by the studio, and set many of the standards which would come to define it: hand-drawn animation of soaring imagination and dream-like beauty, an eccentric and bewitching cast of characters, and a heady mix of references and inspirations.

It has Ghibli’s first truly iconic image: the solitary robot marooned on the floating sky-island of Laputa, mournfully performing his endless rota of duties, oblivious to the decay around him. Laputa itself is that most Ghibli of settings: its otherworldly technology abandoned to the ravages of time and vegetation, it’s both a celebration of creative excess (in this case, a richly-designed steampunk aesthetic), and a wistful comment on the limits of human endeavour and understanding.

While Pazu and Sheeta are perhaps less fully-realised protagonists than those of later films, the supporting characters burst forth with glorious colour and energy: Dola and her haphazard crew of moustachioed sky-pirates, the relentlessly evil Muska and his crew aboard the Goliath, or the cryptic Uncle Pom, wandering through crystal caves deep underground.

Even better, though, is Castle In The Sky’s quietly subversive tone (which again became something of a Ghibli staple). Laputa’s name refers to Jonathan Swift, of course, while Pazu’s home town was inspired by a trip taken by Miyazaki to Wales in 1984. He’s spoken of wanting to honour the people and communities he saw there, and their dignity in the face of being forcibly disappeared by Thatcher’s reforms.

Castle In The Sky is thus not only a work of gleeful beauty and invention, but also expresses a nuanced and deeply affecting social perspective. Compare this to Disney, who back in 1986 would have been hard at work on the colourful but vapid The Little Mermaid, and the contrast becomes obvious: right from the start, Ghibli was aiming for something beyond the ordinary. Ed Gillett

Howl’s Moving Castle

(Hayao Miyazaki, 2004)

There is a delicious expectation when watching a Studio Ghibli film. You know that alongside the sweet voices and mesmerising animations, lies a dark twin. Monsters lurk to teach lessons and the stuff of childhood nightmares will pop up when least expected. Howl’s Moving Castle [based on the book by Diana Wynne Jones] does not disappoint. This was the second Studio Ghibli film I saw and it reminded me of the old Hans Christian Andersen stories, with a touch of Grimms’ Fairy Tales thrown in. ‘Red Riding Hood’ meets ‘Hansel and Gretel’. Sweet on the outside, but with a much darker story to be told.

Keeping with Hayao Miyazaki’s definitive style it is instantly recognisable as a Studio Ghibli film. A headstrong girl follows her heart, falls in love with a complex boy, fights demons, breaks ancient curses and all while holding onto her principles. Of course I’m simplifying things, but a strong moral code of conduct runs through all Miyazaki’s films. Howl’s Moving Castle is different in the respect that it is based on a previously written book and changes have been made in the film’s creation. However it lends itself so well to Studio Ghibli that it could have been an original. One of the more in-depth story lines they have tackled, this has been beautifully adapted and imagined. I can’t help wishing Studio Ghibli had tackled the likes of ‘Red Riding Hood’ and made the original fairy tale far more interesting. I can also only hope that this is just a hiatus for them, and not an end to one of the most original, forward-thinking studios in film. Lisa Jenkins

My Neighbor Totoro

(Hayao Miyazaki, 1988)

My Neighbor Totoro is a special film. It can just as easily hold a toddler’s attention as it can a parent’s – or a hung-over twenty-year-old’s – and it manages to do so while being essentially plotless and conflict-free. This low-key, beguiling, magical film may very well be Hayao Miyazaki’s masterpiece.

The story, such as it is, involves two young girls and their father moving to the countryside in order to be closer to their recovering sick mother – a premise that draws on Miyazaki’s own childhood experience of having a mother afflicted with spinal tuberculosis. Their new home is haunted, or blessed, by friendly acorn-eating spirit/animal creatures (the Totoros of the title) that the children discover and interact with.

And that’s pretty much it. There are no quests, or villains, or needless challenges to overcome; just the quotidian minutiae of life and the beauty of the natural world, experienced through a genuinely childlike perspective of innocent wonder. When the Totoro creatures do appear it’s not loud or brash. They just are, and simply watching them is magical enough.

Take the iconic bus stop scene for instance: Totoro nonchalantly appears in a quiet moment of pause, and its gentle befuddlement is a beautiful and alien, yet weirdly poignant, thing to witness. He then gets on a catbus. A bus that is actually a cat. My Neighbor Totoro features a catbus. Just think about that for a moment.

What elevates the film even further is its unobtrusive sense of underlying melancholy. It’s understated, and will likely fly over younger viewers’ heads, but it’s there. The mother’s illness is never stressed upon, save near the end, but a parent’s mortality is presented as potentially terrifying reality; one that you just have to accept and live with. There’s a scene when the younger girl briefly goes missing. After finding a discarded child’s shoe in a pond, villagers trawl the water with nets. What they’re looking for is left unsaid, but it’s quietly devastating, and all too real when the realisation hits.

Of course everything is fine in the end, it’s not that kind of story (unlike the unbearably upsetting Grave Of The Fireflies with which Totoro was originally released as a double bill, a fact that boggles the mind). No one dies and life goes on. And that’s just as magical a thing as a Totoro riding a catbus. James Ubaghs

Grave Of The Fireflies

(Isao Takahata, 1988)

Setsuko and Seita. It’s difficult to forget those names, even years after your first viewing of Ghibli’s tragic requiem for the Japanese victims of World War II, Grave Of The Fireflies. Isao Takahata’s first movie with Studio Ghibli doesn’t share the same daydream atmosphere as My Neighbor Totoro, but then that was entirely the point.

Grave Of The Fireflies is a ghost. Not only is it filled with them, but the film itself wanders around looking for a purpose, like its two central adorable, tragic characters. The audience is in mourning, not just for Setsuko and Seita, but for an entire country. Roger Ebert said that it “belongs on any list of the greatest war films ever made” and it’s hard to think otherwise. Many war pictures tread around the subject of the loss of innocence, but Grave Of The Fireflies is one of the only films to really nail the point home, and painfully so: these kids didn’t have a chance to grow up, to fall in love, to have children of their own. It’s not just that they had their lives stolen from them. The true crime of war is that they had stolen from them everything they could have ever been.

Grave Of The Fireflies is a masterpiece. It’s an ode to the medium, which showed many that animation can be cinema at its purest. Totoro may be on the studio’s logo, but it’s Setsuko and Seita’s presence that is felt most keenly throughout Ghibli’s oeuvre. Gary Green

Ponyo On The Cliff By The Sea

(Hayao Miyazaki, 2008)

This is one of the rare Studio Ghibli films that I didn’t love the very instant I first saw it. I’d been bewitched by the strength and edge to Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä…. I’d fallen for Future Boy Conan, Hayao Miyazaki’s bleak pre-Ghibli creation. And Mei and the catbus and Totoro were simply too wonderful to comprehend. By comparison, Ponyo On The Cliff By The Sea felt flat and simplistic and saccharine, a bit like ice cream melting on a humid day. Mostly the magical world felt thin, incomplete. And then the little things crept up on me and drew me in – the way five-year-old Sōsuke crouches down on his haunches to peer into his green bucket and check if the goldfish he’s just rescued is still alive; the way he walks past his friends, the old ladies in the care home where his mother works, concentrating on the bucket and telling them he’s just a bit busy but he’ll be back soon to see them; the way he is so mature and caring and suddenly just a tiny boy, distraught, as his mother scoops him into her arms when he loses the goldfish – who he’s named Ponyo – to the ocean…

The magical world here is a mere backdrop to a story built of slight, daily moments and familiar feelings, beautifully and carefully rendered with a precision that lends them depth and poignancy. Miyazaki is a master of many, many things. But his skill in making a light turn on just the way lights do – a slight pause before the fluorescent tube clicks alight; in capturing a small child’s gentle movements and an old lady’s wistful speech – his ability to sketch the ordinary into animated life – is astonishing, and never more evident than it is here.

I often forget about the epic ocean drama in which Sōsuke and Ponyo’s friendship is couched, but every time I see a little kid bending down to pet a cat or two children examining a treasure of some kind, it’s the boy and his goldfish friend I’m reminded of. Dale Berning