"Why me, Lord?"

Friends occasionally remind me that if they called my number in late 1994 and found only my answering machine, that was the outgoing message that greeted them. A brief, acoustic strum, followed by the unmistakable baritone of Johnny Cash, with that gnomic rhetorical question. Then the beep. I wasn’t having the best time of it. Nor, as it happened, had Cash been, until not long before.

It was originally Kris Kristofferson’s question, and we’ll come back to that. But Cash made it his own. We’ll come back to that, too. Both are important aspects of American Recordings, an album whose effect on Cash’s career and on popular music as a whole and whose canonic stature exceed, in hindsight, its many qualities as a piece of work.

And it is a wonderful piece of work, have no doubt. Yet of the six-strong series of albums it begat – records of varying magnificence – it isn’t my favourite; I’d pick Solitary Man and the posthumous release Ain’t No Grave, and perhaps The Man Comes Around, ahead of it. But that, again, is to jump ahead. In 1994, it was revelatory. In terms of impact and influence, it still stands far above the others.

To understand where Cash was at that point, it’s instructive to refer to Out Among The Stars, recordings he made under the guidance of Countrypolitan producer Billy Sherrill ten years previously, which were released only this year. Between the late 50s and the early 70s Cash had established himself among the greatest artists of any genre. Thereafter, he had started to seem a man out of time, scampering with regrettable indignity to catch up with where country was going, and always seeming to get there after it had gone. Out Among The Stars was a low point. It has its moments – it’s still Johnny Cash, after all – but even in 1984 it would have sounded dated, and it is by turns so mawkish, gimmicky and cornball one could imagine him performing selections from it on The Simpsons’ Hee Haw spoof Ya-Hoo! alongside Yodelin’ Zeke, Gappy Mae and Big Shirtless Ron.

By the time the 90s rolled around, it was only in tandem with supergroup The Highwaymen that Cash, for all he was revered, could sell records to anybody. His brief solo stint on the Mercury label had been a flop. He looked like a performer with nowhere new to go. In a way, he was. It was his good fortune, and Rick Rubin’s shrewdness, to understand that in that fact lay the key to Cash’s artistic and commercial resurrection.

Rubin, the ingenious rap, rock and metal producer, co-founder of Def Jam records and progenitor of the breakaway Def American label, was also looking to make a change. He planned to rename his label American Recordings, and wanted to expand its repertoire. He already had a country-rock act – The Jayhawks, whose 1992 album Hollywood Town Hall would become a milestone in what was not yet called alt.country – but Cash was something else again: a beloved, bona fide legend on his uppers in the industry, an artist with extraordinary talent and cachet who needed Rubin as much as Rubin needed him.

Rubin’s essential insight was what to do with a man out of time: present him as timeless. What were the qualities of Cash’s greatest work? Its spareness. The way it combined the aura of its origins with the modernity of its moment. Cash had gone awry trying to pursue modernity when it eventually, and inevitably, escaped him. Making a virtue of necessity, Rubin discarded that part. Chasing it was a lost cause. But that spareness, that aura – those were there for the exploiting. The producer of so many exhilarating, cranked up records made a Johnny Cash album as stripped-down and low-key as it conceivably could be. Songs, voice, acoustic guitar. It was a masterstroke.

What it did was create a whole new modernity, one cannily disguised as anything but. It wasn’t a straight country record, or bluegrass, or folk, or anything immediately recognisable. It wasn’t a covers album, although it featured only four Cash compositions. So you couldn’t call it a singer-songwriter album either. It was a statement; almost a stark monumental sculpture of an album, a chiselled ideal of what Cash represented in American life and culture.

The tracks ranged from old-timey murder ballads (the opening ‘Delia’s Gone’, a seemingly traditional number credited to – that is, likely adapted by – a pair of 50s folk musicians, and first recorded by Cash in 1962) to the self-satirising country drollery of closing number ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Cry’, written by the impish Loudon Wainwright III. There were songs composed for Cash by Nick Lowe, Glenn Danzig and Tom Waits. There was ‘Tennessee Stud’, a cowboy’s love song to a horse, once a kitschy Western hit (yes, the album features both kinds of music) for Nashville sound star Eddy Arnold. And there was Leonard Cohen’s ‘Bird On A Wire’, the ‘My Way’ for bohemians, austerely rendered far more sufferable and convincing than Cohen’s own rather self-serving version.

A remarkable variety of material, then, but what was consistent was the tone. Cash had yet to assume quite the gravitas he would impose upon the later albums, which would see him personify that quality, but it was sombre, it was steady, it was never played just for laughs even on the lighter songs, and – unlike Cash’s 60s dabblings in Dylanism – it sounded beholden to no one.

Except it was, and this is no bad thing, any more than the Dylan phase had been. (And that itself was fair exchange and no robbery.) It was just a less obvious source. Kris Kristofferson’s role in outlaw country is well recognised: The Highwaymen, made up of its foremost exponents, Cash, Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, surely weren’t thus named by accident. Perhaps less acknowledged is his particular role in Cash’s career. The finest songwriter among his peers, Kristofferson owed a great deal to Cash’s support, and he amply repaid it with ‘Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down’. Seldom did anyone perform Kristofferson’s compositions as well as Kristofferson. Numerous country stars had hits with his songs; few are as memorable as his own takes.

Cash, though… when he covered a song, it stayed covered. His ‘Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down’, as heard on his TV variety show (on which he refused to take out the allusions to marijuana), became the definitive version, a huge country hit, and one of his signature tunes. As U2, Trent Reznor, Neil Diamond, Nick Cave, Will Oldham, Martin Gore and Sheryl Crow would discover, Cash didn’t merely borrow your songs. At the very least you would cede spiritual co-ownership of them, and quite possibly you would have to resign yourself to your own version vanishing into the recesses of the common consciousness, to be supplanted by Cash’s.

‘Why Me Lord’ was Kristofferson’s biggest solo hit. It belongs to Cash now. I doubt Kristofferson minds, given their friendship and the long intertwining of their careers. The legend has been much retold of how the Columbia studio janitor and part-time helicopter pilot got Cash’s attention, after many thwarted bids, by landing his aircraft on the latter’s lawn to deliver a stack of tapes. (Kristofferson has said this is true, but that Cash wasn’t at home.) A curious twist to their back story was revealed with the release in 2010 of Please Don’t Tell Me How The Story Ends, Kristofferson’s publishing demos from the late 60s and early 70s.

When I heard what was, presumably, on those tapes Kristofferson gave to Cash, I was struck by how strongly it prefigures American Recordings. Then again, it would – but for Cash, Kristofferson would never have sounded like Kristofferson. Yet in turn I now find it unimaginable that Cash did not know how closely he was steering to the plain, direct, rasping, understated sound and spirit of those demos. American Recordings now seems to me the culmination of two-and-a-half decades of symbiosis. Perhaps it’s fanciful to attribute so much of it to that, and Cash is no longer around for anyone to ask; but I find myself unable to hear it any other way.

Kristofferson has, as a performer, always been something of a cult figure. Cash was a giant. Kristofferson might have made this album and it would have had scant effect on anything. Cash made it and it transformed everything around him.

Countless artists had made albums that sounded like a contemplative man singing along to a lone acoustic guitar in an empty room, because that’s what they were. But nobody had ever made one that sounded like Johnny Cash doing it because that’s what it was. American Recordings was, apart from everything else, one of the most brilliant pieces of marketing the music business has produced in recent memory. The title was perfect, on every level, and perfectly promoted its renamed label – a trademark of a record, making an outrageous yet all the same justifiable claim. American Recordings. Think about everything that implies. Who else but Cash could have carried it off?

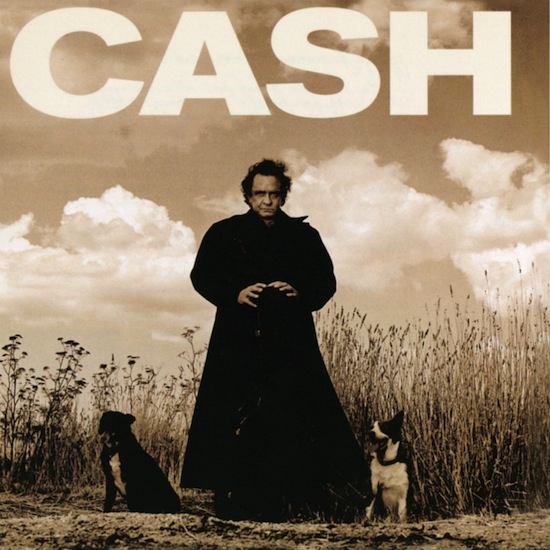

The presentation was likewise inspired. The monochrome sepia portrait of Cash in a full-length duster coat, flanked by dogs and framing what only the glinting hinges revealed as his guitar case, set against spacious skies and what weren’t exactly amber waves of grain but at least hinted there might be some nearby, beneath simple, stern capital letters offering only the information: CASH. It was elemental: Cash as a force of nature, rising from American soil with a mountain’s majesty. It wasn’t just powerful: it was, to invoke correctly a much abused term, iconic. Iconic enough to augment, to surpass, to replace, Cash’s previous and now tarnished iconic image. Think of him now, and almost certainly you think of him like this. Even the aforementioned release of Out Among The Stars, an album that by rights should have featured a cheesy, grinning Cash on a neon-rimmed cover design, copied the formula as closely as it could without risking an intellectual property suit.

American Recordings accomplished one of pop’s neatest paradoxes: it invented a form of authenticity. The music and imagery on it are no more innately "authentic" than, say, those on a Girls Aloud album. All pop is by its very nature synthetic. Some of it celebrates that fact; some of it belies it. There’s nothing wrong with doing either. The salient question is how well you bring off the desired effect. If anything in pop has ever succeeded so well as American Recordings in conjuring up the notion of the authentic, in defining in so many people’s minds what the authentic must consist of, I can’t guess what. It was a superlative act of myth-making, one for which many other veteran artists have since been grateful. Until then, you had to be an old blues dude to be taken seriously over a certain age by anyone other than your original audience.

The "heritage act" industry is thus indebted to Cash, but the wonder of the American Recordings series is that it both sought and achieved the antithesis of money-spinning back catalogue regurgitation. It ranks among the most glorious late bloomings in the career of a cultural titan, alongside Philip Roth’s American Trilogy or Claude Monet’s water lilies. You may have your own opinions, as I do, on which are the best of those albums. But I don’t think there’s any disputing the unrivalled significance of the first.