I should imagine that, when it comes to Oasis, Quietus readers fall into two distinct camps. The first group, schooled in the well-trodden debates of the last twenty years, from John Harris’s The Last Party to Simon Reynolds’ Retromania, is probably inclined to view Oasis as, at best, a vulgar superstructural expression of the Blairite phase of neoliberalism; and at worst, a sublime travesty of the whole meaning of progressive art, politics and human endeavour.

I don’t want to completely reject this view, for which there is some justification. However, there is a second, more interesting group I think, whose perspective is worth seeking out, and whose ambivalence about Oasis is likely to have been piqued by the recent avalanche of retrospective comment features in recent weeks dedicated to the strange, conflicted year that was 1994.

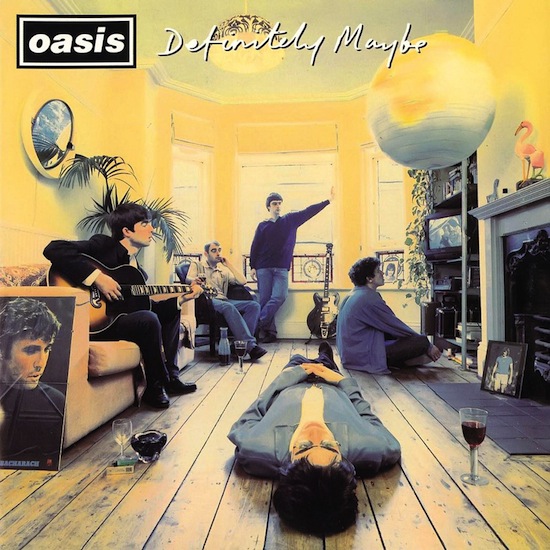

The 20th anniversary of Definitely Maybe (which is also, as you might have noticed, the 20th anniversary of Britpop as a whole) gives those of us who loved Oasis at their inception in the mid 90s – and those of us who have always dismissed them out of hand – a chance to reconsider matters. Did the Gallaghers’ headlong descent into tabloid farce and creative decay post-…Morning Glory really irrevocably undermine everything that was energising and radical about their project in the first place? Or can the early Oasis narrative be redeemed in spite of its disastrous legacy?

Any defence of Oasis, of course, must centre on their August 1994 debut, which has just been reissued and repackaged in a deluxe 3CD format. A book I’ve written for the 33 1/3 series about Definitely Maybe (an extract from which is published along with this piece) goes into quite a bit of detail about the minutiae of the songs, the class politics, the historical backdrop to the album’s gestation and so on. To avoid merely rehashing the book’s arguments, I’ll try to focus here mainly on the strengths and weaknesses of the reissue itself.

Although Definitely Maybe: Chasing The Sun Edition is predictably flabby and mostly gratuitous (as commercially motivated re-releases tend to be), it also highlights some of the things that made Oasis’s debut such a powerful sonic statement on its original release.

Unfortunately, it often achieves this feat negatively. A properly remastered edition of Definitely Maybe was always going to be a more than usually interesting prospect because of the album’s famously fraught recording history. To start with, Definitely Maybe was in a significant sense an album without a producer, a fact that some people will find delightfully postmodern while others might cynically argue is all too apparent. Mark Coyle, a friend of Noel Gallagher’s who became Oasis’s soundman in 1993 after a stint touring with Teenage Fanclub, is down on the inlay booklet as official production head. This is only partially true. Creation initially recruited veteran producer Dave Batchelor to supervise recording sessions at Monnow Valley Studios in South Wales, but the resulting tapes were judged to have suffered from the use of too many click-tracked overdubs – a lousy way to recreate the band’s combative live drone (listen to the rather feeble Monnow Valley version of ‘Bring It On Down’ included in the reissue for conclusive proof of this).

Coyle then took charge alongside Noel Gallagher and engineer Anjali Dutt (she of Loveless fame) as the sessions relocated to Sawmills Studios in Cornwall. Although the emphasis on simultaneous performance – and the resulting ‘spillage’ between tracks – at Sawmills produced a much more powerful set of recordings, a sense remained that something had been lost in the transition between live and studio environments. Creation therefore handed the tapes to Owen Morris, who worked alone in post-production on the Sawmills recordings (as well as a couple of earlier demos, and one song, ‘Slide Away’, from Monnow Valley) until they were deemed to have realised Noel Gallagher’s ambition that the album should sound "like an aeroplane taking off".

The problem with the remastering job on Definitely Maybe 2014 is that it brings the songs back somewhere close to the classic-rock orthodoxy of the Monnow Valley sessions. Morris’s roaring ‘brickwall’ mixes, with their excessive use of compression, tape delays, tambourine samples, harmoniser effects and varispeeding, were part of the reason the original version of the album sounded so vital, so punk. Although the difference is subtle, the remix has noticeably smoothed out the rough edges of Definitely Maybe‘s egregious torn-speaker onslaught, producing a sanitised collectors’ edition more in keeping with the compromised morals of Oasis post-1996 than those of the bellicose dole band of 1993-4.

So much for CD1. CD2 is slightly more worthwhile, because it collects together the regularly brilliant B-sides from the Definitely Maybe campaign. At their best – the catatonic grandeur of ‘Listen Up’, the Tony Benn-sampling white label version of ‘Columbia’, the pile-driving Mixolydian riff in ‘Cloudburst’, the glorious accelerated melancholy of ‘Fade Away’s chorus – these songs demonstrate the sheer effortless elan of Oasis at their pre-dadrock peak. On the other hand, all of these recordings have been widely available since they were released in 1994, and the remixing job has once again left them sounding pretty lukewarm. The new versions might fit snugly into the middle of an iTunes playlist, but they have none of the egregious mid-fi velocity of the originals.

By far the best material on this release is contained on CD3, which juxtaposes the demos from a 1993 cassette tape called ‘Live Demonstration’ with a handful of interesting live versions. The demo of ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’ – complete with loveably post-adolescent Liam Gallagher vocals – is poignant for its half-baked fragility, not least because its desperate idealism only really makes sense when it isn’t being sung by a millionaire rockstar. The only previously unreleased composition in the whole package, ‘Strange Thing’ draws a suggestive line of influence back to the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays, as does a sketchy first draft of ‘Cloudburst’.

Meanwhile, the version of ‘Supersonic’ recorded at Glasgow Sound City makes the most of that song’s neo-psychedelic brutalism, and underlines just how vigorously weird Oasis must have sounded to live audiences in 1994 – a sort of bastard child of shoegaze, punk, glam rock, the better Manchester bands and mangled jukebox populism. As the Sound City performance winds down, Britpop spin-doctor Jo Whiley can be heard uttering breathless hyperbole to Radio 1 listeners, and the nightmare postscript to Definitely Maybe hovers ominously into view. But it would be a shame if we followed Whiley and her ilk by treating Oasis as just another group of sell-out cock-rockers. Even on this largely pointless cash-in, the subtler, riskier truth about these curiously effusive songs is not all that difficult to recover.

An Extract From Al Niven’s 33 1/3: Definitely Maybe

Definitely Maybe is indebted to both grunge and shoegaze in a number of ways, some superficial, some more profound. The grunge influence entered the album largely by way of Noel Gallagher’s somewhat grudging respect for Nirvana’s Nevermind. Although, lyrically, Gallagher’s humanism was apparently a deliberate reaction to Kurt Cobain’s deadpan nihilism (see especially the Nirvana song ‘I Hate Myself And Want To Die’), when it came to actual music there was a large amount of common ground between the two. In fact, there was even a loose personal connection linking Gallagher and Cobain: Mark Coyle, Gallagher’s best friend and co-producer during the Sawmills Studio sessions for Definitely Maybe, toured with Nirvana in 1992 as sound engineer for their support band Teenage Fanclub (another Creation act).

Whether or not Coyle carried over anything from this experience into his production work on Definitely Maybe, there are a number of moments on the album that speak of an affinity between Oasis and their Seattle counterparts. ‘Slide Away’ adopts the classic grunge technique of combining a heavy rock base with a melody that alludes to Neil Young and The Beatles. On a smaller scale, the leaden power chord sequences in ‘Supersonic’ and ‘Bring It On Down’ are heavily reminiscent of those on Nevermind. So, too, are the phaser effects used to treat many of Noel Gallagher’s overdubbed lead guitar parts. Phasing is an electronic effect that produces two slightly different copies of the same note. Throughout Nevermind – and especially on its lead singles ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ and ‘Come As You Are’ – Cobain uses phasing and the very similar ‘chorus’ effect to create a swirling, underwater guitar sound. Reportedly with the aid of the Boss PH-3 Phase Shifter, Gallagher replicates this underwater tone fairly often on Definitely Maybe, notably in the solo halfway through ‘Shakermaker’, in the outro to ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’ and in the main guitar line that eddies throughout ‘Columbia’. Indeed, divested of its twelve-bar-blues references and kitchen-sink allusions (‘Shakermaker’s’ collage of British consumerism, Liam Gallagher’s Mancunian vowel palette), Definitely Maybe might almost be mistaken for a grunge record. Cobain’s ambition for Nirvana was to combine the melodic subtlety of The Beatles with the hard-rock dynamism of Black Sabbath, and Oasis achieved a very similar synthesis in their early compositions, although their interest in the Sex Pistols and glam rock contrasted subtly with Cobain’s taste for seventies metal.

The shoegaze influence in the early Oasis sound is just as pronounced as the debt to the grunge of Nevermind. Although they were viewed as something of an anomaly within the shoegaze label Creation, Oasis were nevertheless a neo-psychedelic rock band with a taste for distorted guitars and classic sixties pop, so in fact they fitted in relatively well with the Creation house style. Moreover, being connected to the Creation stable along with My Bloody Valentine, Ride and others meant that Oasis rubbed shoulders with a number of people who had been influential in establishing the shoegaze sound. Perhaps chief among these was Anjali Dutt, the main sound engineer on both My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless and Definitely Maybe (as well as records by Swervedriver, Spacemen 3 and the Boo Radleys). Dutt’s involvement in the studio brought a much-needed element of nuance to the album, an emphasis on the cerebral and the textural that seems to have been carried over partly from her experience of working with the shoegaze bands.

But the major shoegaze influence on Definitely Maybe arrived from a source outside of Creation. Throughout the last weeks of 1993, Oasis toured with Verve (later to be renamed The Verve), a band formed in Wigan, just outside Manchester, who were heavily associated with the shoegaze sound at this point. While My Bloody Valentine and the Thames Valley bands were probably too culturally distant from Oasis to offer any direct inspiration, Verve were from a broadly similar background, and hence much more easy to assimilate into Definitely Maybe‘s pot of influences.

Verve’s 1993 debut album Storm In Heaven is far more esoteric than anything Oasis ever produced. But with hindsight it sounds very much like a darker, weirder cousin of Definitely Maybe, and it seems likely that Oasis’s experience of touring with Verve on the eve of the early 1994 recording sessions was part of the reason for the similarity. Noel Gallagher almost certainly stole the title of ‘Slide Away’ from the Storm In Heaven track of the same name, one of the biggest indie singles of 1993. Oasis and Verve also shared an almost identical visual aesthetic: the Brian Cannon/Michael Spencer Jones partnership designed all of the early Verve cover sleeves, and many of these ideas would later be recycled and refracted in their artwork for Oasis.

Most importantly of all, Storm In Heaven‘s echo-drenched guitar textures provided another model of how indie rock might be made to sound expansive and all-encompassing on record after a period in which it had largely been content to be marginal and recondite. In seeking to achieve the engulfing wash of sound on Definitely Maybe, Oasis drew heavily on Verve guitarist Nick McCabe’s latter-day acid-rock techniques, from his reliance on delay and reverb effects to the use of slide guitar as a psychedelic device. Brian Cannon’s cover for Verve’s second single ‘She’s A Superstar’ featured a photograph of a cascading waterfall. This was an embodiment of the sort of romantic grandeur Oasis would try to emulate and extend.

Definitely Maybe: The Chasing The Sun edition is out now. Al Niven’s 33 1/3 book Definitely Maybe is published by Bloomsbury and is available from Monday July 7th. There is a launch party featuring a 1994 themed DJ set by tQ scribe David Stubbs at the Peckham Pelican on July 16th