I cannot remember my father’s ears. I remember my mother’s, however.

The crew, they ask me questions. Not so much an interrogation. They call it an interview. I cannot use my legs.

Who has robbed me of the use of my legs?

Time, of course.

And the crew, why do they ask questions?

What do you remember they say and I say: not my father’s ears.

To think of famous ears: see Van Gogh, a switchblade cutting his ear off. Think of your own career as a painter. A painter, I am.

I am not a red haired Dutchman.

But I have lived in Brixton. Or so they tell me. The documentary crew surrounds me. They tell me of my past.

They remember more than I do.

I lived in Brixton and smelled my mother’s ears. Remember when you were four years old: the smell of her ears has never left you. The smell – still in the back of your throat.

The throat was always my favourite part of the human anatomy.

In fact, I do not remember much about my father. Did we speak the same language?

My memory fails me in old age. How old am I?

The documentary crew intern tells me I do not look a day over 30. Which is a nice thing to say.

The mirror does not lie. Or does it? The paintings definitely lie. Consider the self-portrait, painted in 1967.

One often defines oneself as what one is not.

Must I use the antiquated ‘one’ when I could probably – definitely – substitute it with the more contemporary ‘People’.

I am not Van Gogh, yes. I am not a good father.

I am famous.

I am the famous throat painter.

My father, what colour was his hair? Was it white? Was it black? Surely it had colour, once? Surely his hair was once coloured and, in time, lost that colour? Do I generalize the father?

The father or My father?

What is the point of enjoying the present?

I read a book once. A homily on boils and carbuncles. Medieval bloodletting techniques and removal of anal fissures.

Was it for research, I wonder? Or was it Father’s doing?

I forget things, the doctor tells me. My doctor tells me he likes my paintings. Of course, maybe he is massaging one’s ego.

To think of all the geniuses who died in penury.

A mind that was once like a sponge has lost its sponge-like quality. In my youth, the obsession for remembering things. The importance placed upon remembering the births of artists and the deaths of artists.

But not so much the deaths of people who are not famous. Not so much the deaths of people who achieved relatively little.

Is there a problem with living a life and achieving nothing?

Well, of course, define nothing.

Well, of course, define achieving.

My son said he loved me, somebody told me. I told my father I loved him. But did he understand?

Define love.

Think of his country of birth and think, if you can, of omission. The meaning of leaving things out.

He was a presence, but a silent presence. Think of popular culture. Yes. The monolith in A Space Odyssey. The monolith as Father.

To get ahead as an artist, one must not have any distractions. I was, as a young man, a highly competitive man.

To see others succeed made me sick and I wanted to kill them. I often dreamed of killing my contemporaries.

Kill Your Contemporaries is the name of the documentary, incidentally.

And you cannot have distractions as an artist, no. A wife, no, children, no. Omissions are necessary.

But regrets, I have.

Though, most of my life is spent indoors now. Art thrives indoors. Think of the rain. What art survives the rain? Painting, no. Books, no. Film, no. The artist survives in water, but his art does not.

Stay on the inside.

My wheelchair is excellent. Sometimes, in this wheelchair, the useless facts of the past come back to me and have no relevance to the present.

The death of Renoir. Or the death of Juan Rodolfo Wilcock. The death of Claude Monet in 1926 due to lung cancer.

What is the point of knowing any of this? Why, as a young man, did I deem this knowledge useful?

The use of my legs is sorely missed. I think to myself: the places I could have travelled if I had legs.

Though, one must note the irony in the loss of one’s legs: I have travelled to more countries, disabled, than I have ‘abled’.

Herman Melville died having not made more than $10,000 from his writing. Edgar Allen Poe died aged 40, a drunk, a lush, in the pits of Baltimore.

To think I have worked all my life to forget what I have worked for.

My mother also had the biggest dugs you have ever seen.

Where was I born?

Was it Baltimore? Was I born the day Poe died?

Or was it London? Was I born out of wedlock? To think of my mother as a murderer who changed her ways.

I imagine my wife as a child-killer, a committer of infanticide, written in the style of the Old Bailey court proceedings:

A woman, whose age might have promised more chastity and prudence, being privately delivered of a bastard child, made shift, by her wickedness, to deprive that poor infant of a life. She had concealed the infant under her pillow for a week.

I say imagined. Perhaps this was not reality.

How do you tell what century it is? From looking out from one’s window? I see what many people deem to be an automobile.

I see cars. I see, inside my room, young people. The youth of today looks like the youth of yesterday and will probably look like the youth of tomorrow.

John Singer Sargent died of heart failure in 1925. And let’s not talk about Ferdinand Barbedienne.

They say my son is out of sight, out of mind. Which is to say he is missing.

And what of the beautiful sculptures of Camille Claudel?

I remember my mother’s mouth. The taste inside of it. When I was young I was beset by eating disorders.

Once, they say I was ‘put on’ Prozac. This drug increases one’s appetite. I ate the skin off my knuckles.

Oh, how my mother wept.

But she fed me. She chewed my food into mush because I was afraid of solid foods. I could not come to terms with my own throat.

The documentary crew sometimes put make-up on my face. They say it is necessary.

Omissions are necessary.

My memory fails me every day. I confuse food names, yes. I mistook somebody for a saltshaker.

The crew’s intern said I was going the way of de Kooning. Willem de Kooning, what a guy. Truly, a wonderful artist.

I know more about Willem de Kooning and Leon Golub than I do about my own father and my own son.

Omissions are necessary, yes.

The crew is preparing to interview me about my son. I say I do not remember my son.

I say that my head is stuffed with pepper. I say I want to sleep. I tell them my wife’s in the clinker and that she could never forgive herself.

Omissions are necessary.

They are, yes, and I cannot forgive myself.

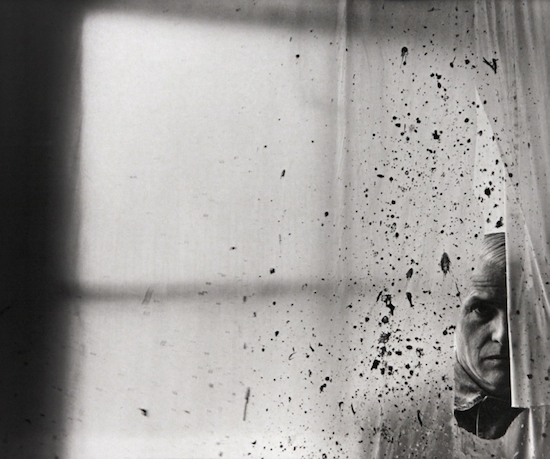

Work by Oliver Zarandi has recently been published in Hobart, Keep This Bag Away From Children, Electric Cereal and Human Parts. You can find him on Twitter here: @zarandi. (Photograph by Arnold Newman)