Over the course of this occasional series, and in spite of the fact that several of the records whose anniversaries we’re marking have been debuts, there’s been precious little sense of new beginnings. Snoop’s Doggystyle was a debut in name only: as the follow-up to The Chronic it was an album from an established team, released to sate the slavering anticipation of a huge audience already primed to expect most of what it contained. Even the last album we looked at – Nas’s Illmatic – as great and as impactful as it was (and remains), didn’t come entirely out of nowhere. Nas was already the chosen one, the golden child, the lyricist du jour: things were expected of him, and his LP delivered on the promise.

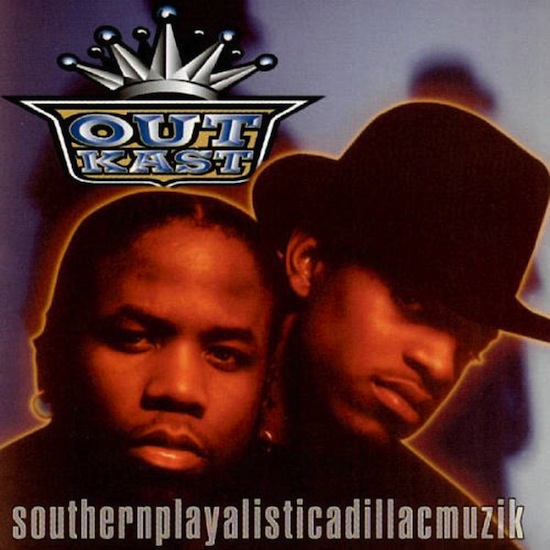

So Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik is something new for our immediate purposes here and now, because it was something new back then. Big Boi and Andre weren’t just hip hop unknowns (yes, they had guested on a TLC remix, but both assess their contributions as forgettable at best, and it wasn’t like that version of the track was a hit): they came from a city that wasn’t even on the rap map. By 1994, London had a far more illustrious track record than the Georgia capital: true, a couple of the music’s greats had chosen the city as their new home (Chuck D set up shop there; Erick Sermon chose Atlanta as his base of operations after EPMD split) and the Jack the Rapper convention had shown that there was a vibrant market for the music in the south. But those could be explained away as logistical choices rather than artistic ones. Atlanta was becoming a power centre for black music, but the hits coming out of the city by the time OutKast began work on their debut were, in the main, soul, not rap.

That would change, of course, and quickly: a year after OutKast’s debut, Goodie Mob’s Soul Food – and in particular the song ‘Dirty South’ – got people talking about this new gravitational force in rap, about Georgia at first, and eventually Louisiana and other neighbouring states, as being a hip hop talent-bed to rival NY or LA ("My associates and I named the south ‘Dirty’," Cee-Lo would recall on a later, solo recording). But, in 1994, this was all in the future. OutKast – with more than a smidgeon of help from a production team called Organized Noize and the emcees who were about to form Goodie Mob – would forge not just a career or a scene, but a piece of musical geopolitics.

And not only were OutKast a new band from a new part of the hip hop universe, they also had a completely new sound and style and musical approach. New for 1990s hip hop, anyway: the Sugar Hill label had a house band, and made this often loop-based music using live musicians, but as the genre reached its Golden Age zenith, samples ruled the roost. Most hip hop producers who used studio musicians did so only to re-play samples and thus avoid paying mechanical royalties: and in a sense, what the Sugar Hill house band did was pretty much the same. Whatever: by 1994, nobody in hip hop was making albums the way OutKast and the brilliant Organized Noize opted to make this record: writing new music, having it played by session and club musicians, and smothering it with a polysyllabic, tongue-twisting style of rap that, even on its own, would have been enough to mark the duo out as something different.

And yet, the antecedents to this out-of-the-blue release were pretty obvious, even if it didn’t dawn on some of us until years later. Which is where the links to some of the other records in this series first start to appear – and which may help explain how, in a way, the ground had sort of been prepared for such a different-sounding, different-location-hymning record. As I mentioned when writing about The Low End Theory, Andre had said a few years later that Tribe, De La Soul, Das EFX and Souls of Mischief were "some of the best hip hop groups ever." You can hear it all over their debut, particularly in Dre’s and Big’s verses on ‘Call Of Da Wild’ where the tongue-flip style of Das is in full effect.

It’s well known Andre and Big Boi were school friends, but that wasn’t where they met. Though they’d seen each other there, and had taken notice of a possible kindred spirit as they were both new to the school, the first conversation took place at the Lennox Square shopping centre, where Big had gone with his little brother.

"We didn’t have any money, no jobs or nothin’ at the time," Big Boi recalled in 2003, "so we was just window-shoppin’. Dre was in there, I remembered him from school, we started talking. We walked around a little bit and he was like, ‘Y’all wanna come back to my house?’ Cool. Caught the train back to his pop’s house. He was playin’ music – KMD’s ‘Peachfuzz’ was out at about that time; Tribe Called Quest ‘Bonita Applebum’; Poor Righteous Teachers; Ice Cube’s Kill At Will. And actually he was airbrushin’ – doin’ graffiti on clothes. People at school would give him jeans and T-shirts and want different designs. So while he was doin’ that we was just in there smokin’, talkin’. It was on a Saturday: I’ll never forget it. And on that night we went out, just rolled around and did nothing really – just talked."

The pair bonded over their differences from others around them. An idiosyncratic fashion sense was an important ingredient in them realising that they could not only be outcasts from the rest of their peer group, but take on OutKast as a creative identity – Big would get teased for wearing a tennis sweater without a shirt underneath ("Matter of fact, it was pink," he recalled. "It started out white but I dyed it. I caught hell that day at school") and Andre, even at this stage, was starting to show the individuality that would later see him feted as a global style icon.

But music was the key part of it. As Andre explained: "We liked all the hood music, from Geto Boys to 2 Live Crew to NWA; but there was something different that we both liked – Tribe, De La Soul – and at our high school, people weren’t really into that. Not in the south, you know? At that time, what was reigning supreme in the south and Atlanta was just bass booty-shake music: like 2 Live Crew and Miami bass. We loved that too, but at the same time we wanted to be a hip hop band: we wanted to do hip hop. As far as people considered emcees, it wasn’t really big in Atlanta. So we felt like we were different from what was going on in our city, and [were] inspired a lot by groups from up north and out west."

Tribe, in fact, played a vital if unwitting role in OutKast getting to make this record. Having decided that hip hop was something they wanted to make, the pair spent weeks rapping over the instrumentals found on the B-sides of their favourite singles. Among them, Tribe’s ‘Scenario’ and its remix reigned supreme, but not particularly because of the variety of different flows from Tribe and guests Leaders Of The New School that the vocal version boasted.

"Back then it wasn’t really about outdoing [Q-Tip and Busta Rhymes] or whatever," Andre explained. "We really just wanted to be up to par. Being from the south was already like a defect – you were already thought of as not being able to do it. But ‘Scenario’, and the ‘Scenario’ remix, those were some of the fonkiest beats ever. And the first time we met Rico [Wade] of Organized Noize, we had the ‘Scenario’ instrumental on and we just rapped damn near the whole song, non-stop. Big Gipp from Goodie Mob – it was his truck we were listening to it out of. We put it in his cassette. We didn’t know Gipp or Rico or none of them, but Rico knew people who did beats – Ray [Murray], and Sleepy Brown. He said, ‘Let me hear what you got,’ so we put in the ‘Scenario’ tape and started rhyming, non-stop, back-and-forth."

Wade had heard something special, and it had arrived in front of him at an opportune moment. Organized Noize, the production unit he had founded with Murray and Brown, were starting to get noticed. The Atlanta-based LaFace imprint, a joint venture with Clive Davis’s Arista run by Antonio "LA" Reid and Kenneth "Babyface" Edmonds, had shown some interest in the team – though Andre’s recollection is that, at least at first, the label wanted to sign Murray alone ("I guess he said, ‘No, I don’t want none o’ that if I can’t bring all my homeboys with me,’ so they kept the connection but they didn’t sign Ray"). Atlanta’s biggest musical export, TLC, were signed to the label; an Organized Noize remix of a single from their 1992 debut LP was in the offing. Some local rappers might add to the ON cachet – as long as they were any good.

"That day, after we rhymed, Rico saw something in us," Andre recalled. "At that time we’d both shaven off all our hair. We’d dyed our hair blonde one time: we were young and in high school, we were outcasts, you know? Rico saw that, and he said, ‘These guys can really rhyme. They don’t really rhyme like people from the south.’ So he told us to come over to his house, and that’s where the Dungeon is, in the basement."

The collection of emcees that would assemble at Wade’s basement in the coming months reads today as a who’s-who of Atlanta rap royalty. Back then, Cee-Lo Green hadn’t officially joined Big Gipp, T-Mo and Khujo to form Goodie Mob – he had been making beats with Andre and for a while during this early period he was the third member of OutKast. Sleepy Brown, who sings the Curtis Mayfield-tinged vocals on a string of releases from what became known as the Dungeon Family, starting with Southernplayalistic…, would make his own records; Cool Breeze and Killer Mike would get their turns in due course. First, everyone had to learn the ropes.

"Rico wasn’t really doin’ beats back then, he was more the talker – the business-type of person," Andre recalled. "Ray Murray was the beatmaker in Organized Noize. And he took us downstairs and played us tracks: I was amazed. It was some of the best music I’d ever heard. Up until that time, me and Cee-Lo would make tracks with two cassette players, where you keep looping it and stopping it on time. But what Ray played us sounded like real songs. It sounded like some real shit you could hear on the radio. I was amazed, and we just started making songs and writing. And from that day on we just started staying in the Dungeon."

The first fruits of Big and Andre’s subterranean labours were unlikely, and – they reckon – forgettable.

"They asked Organized Noize to do a remix of a TLC song," Andre remembers. "They did a beat, and without telling LaFace, they just put us on a record! The beat would break down and we did our little rap. I actually think it’s wack. It’s really wack! It’s one of the worst verses ever, but it was an opportunity."

The appraisal is harsh: the pair’s verses may lack the kind of individuality that would soon enough become their calling card, but that wasn’t really the point. In those few seconds you might not get to hear the two globe-conquering major artists Big and Dre would become, but you do get a glimpse of what they were at that time – two schoolboys hopped-up on New York lyricism, given an unexpected chance to hog the limelight, and jumping in with both feet. And, whatever they would later feel about their performance, it got them an album deal. Or, at least, it got them the audition that got them the showcase that didn’t get them the deal, yet still got them the deal.

"You’ve got to think that when LA of LaFace gets this remix, he’s like, ‘OK, who’s these guys rapping on my record?’," Andre said. "That was his first introduction: that’s the first time he hears OutKast. So we said we wanted to meet him, so we set up a meeting and we took these DAT tapes of beats we had down in the Dungeon. So we’re in LA’s office, and he was like, ‘OK, I wanna check y’all out.’ He says, ‘Hold on’. He gets on the intercom and he calls everybody – the whole staff of the company. I don’t know what floor it was – high up, though. And from marketing to the mail room, he brings them all in to the office. Then he says, ‘OK, go.’ We’re nervous as shit, we got everybody looking at us: Rico puts on this tape and we start rapping."

The response was good enough for Reid to get OutKast to present their songs to the label in a rehearsal room. "And they came in after the showcase, and he says, ‘Yeah, it’s alright man, but I don’t think I wanna sign these guys’," says Andre, continuing the tale. "We were feelin’ bad that night. But around town, word started to get around that we were doin’ our thing. Polygram wanted to check us out, so they set up a showcase for us. And then LA heard other companies were checking us out, and I guess he didn’t wanna miss the boat. So he was like, ‘OK fellas, I know what I’ll do. I’ll give OutKast a chance to do a song on a LaFace Christmas album."

That song was ‘Player’s Ball’, and it changed OutKast’s lives. Released as a single in November 1993, it went on to top a Billboard rap chart, and set the duo on the path they still are walking. Its success enabled them to make their debut album, and the song provided the pair, and Organized Noize, with a template they would stick to for the LP’s ten other full-length songs. A languid groove over which the rappers got plenty of space for their double- and triple-time flows, a sung chorus or hook giving an instant pop-friendly radio-readiness, and lyrics about dope dealing, hustling and being a bit of a G. Wait – what?

Strange as it is to note, for fans who first heard the band on ‘Rosa Parks’ or when the apologia ‘Ms Jackson’ was a hit in 2000 and for whom Outkast have always been about a certain higher level of consciousness, the lyrical content of the pair’s first record appears, to the less finely attuned ear, to be little more than a series of gangsta cliches set to mellifluous music. And, truth be told, there’s a curious irony involved in the duo deciding to call themselves OutKast because they felt so different (musically and as people), in them starting to make music because they were so inspired by cerebral wordsmiths like Tribe and De La, in them evidently putting so much store in individuality and creative integrity, and the fact that they chose to make a debut so self-consciously patterned on what was selling in hip hop at the time.

"The first record was basically a lot of pistol play and thug shit: curse words galore," Big Boi told me in ’03. "We were young – 16, 17: all we thought about was smokin’ and drinkin’, you know what I mean? We was not necessarily on some gangsta shit, but we was on some playa shit. We mind our business, we kicked it how we kicked it, and if you can get down, get down, and if not, lay down. It was rough, pimped-out and gangsta."

"The first album was street," agreed Andre, in his separate interview that day. "It was all about bein’ a young guy, protectin’ your own, all about bein’ a pimp and a playa, and just bein’ a fly guy. A lot of gunplay, a lot of smokin’, it was Southern lifestyle at the time. And I think a lot of that just came from the music that we were hearing, wanting to appeal to a certain crowd. Dogg Pound, Snoop, Geto Boys – those were the people that we loved, and we wanted to be in that crowd."

Hip hop, perhaps more so than any other genre, seems to pride itself on how closely the art is reckoned to mirror the artist’s life – and its audience seems to judge its artists by how small a deviation between the two they can maintain. Yet here we have a group that would become one of the art form’s biggest-selling and most revered institutions, freely admitting that a debut album made when they were still at school is all about a lifestyle they’d learned about from listening to other records. In songs like ‘Claimin’ True’ they’re talking less about something they lived, than a lifestyle they felt they needed to be seen to aspire towards. And it worked: at the 1995 Source Awards, they were voted best newcomers – a huge achievement for an act from neither of hip hop’s coastal power cities, and a decision which helped cement the idea that the entire focus of what the culture was all about had shifted away from the New York traditions of hard beats and incisive, occasionally politicised lyrics (Nas and Illmatic won nothing), and had lit upon the post-Chronic style of smooth beats and gangsta storytelling.

Was none of it real? Well, the bits about drug dealing may have been taken from the life – if they’d been a bit better at selling weed than they were at consuming it. "We started!" Andre chuckled, when asked whether the pair had done much drug dealing back in the early ’90s. "Me and Big Boi had a drug plan. We were gonna sell weed. But it didn’t work out. I don’t know how much we bought – maybe four ounces or something. Then we bagged it up into these little dimes [bags], and we were gonna peddle ’em. But we just ended up smoking it. Back then, I didn’t have a lot of worries because I was doin’ a lot of drugs and I was high all the time. I smoked a lot. A lot."

But there’s another way of interpreting OutKast’s debut that the reductive, "it’s a gangsta/player album" rendering – even if it’s underscored by the two men at the heart of the album’s creation – ignores at its peril. And that is that Southernplayalistic… is no more just a gangsta record than it’s just an exercise in fast flows. We can all bemoan hip hop’s 90s descent into cliche and self-parody, and assess this as the result of the artists scrambling to dumb down; but that presupposes that the audience was entirely stupid and self-destructive. There’s no way OutKast, Organized and Goodie Mob (who are well represented throughout the album, albeit miscredited as "Goody" on the sleeve) would have been able to achieve all they did on this record if it had been as two-dimensional and as thematically thin as this interpretation suggests. And, more or less wherever you look on an album which is, admittedly, heavily reliant on dealing and player archetypes and hype, there’s something deeper, less formulaic and far more compelling.

Sometimes the strength resides, first and foremost, in the sonics. ‘Ain’t No Thang’, even if the lyrics hadn’t been anywhere near as strong as they are or the performances of the verses had lacked something in technical execution, would have been a benchmark recording anyway. There are three key elements to the sound, each perfectly balanced to create a piece of music which, on its own, is almost strong enough to have supported the creation of a Dirty South scene. First is a rumblingly sinuous bass line, full of funk and portent, anchoring the track to a bedrock of soulful menace. Next is a recurring rasp of static, a scuffed-groove nod to the crunchy aesthetic of sample-based hip hop, a grit-on-the-needle crunch that says, "We may use musicians to play this stuff, we may write the music rather than lift riffs from elsewhere, but we know, understand and are a part of the style and sound that you know and love, so give us five minutes to allay your fears." And above it all is what sounds like an effects-laden guitar noise, perhaps an echo-drenched rasp of a plectrum along a wound string – or maybe it’s a keyboard setting marked "pterodactyl". Either way, this noise – like the alarm call of a strange bird – punctuates the track and gives it an unmistakable air of difference. It’s almost as if Organized wanted to announce to the listener that they were entering a strange and unfamiliar world, and we needed to tread carefully here, keep our wits about us, and keep watching out because here, possibly, there may be monsters.

But it’s in the lyrics where the idea that OutKast’s debut is a work of hacks trying to keep up with the Joneses completely falls apart. True, there’s plenty of banal content and ludicrous claims being made by schoolboys who were pretending to be Gs; but there’s also a ton of wit, insight and laser-focused intelligence here. Take Andre’s verse in ‘Claimin’ True’, where on the one hand he claims to have been "slangin’ quarter keys", which, in light of his 2003 admissions over the failed pot-selling scheme is revealed as stretching the truth more than just a tad, but on the other he writes with some empathy and bite about an economic system that leaves women with so few options to make ends meet that they sell their bodies.

Similarly, ‘Crumblin’ Erb’ devotes a fair chunk of its three verses (one and a half each from the duo) to brags about Big and Dre’s fictional prowess as weed dealers, but it also muses on the importance of the herb to their creative process, which at least feels a bit more like the truth. And in Andre’s opening stanza there’s something altogether deeper and more nuanced, as he essays, in a first-person vignette, how societal pressures and marketing muscle conspire to inculcate wants and needs in people who don’t have the means. It’s not an entirely original observation, and even at its most carefully crafted it can often come off like someone making excuses for people who’ve allowed themselves to be led by greed into making some obviously bad life choices: but there’s art here, and poetry ("Let me dig into your brain, folks fallin’ like rain"), which comes across as something rather more than the stoned ramblings of a drink- and weed-obsessed teenager. And then there’s the song’s chorus, its blend of lament for the death and destruction that gang crime has wrought with the hope that those involved in that life who are listening might wake up and realise that "there’s only so much time left in this crazy world". And it’s all prefaced by a spoken-word intro from Dungeon Family member Big Rube, who rounds up a few of the usual conspiracy-theory suspects but drops some insight into the brew as he explains that anyone who feels like they’re on the outside of the establishment will end up shunned, and that makes us all outcasts, in a way.

And best of all, at the heart of the album, there’s ‘Git Up, Git Out’ – at once the record’s spiritual and conceptual centrepiece, and a genuine, heartfelt, incisive undermining of all the stoner talk that surrounds it. The basic message is: don’t waste your life sitting around, smoking dope, wishing things were better – get out of bed and sort things out for yourself. It begins with Cee-Lo, in his first appearance on a record (weeks later he’d be singing the chorus to an Organized-produced TLC track: ‘Waterfalls’ remains one of the least-known-about entries on the big man’s CV), mining the kind of confessional and genuinely autobiographical seam he continues to quarry with Goodie Mob and in his solo and Gnarls Barkley records. And it ends with Dre delivering what feels like the one moment on the record where he really lets loose with what’s going on in his head and his heart, an acknowledgement of the directionlessness he felt bouncing between his separated parents and how he knows now, broke and without a high school diploma, that his mum was right when she told him to pull himself together.

The track seems to have been the key to what happened next. In the wake of the album’s success everything changed. On turning 18, both men received their first royalty and advance cheques, and bought themselves new cars. They’d never told any of their high school friends that they were making an LP, figuring that enough people talked that shit without ever being able to back it up that no-one would take any notice anyway, so it was better to let them find out when the videos hit MTV; but their growing nationwide rep meant touring, which exposed the pair to other people and other lives. For Andre the penny dropped: he gave up dope and drink, got his life together, became a vegan, and never looked back. For Big Boi, who in later years would always seem the more street, more grounded of the two, the track made him realise the potential he and his schoolfriend had tapped in to, and revealed the responsibilities that now were theirs.

"I first discovered how deeply the microphone can affect someone’s life when we did the song ‘Git Up, Git Out’," he told me 11 years ago. "We were on tour and not just one, two, three, four, five cities, but everywhere we go there was some college student or high school student that came up to us and was like, ‘Man, thank y’all for makin’ that song, I got my diploma, I went to college and got my degree, I did something with my life instead of just sittin’ around smokin’ and drinkin’ all day’. And that shit is big time to me. I’m like, ‘Man, you changed somebody’s life! Woah.’ And from that point forward it’s like, when I grab the microphone… I mean, you can have fun, you can party, you can do all of that, but why not drop a little something in there to make the listener think? Like, if you can touch somebody’s life, why not say something? Life ain’t just about partying all the time: you can do that, and it’s all fine and dandy – we do all that. But at the same time, when you have such a forum, speaking to the whole fuckin’ world, why not drop a little science on ’em? Let ’em know something! Let ’em know you’re thinking about something. Let ’em know you’re bigger than just ‘rap music’ or ‘hip hop music’ or music in general: let ’em know you’re a person, and the shit that go on in the world affects your life."