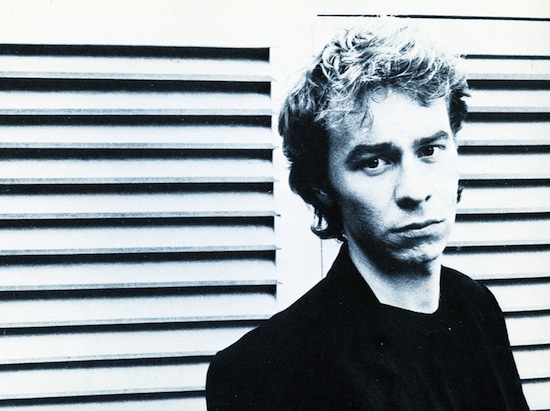

Matt Johnson portrait by Nicola Tyson

It’s funny how your childhood and young adulthood falls away. Some of the songs and albums that meant so much at the time, played ‘til the tape snapped or your dad hid the record, can seem gauche and irritating at best when revisited. Other tunes are so played out that, despite their obvious brilliance, you’d sooner duck out of the room or turn the radio off than sit through them one more time. At the other end of the scale some music has been so thoroughly forgotten about that it can trigger a rich flood of Proustian recall on hearing it unexpectedly on the radio or in a bar – but often it’s a one-time deal, try and repeat it and you can find those emotions have dispersed for good like pollen on a breeze.

I actually listen to a fair amount of music that came out during my early to mid teens for work reasons and derive a lot pleasure from most of it. I’m still a fan of most of the bands and artists that I loved while a schoolboy bar one or two notable cases. (Sorry Dire Straits! Sorry Thompson Twins!) But I’d be lying if I said that there were more than a handful of songs that still have a similar emotional/what the fuck-impact on me now as they did when I first heard them. There’s a hardcore of tracks which shift in ranking but include Joy Division ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’; Motorhead ‘Ace Of Spades’; Donna Summer ‘I Feel Love’; OMD ‘Joan Of Arc’; Tubeway Army ‘Are “Friends” Electric?’; Soft Cell ‘Say Hello, Wave Goodbye’; Iron Maiden ‘Phantom Of The Opera’; The Smiths ‘How Soon Is Now?’ which always hit me hard – emotionally and physically; and always nestling near the top of the list is the album version of ‘Uncertain Smile’ by The The.

Soul Mining, The The’s debut album (not including the retrospective prequel Burning Blue Soul), has always been a cornerstone of my record collection and therefore never thdat far from the record deck so it’s not like I’ve had a chance to forget just how good this song is. Opening with a wonky, homemade tape loop of African sounding percussion, it has a bittersweet but breezy pop groove that is the very definition of insistent, chiming guitars and gorgeous synthetic strings. Matt Johnson – who is for all intents and purposes The The – delivers the song in such an easy manner it almost belies the shattering universal impact of the lyrics and that’s all before you get Jools Holland’s simply beautiful piano solo. It really is a perfect song, no pun intended.

And it’s in good company.

Soul Mining to me is one of the all-time greats. I listen to it in the same way that some others listen to Revolver or Pet Sounds. ‘I’ve Been Waitin’ for Tomorrow (All Of My Life)’ featuring Zeke Manyika’s punishing drumming and Thomas Leer’s exploratory synth work is like one of Can’s ethnological forgeries or Byrne And Eno’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts as applied to a blueprint for an industrial pop dance hybrid that was never to be realised. ‘This Is The Day’ is a perfect slice of pop melancholia while ‘That Sinking Feeling’ and ‘The Twilight Hour’ are two of the songs that earned The The a justifiable genre tag: “existential blues”. The title track is a soulful slice of downcast Afro synth beauty while ‘Giant’ is a monstrous banger of industrial rhythms, proto-techno bass and ritual chanting. And Johnson staggers through the terrain of the album like a new face in Hell; as if a feverish stranger introduced to his own inner topography for the first time, anguished at what he’s found. He would go on to be a great political songwriter, with the emphasis on the personal as political. However to go down this route, first he had to get to know himself, and Soul Mining is the exquisite result of this exploration. But above all else Soul Mining is an immensely enjoyable album to listen to; romantic, exciting, cinematic, unique.

Even by the time this album came out in 1983 it was clear that it would be impossible to categorize The The, something that only became more pronounced with the passing years. It would be daft to say this fact has hurt Johnson to any great extent – several of his albums have sold very well indeed – but there has never been any genre or revival scene for people to hitch his wagon to. Because of this, paradoxically, in some respects The The still feel like a cult band – albeit one that operated from well within the mainstream.

It was my pleasure to spend three hours round at Matt Johnson’s London flat recently. (I should say that his space is exactly how you would imagine it to be, piled to the ceiling with interesting books, a bracingly expensive vintage stereo system with wood framed Tannoy speakers that could easily be converted for the purpose of kenneling St Bernard dogs. Piles of avant garde and left field CDs and vinyl on the floor. Heavy wooden blinds shuttered against the blazing sunshine outside. Apocalypse Now! ceiling fans…) I talked to him about the reissue, the chance of him reviving The The, as well as his plans for Spirit, Pornography Of Despair and Infected.

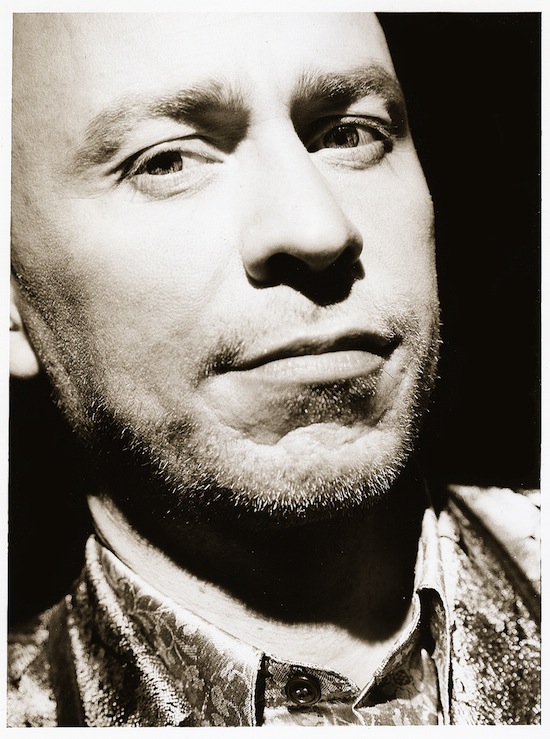

Photograph by Alessandra Sartore

I was listening to the reissue of Soul Mining today and something struck me about this album that has never occurred to me before. I think it’s pretty odd that someone who was a teenager or in his early twenties was writing these songs. I’d find it easier to imagine someone of your age now writing some of these songs. They were very emotionally mature, quite worldly. Did you have an old head on young shoulders perhaps?

Matt Johnson: I did go through a very intense period between leaving school and recording Soul Mining… because my mum wouldn’t let me have a moped [laughs]. I went through a very lonely and introspective period, probably for about 18 months to two years. I almost slipped into this [laughs] parallel universe. I liked school, I had a good time and was very outgoing there. I had my little band from the age of 11 and I enjoyed myself. But then suddenly my drummer got a Yamaha FS1E, they were mopeds that looked like motorbikes and all the kids had them. And I think a local kid had a bad accident riding one and my mum said, ‘You’re not having one.’ Which was fair enough. But that led to this period where I was spending a lot of time in my bedroom with my tape recorders and going for long walks by myself. Reading. That was what I’d call an emotional hot house experience. That period, really, really changed me. It deepened me. I started being able to see things I hadn’t previously been able to see and hearing things I previously hadn’t been able to hear. I started sensing things that I hadn’t realised were there before. And this tremendous infusion of energy had to find an outlet somewhere. Having been in bands since I was 11 making music by myself didn’t seem that big a deal. I saved up and bought an AKAI. Before that I was using the family’s reel to reel cassette player to do a basic form of over-dubbing. It meant I didn’t have to have a band and I could express all of these new feelings and sensations that I was having. And I needed an outlet, otherwise I would have gone mental. It was a very difficult time then but now I can look back and say what a fantastic period it was.

Another thing that struck me today is your lyrics and delivery, without being in any way parodic or revivalist, are kind of analogous to the blues. I mean, you didn’t sound like Leadbelly or whatever but in a way it was weird how this young white guy could be singing these very world weary, crestfallen, heartbroken songs. When you were writing songs like ‘This Is The Day’ were you in any way influenced by any of these amazing performers that you’d been lucky enough to see at your parents’ pub [The Two Puddings, Stratford, East London], like Howling Wolf?

MJ: No. But I do like the blues. Actually, I suppose the opening line to ‘This Is The Day’ is an ironic reference to the blues because it’s an inversion of the old, "Woke up this morning…" line but I don’t think I even realised that until years later because I was self taught. In fact it wasn’t until years later that a French journalist said to me, "Mr Johnson, why are all of your songs in minor keys?" And I went back to check and it turned out most of them were, or at least had some kind of minor key element. It’s hard to pinpoint influences. I mean, there are people now who go out and blatantly steal and I do hear artists now where I think, ‘Well, you’ve just listened to that and ripped it off wholesale.’ And years ago that is something that you would have been embarrassed to have done. You felt that your influences should percolate through you and you would listen to music voraciously but only in order to make your own statement. Taking someone’s style or sound wholesale, I just wouldn’t have done that; I wouldn’t have wanted to do that. The influences were so disparate really. The Beatles in particular, with The Beatles being an album I listened to when growing up and carried on listening to it into adulthood. Just the sheer variety of it was great even though the band were kind of at their lowest ebb. It was sort of like four solo albums in one really. But it was that diversity that was inspiring to me. And there’s a strong blues influence on that record. So the blues influence on me, apart from what was coming up through the pub floorboards, in terms of intense exposure would have been through white guys like John Lennon – the blues going via them into me. I do take that as a compliment though because I love the blues and it does resonate with me. Just listen to ‘Smoke Stack Lightning’ for example. But I’ve never tried to replicate it.

You seemed to jump around between record labels a lot at the start of your career…

MJ: I was with 4AD first and I was happy there. Ivo is a lovely chap.

4AD would have been an ideal label for you for the long run maybe…

MJ: Looking back yeah. But it was a financial decision mainly. I was on the dole at the time. I had no money, I was living in a bedsit in Highbury and Burning Blue Soul cost £1,800 to make. I had no advance. There were no royalties for a long time and I was still signing on. The way that Ivo’s deals tended to work was… well, not exactly on a handshake because there were contracts… but project by project. So it wasn’t like there was a long term contract. But at the parallel time I’d gotten involved with Some Bizzare and a chap called Stevo… who you’ve probably heard of… yeah… [slowly arches one eyebrow to an impressive height] Hmmmmmm… I’ve not seen him for a quarter of a century so I have no idea what he’s up to now. There was a period of time however when he did create an amazing record label. For a three year period, in the early to mid 80s it was the best label in the country. And then for some reason he sabotaged the whole thing and alienated everyone he ever worked with but that’s another story. But during that initial period of time there was a huge sense of expectation and creativity. Obviously they’d already had huge success with Soft Cell. I’d already done a single with him and a single with 4AD as well, so I was kind of between them. He said, "Look, why don’t you do another demo of ‘Cold Spell Ahead’ [the song that would become ‘Uncertain Smile’] to try and turn it into a single?" So I did this other demo and London Records loved it. He did what I refer to as a Tin Pan Alley sleight of hand deal. He got them to pay for me to go to New York, which was an expensive affair with a good studio and nice hotel. And he got them to do this without anything in writing. I came back, everyone was blown away by how great it sounded…

Tell me about the trip, because this is pertinent to the box set which contains these two versions… the New York remixes of ‘Perfect’ and ‘Uncertain Smile’ which are both amazing. And you were what… a 20-year-old? Had you been to New York before?

MJ: No, that was my first trip.

And how to put this… you’ve always had a love/hate relationship with America but presumably more of a love relationship at this point?

MJ: Well, my hate relationship is with the corporate oligarchy that own and control America and her foreign policy. But when I got off the plane in New York for the first time, suddenly it was like, "My God, I’m home. This is where I should be." And I did end up living there for several years. Downtown Manhattan is where I feel my spiritual home is. And Mike [Thorne, session producer] was brilliant, he took me around a lot and introduced me to a lot of people. So it all seemed really natural that I’d go with London Records but then things didn’t go according to plan because then CBS heard me and they wanted to sign me. And to be honest with you, I didn’t really like London Records. I didn’t find them that friendly. They were seen as more of a British pop label. CBS, that to me was more like Manchester United coming in to sign me. Suddenly it was Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Johnny Cash, that’s where I wanted to be. So I was delighted to be honest. I got friendly with a lawyer from CBS, a man called John Kennedy, who later became my lawyer and a friend. He lived in Highbury and he would often give me a lift and he loved my stuff. So I thought, ‘My God if the lawyer of CBS is this vibed up and friendly… even the A&R people at London were a bit unfriendly. But the truth of the matter is, was it was a sleight of hand that Stevo pulled on them and it wasn’t a good thing to do.

Were you at the infamous signing between The The and CBS with Maurice Oberstein and Stevo sitting on top of a Lion in Trafalgar Square?

MJ: No. He was a legendary figure Maurice. Very strange man as well. He always had this dog called Charlie with him and he had this odd hormonal thing with his voice which meant it was constantly going up and down by two octaves. He would go, "What do you think Charlie? Charlie don’t like it." Or, "Charlie really likes this." He was a complete crazy character Maurice. I liked him. A good guy. I didn’t go to the signing probably because I was embarrassed by the whole thing. I wouldn’t have wanted to sit on a lion myself. I thought I’d let Stevo and Maurice do that.

So at this point you had a couple of songs from the first New York session and a lot of unreleased work but you decided to start Soul Mining from scratch?

MJ: Yeah, at this point I had another album Pornography Of Despair which I was working on in my own time. I was signed on the strength of ‘Uncertain Smile’ [from the New York session] which was the most commercial thing that I’d ever done… in fact it was the most commercial thing that I’d probably ever do. So when they heard everything else I’d recorded up to that point they probably thought, "What the fuck is this?" So they asked me if I’d go into the studio and make these songs more commercial, which I did but I was never convinced about the results. So then I invested in a Portastudio and some Tannoy speakers, got some other bits and pieces, bought a Fender Strat, a Suzuki Omnichord, a couple of little synths, a drum machine – a Roland TR-606 – and set about writing Soul Mining. And I can remember lying on the floor of my flat writing the album. I always used to lie on the floor to write but I don’t any more because my knees ache. But I’d always be on the floor with loads of pens and pencils, always doing loads and loads of writing. Annoying the neighbours by playing the music. I remember it very clearly. Recording versions of some of those songs like ‘Giant’ and ‘Waiting For Tomorrow’ I guess I was using what would now be called a loop method of working but of course we didn’t have computers then so it was just made by me recording a part for as long as I could. I was playing the same parts for ten minutes because I didn’t have a sequencer and was using myself as a sequencer. I never fell out with Mike Thorne but Stevo did so we decided to change direction and then went with Paul Hardiman who had already worked with Wire. I met Paul and liked him instantly. Initially we did a remix on ‘Perfect’ which I was happy with. I liked Mike’s sound but it was softer. Paul’s had a bit more balls to it. A bit more edge. And also I wanted to co-produce. I had a clear idea of what I wanted but I like to co-produce because I like having a foil in the shape of a good engineer. Paul was a first rate engineer and a great guy. His influence is on the album and he had a great sense of clarity.

It must have been exciting this period because through Some Bizzare you were meeting all these other really vital artists, like Peter Christopherson, Marc Almond and Dave Ball.

MJ: There was a period where it was like a big family. We hung out together, we went to shows together. There was not only myself and Soft Cell but Psychic TV, Cabaret Voltaire, Jim Thirlwell, Einsturzende Neubauten, Test Department, Swans… and everybody got along. We complimented each other but did different things. And often we’d turn up as a group, mob handed. There would be these insane parties round at Stevo’s house either all night or all weekend long. It was a real… [laughs]… well you can imagine what it was like. The only problem was that it was very, very druggy and after a period of time the paranoia started to set in. There weren’t really any problem between the bands but there were with the main man: Stevo. He was the one who caused the problems – for himself and everyone else. The bands got along well. Marc was a lovely guy, very supportive to me and I still see him occasionally. I don’t have a bad word to say about any of the acts on Some Bizzare. We all listened to each other’s records when they came out. Stevo would crank the stereo up loud and was enthused by everything that was going on but then it all got screwed up. The drugs. The paranoia… whatever. I got out of there after Infected.

How did you assemble the team for Soul Mining because you worked with some great musicians didn’t you?

MJ: Yeah, there’s a combination of mates, session musicians and known musicians who I didn’t know personally but who had been recommended. So in the former category there was Jim [Thirlwell], Zeke [Manyika] and Thomas [Leer]. I did this show at the Marquee, with what I used to call a The The supergroup. These were great events really. Mal [Cabaret Voltaire] would have been there and Marc Almond and a bunch of others, including Thomas, Zeke and Jim. So I chose to bring those three into the recording. But Zeke… [laughs] I saw him the other week to interview him for Radio Cineola. I’m doing a special on The Garden [Johnson’s East London studio, built by John Foxx] and Soul Mining and I reminded him about this. Of course there was no email then and no mobile phones and Zeke is someone who operates by his own schedule. He turned up three days late for the session. But it was worth the wait because he was absolutely brilliant. ‘Waiting For Tomorrow’ that absolutely vicious drum sound. His contributions to ‘Giant’ were amazing as well. Zeke was a close friend and a drinking buddy at that stage as well and someone that I loved hanging out with, a very creative guy. Jim, again, someone who I’m very good friends with, made a cameo appearance on the album as Frank Want. Now at the time I don’t think I’d thought what I wanted him to do; I just wanted him to be on the album because he was someone important in my life and we had very limited instruments in the studio. So he just went into the kitchen and came back with this assortment of trays and pots and pans and laid them out. We were like, "What the Hell is he up to?" But he got Paul to record him over and over again and he built up this amazing syncopated rhythm just from that. He’s very unorthodox Jim. He’s got a wonderful mind. And Thomas I wanted involved because he’d been a really big influence on me. Particularly that single of his ‘Private Plane’, which was the product of just one guy on his own in his bedroom. I mean, it’s really common now, you have one man bands all over the place but it was very unusual in those days. It was when I heard his stuff for the first time that a real lightbulb went on over my head and I thought, "My God, I don’t need a band, I can just do it myself."

I wanted to ask you about Jools Holland’s involvement. There are a lot of things to commend Soul Mining but his work on ‘Uncertain Smile’ is utterly amazing. To this day it makes the hairs on my arms stand on end. It really is one of the greatest piano solos from all popular music, period.

MJ: Yeah, it is. Absolutely. And I’ve not seen Jools for years but the last time I saw him he said he gets asked more about that than anything else he’s done. It was astonishing to watch. He did it in one take, with just one little drop in at the end. Me and Hardiman were just… Well, you know when you’ve got something. And just how cool he was as well. Well, not literally, it was a sweltering Summer’s day and he turned up in full leathers on his vintage Norton bike so he wasn’t cool, he was sweltering somewhat. But he was very humble, very low key, very nice person. It was recorded on a nice piano and I still own it. It’s a Yamaha C3 baby grand and it was in a really good live room. Someone asked me why I chose to put a piano solo on that song and it was simply because we had such a nice sounding piano in such a nice sounding room. It had to happen. It was the cherry on the cake for the album, in a way. Until recently I hadn’t heard the album for a long time, I don’t own my records and I never listen to them. So for this I decided that I didn’t even want to hear it until we were in Abbey Road to remaster, so I could listen to it straight off the tape. And hearing that solo was like, "Woah." Just the way that he builds it and develops its to one crescendo to another after another. It’s beautiful.

And it’s all of these inclusions that make it what it is. There is industrial on the album but it’s not an industrial record. There are pop elements on the album but it’s not a pop record and so on and so forth. Do you feel that over the years this has been a double edged sword for you?

MJ: I’m pleased that my stuff isn’t categorisable but I do have problems if I’m talking to someone that I don’t know and they want me to tell them what kind of music I do. One great description that I did like – although I can’t remember where it came from – was existential blues but then that makes people think what I do is more blues-like than it is. I like to be away from everyone else, to be a bit of an outsider. It does cause problems because we live in the kind of society where people like to categorize things, whether it’s a TV show, a book, a film, even if it’s just a way of explaining to people what it’s like. If you were telling me about a film, I’d want you to categorise it for me. I’d ask you what it was like. It’s probably human nature to do that. But I’ve always felt very, very uncomfortable when people tried to put me into a category. And I always liked the fact that all of my albums sound different. And within the albums themselves they’re very varied as well. But I guess if you look at my career you could say that I’ve made all the wrong career choices for all the right reasons. Even including the band name – but who could have predicted iTunes and Google! But that’s just the way it is. I’ve made so many decisions to turn stuff down that would have helped me; TV appearances, festivals. And in the same way I made the decision to not be categorisable but that was down to me and it means my career has been a very strange one and that I don’t really fit in anywhere. But as far as it being a double edged sword, I’m happy that I don’t fit in anywhere. Ultimately, if I do ever come back and start doing proper albums again, or whatever… or when my career is properly closed forever, I’d still like it to be impossible to categorise my music. I think that’s great. I’d be very proud of that actually.

What about when Soul Mining came out? How did it go down?

MJ: I haven’t read any reviews since the album came out and I don’t like reading reviews. I’m not that comfortable with it. But it was well received. Infected was a bigger deal but Soul Mining made quite a splash. Infected was a magazine front cover kind of thing. But yeah, it got good reviews. I think the only album of mine that got mixed reviews was Mind Bomb and that was because it was a very political album. People were like, "Ugh, what’s he writing about Islamic fundamentalism for? What’s that all about?" Now, the same people are saying to me, "Ah, I see what you’re saying now…" But also it was my turn to be the whipping boy. You know how things are in this country. You have to take your punishment. If you take the good then you have to take the bad is well. And I’m OK with that. But Soul Mining was received very well. I’d given up playing live. I didn’t think I could recreate the album live. It wasn’t an album for a bass, guitar and drums, traditional rock four piece and this was before samplers became affordable. I didn’t think it would be possible to do. Now it would be easy but then I couldn’t afford to have 12 people on stage, so instead I did a huge amount of press. I did hundreds of interviews and that probably would have contributed to its success.

Your graphic and design aesthetic really came together during this period didn’t it?

MJ: Yes.

Do you want to tell me about your brother Andrew and Fiona Skinner and what influence they had?

MJ: Yes. My brother Andrew always had a very big influence on me when I was growing up. He was two and a half years older than me. And his big thing was drawing. And we’d talked about working together when we were working in the cellar of one of dad’s pubs, The Crown. So we’d be down there smoking cigarettes and stealing beers. He was a big inspiration to me. He was one of the first punks. He was there when the Sex Pistols played the 100 Club. I didn’t like punk, maybe because it was his thing but he was always bringing this influence back to me. He got me into the late 70s No Wave/New Wave punk scene. Patti Smith, Television, Talking Heads. He turned me onto a lot of stuff. On Burning Blue Soul there’s a drawing of me that he did but when we came to do this album Epic CBS were like, "You have to have a photo of you on the album and you have to go on tour." But I must have been seen as a real pain in the ass because I said, "Nope, sorry, not going to do it." Then Andrew did a series of illustrations for it, starting with ‘Uncertain Smile’.

Tell me about the sleeve.

MJ: The European sleeve to the album is odd. It was actually a painting Andrew had done of one of Fela Kuti’s wives with a joint in her mouth. I saw it in his studio, and I just loved it. It fitted in with ‘Giant’, you know that African element, and the warmth and the colours.

Fiona was my girlfriend at the time and we’d recently got together. We’d fallen in love. She was a very big part of my life during the making of Soul Mining and she was a graphic designer for Thames Television at the time. She created a typeface. In fact if you look up there [points to framed picture on flat wall], you can see the alphabet that she created, she gave me that as a present. She created a whole unique alphabet by hand.

You had some problems with the tracklisting didn’t you?

MJ: Behind my back this cheerful avuncular guy who worked in A&R stuck ‘Perfect’ on the end of the album but it was never supposed to be on there. I was livid when I found out about it. He just said, "I thought it would be more value." But I was so angry that he would do that. I fought and fought and fought to get it taken off and eventually in 2002 I got it taken off and then I got loads of complaints from the American audiences saying, "What the Hell has happened to the last track?" And I had to explain that it wasn’t supposed to be there in the first place.

Were you unhappy regarding the release of Burning Blue Soul under your own name initially?

MJ: It wasn’t that I was unhappy. At that time I had so much energy and was doing so many different things. I was in my late teens, I was up to all sorts of different collaborations. And The The was still a collaboration between myself and Keith [Laws] and possibly Tom [Johnston] and Peter [Ashworth] were on the periphery at the time. And then Ivo from 4AD offered me a chance to do a solo thing. I was starting to play all the instruments myself then as well but because The The was still sort of a band it seemed sort of sensible to put my solo album out under my own name. But in retrospect yeah, because it was the first The The album really. I think on ‘Cold Spell Ahead’ I played all the instruments as well and that’s what it was becoming. So that’s why I went back in time and corrected it – even though Ivo didn’t want me to. He thought everyone would presume that he was going back and cashing in but it wasn’t him it was me who wanted to change it so they would all be racked together because prior to that they were kept separately. But I said, "It’s part of a family, it should be with its siblings."

It feels like Burning Blue Soul was appreciated by a lot of musicians but overlooked by the press…

MJ: I think it got some decent reviews… I was an unknown psychedelic teenager. I don’t think people knew how to do deal with it really. People didn’t really know where I was coming from. And where I was coming from was that I had been a studio experimenter as a teenager and been learning about techniques such as tape looping, tape flanging… there was a wonderful book by a guy called Terrence Dwyer [Composing With Tape Recorders: Musique Concrete For Beginners] about tape manipulation and musique concrete. So I was learning all that stuff, creating all of these fantastic percussion loops. So there was that on the one hand also combined with the fact that I had very little equipment back in those days. I had a Big Muff, an Electro-Harmonix device, a couple of reverb and echo boxes… I was quite influenced in those days by the early Pink Floyd/Syd Barrett guitar sound as well as the guitar work of Michael Karoli of Can. The other thing was, being quite young and shy I tended to drench my vocals in effects because I was singing very confessional stuff – stuff that was very close to my heart – so I put a lot of effects on it. At the time it came out of nowhere and didn’t really fit in anywhere.

In temporal terms maybe it was a year too early. But what about in spatial terms? It’s stupid playing the what if game but what if you’d grown up in Liverpool? I think the album would have been more accepted there because there was a stronger psychedelic scene there.

MJ: Yes, you’re right. If I’d have come from Sheffield or Liverpool I might have been popular. But I’m pleased things went the way they did because I’ve always liked to be by myself. I have never particularly wanted to be part of a group or movement. I’m very much someone who likes to be an outsider and independent. But you’re right in terms of acceptance and if I’d come from Liverpool at the same time as Teardrop Explodes, Wah! Heat, Echo And The Bunnymen I would have been more easily accepted.

Now people just coming to The The now could be forgiven for thinking that there was a huge stylistic leap between Burning Blue Soul and Soul Mining but that isn’t taking into account the fact that there was some material which didn’t get a full release.

MJ: Yeah. Spirits and Pornography Of Despair. One track from Pornography Of Despair called ‘What Stanley Saw’, did come out on a Cherry Red compilation called Perspectives And Distortion which is a good compilation and had a lot of interesting people on it like Lemon Kittens, Thomas Leer, Kevin Coyne… The title of that compilation Perspectives And Distortion was taken from another track from Spirits which in turn had come from a painting by my brother Andrew. This Spirit material was a bit rougher than that on Burning Blue Soul, there was a lot of guitar and keyboards; a lot of analogue distortion which I achieved by overdriving the channels. And then after Burning Blue Soul there was Pornography Of Despair, which was a richer sounding album, more song based but with some of the same loop elements and musique concrete. Around about that time there was a lot going on, so I was with 4AD then I met Stevo and of course there was a major label in the picture. And some of those tracks from Pornography Of Despair came out on the original cassette for Soul Mining. But I was never happy with it really. It was neither one thing or the other. It wasn’t what Pornography Of Despair could have been or should have been: it was a progression from Burning Blue Soul but it wasn’t as clean and as accomplished as Soul Mining so I rewrote some material. ‘Perfect’ was a hang over from Pornography Of Despair and that used to be called ‘Screw Up Your Feelings’. So I then wrote new material for Soul Mining.

Are you engaged in a long term project to actually release a definitive version of Pornography Of Despair?

MJ: Yeah, I am. In fact I’ve got a load of the tapes in the flat that need baking. I’ve been recommended something called a Dried Fruit Dehydrator that’s supposed to be more effective than the standard equipment. You bake tapes at a low temperature in a convection oven for 24 to 48 hours. These are non-standard solutions to a very new problem. The key thing is to digitize as soon as you’ve got them ready. I’ve got to get my old AKAI and REVOXes serviced and ready to go. I’ve got hundreds of tapes and most of them aren’t marked. What was I thinking? What an idiot. I’m the only person who can do it because I’m the only one who knows what to look for. That’s a process that I’m looking forward to it but it’s so time consuming. The plan is to do a box set. My first actual album was actually a cassette called See Without Being Seen and I do know where that is but it’s so rough. That will be one of those things that I put out without even advertising, purely for the hardcore followers. I was about 16 when I did that album. Pornography Of Despair will be fine. That will sound better than Burning Blue Soul. Spirits I think will sound pretty decent but I have to make sure it sounds good and I’d like to put it out as a nice set with photographs and the history.

Photograph by Johanna Saint Michaels

So tell me about the reissue. I’m a sucker for a good box set and this is such a thing.

MJ: Well, the idea to do it as a box came from my most recent manager Cally who manages the Nick Drake estate and works with Bill Drummond. He represented me for about 12 or 13 years even though we’ve recently changed our relationship. He was responsible for the Nick Drake box sets and you’ll see the ReDISCovered logo on it, which is Cally’s thing. He went up and had the meeting with Sony. I hadn’t had any dealings with them since 2002 when I last had the tapes remastered by Howie Weinberg. Now I love Howie, he’s an old margarita drinking buddy of mine from New York and he’s a great masterer but he does love the compression… you’ve heard of the loudness wars right? Well, I’ve been guilty of that myself. I do like compression and would crank it up a little bit and I probably went over the top with that at the time because that’s how I was feeling at the time and I was living over there. Anyway, the idea with this one is more of a purist’s vision. And that’s why the tracks from the cassette aren’t on here. I wanted to go the purist route. This is Soul Mining complete without other stuff tacked on to it. So we went into Abbey Road to bake the tapes and I said to Alex [Wharton] who was mastering, "I don’t think I want to use that much compression if any, I want to hear how it actually sounds." We put it through the old EMI TG series mastering desk. And as we were listening to the tapes, he said, "This is fantastic. The tapes sound like they’re only a week old." And all we did was a little bit of EQ round about 17, 18, 19k. A couple of dbs here or there. Just a small amount. It was interesting to me. As I said, I hadn’t heard it for years and it blew me away. I was really proud of it. We did work bloody hard on that record. I like good craftsmanship. I like stuff that is built well and built to last. The dream is to make records that will be listened to years from now. Whether you achieve it or not is something else but that’s the dream. I love it when people write and tell me what it’s meant to them. That’s what it’s for. That’s the vindication.

I feel almost churlish for asking but why was it a calendar year late?

MJ: It was just because of practicalities. We didn’t want to rush to hit the Christmas thing. We looked at my schedule, Sony’s schedule, Cally’s schedule, and this was the only time that everything fitted in.

Can you talk me through Dub From Disc – it sounds a bit bonkers.

MJ: Dub From Disc, we take the original acetates and we record them. So when you get a digital file it’s not just a digital file but it’s gone through an analogue form. The record player has to have some kind of historical significance. So in the case of Nick Drake it’s through the family’s gramophone. In my case it’s through my old TD-147 Thorens which was brought out of storage and restored.

And that’s what you’re hearing when you get the download?

MJ: Yes, you’re hearing this record deck.

I guess the million dollar question is will you do Infected?

MJ: You might say that but I couldn’t possibly comment. [laughs] We are talking about possibly doing it and it won’t necessarily be a 30th anniversary box if we do it. There’s a strong possibility it will happen.

Are there any plans to revive The The or do any other new musical projects?

MJ: Well [my label] Cineola is for my soundtracks, broadcasts, poetry but that is a very distinctive thing. If I was to do songs with vocals and lyrics that would be through The The. And I do start to get a tingling when I think about it… especially with all the geopolitical stuff going on at the moment. It’s what I’m interested in above and beyond national politics and have been for decades. It’s what I read about every night. So the question is how do I distil these ideas about the enemies behind the enemies, talk about the people who are really pulling the strings. How can I distil all this into a really effective song form because that’s what I’d really like to do. And the key thing for me now is how can I then focus all this information into really good song form and can I do it? Because I don’t want to be preaching at all. I also think it’s good to step away because there’s a tidal wave of music and I don’t want to be just part of this tidal wave. And I think if you’ve got nothing to say or if you’re not ready to say what you want to say then it’s good to keep your mouth shut, step away and let other people get on with it. And if the time comes that I do want to put out a new The The record and go out on tour again I will want to give it 100% and be full of passion rather than going out there to pay off an old tax debt or something. And then at least people would know that even if they didn’t like it, at least I was there for the right reasons. And that’s the important thing for me to be doing it for the right reasons and doing it full of heart and passion.

Until now, have you really only done one interview in the last decade?

MJ: Yeah, well I kind of retired from music in 2002. I didn’t make any announcements but the last show I did was in 2002 at David Bowie’s Meltdown Festival with Jim. At that stage I’d really fallen out of love with the music industry. This was the time when everything was disintegrating in the music industry. It was a horrible time. And I’d always been considered an album artist but that suddenly changed to me being asked for hit singles. I felt like I didn’t fit into this world any more. And I’d been so tangled up in bad deals – terrible publishing, dodgy old management deals from prior to that. And I just thought that if you are a medium sized band like The The, you’re really in a difficult position. Because the very big bands, they sell millions and millions of albums, they very quickly recoup, the renegotiate their contracts and very quickly get reversion, so they’re in a very strong position. If you’re in a small band you limp along for a while then you break up and that’s it. But if you’re in a medium band, despite generating tens of millions, most of that money is taken from you. You don’t even get to see it. You’re constantly kept in a state of debt which is a vulnerable position to be in. You’re always spending money on making videos, going out on tour, and particularly if you’re like me, you hate cutting corners so you want to work in great studios with great musicians. It meant I was in a very, very difficult position. A very vulnerable position because it’s almost like you have to keep on signing these bad deals to keep on going. So I thought, ‘You know what? I need to stop. I need to break out of the matrix.’ [laughs]

But you didn’t announce it?

MJ: I didn’t want to make any announcement. I don’t like those farewell tours. So I thought what better way to celebrate it than with Jim. He was at the very first The The concert at the front, before I knew him. He used to stand at the front of all of our gigs and he was such a distinctive looking character. And eventually I got to know who he was, we got to talking and we became very close friends. And I thought it would be nice to do the last show with him; it completed the circle. I’d been doing gigs since I was 11 years old with my first ever band, so that was almost a 30 year tour of duty. Hundreds of gigs in lots of different countries but I just didn’t feel passionate about it any more. So I put all of my equipment into storage, my lovely guitars and everything. I didn’t pick up a guitar for eight years. I’ve been living abroad in Scandinavia and Southern Europe for personal reasons. And obviously I’d had requests for interviews but I didn’t want to do them, I couldn’t see the point. But there was one request from a Dutch journalist Thierry Somers and he said, ‘What about we talk about politics and political songwriting?’ So we did that and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

But you’ve made some music since then haven’t you?

MJ: Shortly after that time I was asked to think about doing film soundtrack stuff from by a guy who used to work at a film music publishing house called De Wolfe which specialised in film and television soundtracks. And I’d always loved that kind of music. One thing I wanted to do while I was away was to make myself financially independent so that I could then not get myself into those dodgy deals any more. But my passion for music started to come back and that was initially through the soundtrack work. I also started getting interested in photography and I also started a little book publishing company. It’s a big world out there and the idea of just being on stage, singing the old songs again and again and again didn’t measure up.

Can you tell me about 51st State, your publishing company and its first publication, your dad, Eddie Johnson’s memoir, Tales From The Two Puddings?

MJ: My dad had always written. He was a docker and a publican but what he really wanted to be was a writer but in those days there were far less opportunities for working class families so he had to swallow his ambitious impulses and get on with working. But he always wrote [in his spare time] when we were kids and I can remember always hearing the tip tap of the typewriter coming out of his office. I used to enjoy reading his short stories when I was a kid. He was the licensee of The Two Puddings in Stratford between 1962 and 2000. I wanted to do something for his 80th birthday – he turned 80 in 2012 – and a few years prior to that I’d been talking to him about him writing his story and discussing sending it to publishers and then I thought, "Why don’t I just publish it myself?" I liked the idea of owning a small publishing company and there are ideas for other books in the pipeline but I thought that this would be the ideal way to start it and a nice present for him. He’s already working on a prequel – the war and national service.

What sparked the idea for Radio Cineola?

MJ: Well, I’ve always been a huge fan of shortwave radio. When I was living in New York, to counter the extreme propaganda that you get… I mean, the BBC is bad enough but Fox News is just unwatchable and unlistenable. Even the New York Times is full of propaganda. So to counter that propaganda I would tune in to The Voice Of Russia, Chinese radio, Cuban radio, in order to get a balance. I found something very exotic about shortwave radio as well. I like the way that it works because they are literally short waves, they bounce up and down off the ionosphere and that’s why you get that strange phasing sound. And it puts me in mind of the Cold War because it was a very hard thing to cut off. The internet now as powerful and wonderful thing as it is in some ways can be turned off like that if they want. But it would be very hard to block shortwave radio. So it was partially the interest in that. I don’t like the term podcast but I guess that’s what they are in essence; I prefer to call them miniature shortwave radio broadcasts because I feed it all through old equipment. I’ve got these old filter sets, which I’ve got for film soundtrack work and you can create all sorts of wonderful phasing effects. And I’ve got all sorts of analogue valve equipment to run it through to naturally distort the sound. And the idea is that it’s like a little jamboree bag, so you’d have an interview with someone that I was collaborating with a photographer or musician or film maker, some previously unreleased material and perhaps a preview of some soundtrack work coming up as well. So I liked the format as well. Actually you can rent these shortwave transmission towers and I was at some point thinking of doing some shortwave transmissions. I’ve got sixteen shows so I was thinking of renting one of these towers for the weekend and broadcasting them. I love analogue radio, I’m a big fan of it. I don’t own a television or a digital radio.

On Record Store Day you put out this wonderful 12”, which was a special remix of ‘Giant’ by DJ Food aka Strictly Kev. He’s kept the original feel and melodic nature of the track but he’s completely blasted it into new territory otherwise hasn’t he?

MJ: Yeah, he has. Kev is somebody who I really like. Not only as a person but musically and visually he is a very talented guy. He’s a very humble guy as well. We’ve become friends. Years ago he asked me to sing on a new version of ‘Giant’ and it remained a work in progress for many years. He would send me ideas and I would give him feedback. And eventually I did sing on it, I used my studio in London. I actually prefer my vocals on his version to my original version, they’re much better.

Do you have any more soundtracks planned?

MJ: Yeah, the next one, Hyena, will be released in September. That will also be followed up by a documentary that I’ve just scored called Penthouse North, which was shown last month at the Toronto Hot Docs festival. There is another soundtrack that I did, End Of Season which was premiered in Istanbul this year, so that’s three soundtracks which will be coming out over the next 18 months. And fitting in amongst that is a volume of poetry, The Inertia Variations – and some of this was broadcast as part of Radio Cineola. There’s a lot going on, in fact at the moment I’m having to turn soundtrack work down. So it’s just a case of time management really. I need two or three of me!

Matt Johnson will be interviewed by Strictly Kev on stage at Rough Trade East on June 30, the same day that the ReDISCovered box set of Soul Mining is released. The album is available for pre-order here