I meet Ned Beauman at a small but popular independent coffee shop in Central London just after lunch on a weekday. The street outside is busy and damp and small queues of people with poorly folded umbrellas form at the counter every few minutes. It’s nice enough but could be anywhere in the city or, really, anywhere in almost any major Western city. Like so many things, however, with the benefit of context things soon begin to take on a peculiar significance.

‘I’m actually not a coffee drinker,’ says Beauman, a cup of something which – given this new information – I am forced to concede that I can’t quite identify, pushed away to the right of our small table. (Beauman is incredibly polite and it is entirely possible that the cup belongs to the table’s previous occupants, having not wanted to bother the staff during their busiest period.) ‘Whenever someone says do you want to meet for coffee I say ‘yeah’. But I don’t even drink tea.’ (It isn’t tea.) ‘Sometimes I have a hot chocolate, but I’ve discovered recently that good hot chocolate actually has as much caffeine in it as coffee. I had a big hot chocolate at this really high-end hot chocolate place in New York and I felt like I was leaving my body.’

On the surface it’s a characteristically off-beat train of thought, totally erroneous to our discussion of his third novel, published that day, but on digging a little deeper the whole thing is actually a pretty perfect multi-level metaphor for the Best Young Novelist’s peculiar style and bibliographic trajectory. Much like our meeting today Beauman’s writing is in constant opposition with itself: it wouldn’t be right to say that nothing is quite what it seems in the worlds that he creates but, rather, that everything is something more than it appears and that the things that seem familiar – really, what is in that cup? – are, disconcertingly, just ever so slightly, off.

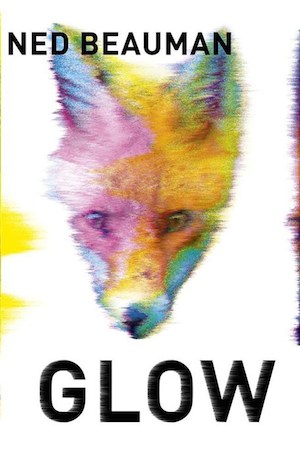

Glow is, to keep in line with the analogy, most definitely Beauman’s hot chocolate novel: an attempt to break with conventions that he has set himself – the confines of his now twice-visited themes of early twentieth century history, of parody and of palpable, acerbic cynicism. It’s a novel about London – the city where Beauman was born and for which he holds an almost unfettered fondness – and about the intricacies of youth. The difference is clear – it’s not coffee, it’s not tea – and, yet, the further you venture in to Glow the more that familiar, fuzzy sensation begins to creep in at the peripheries. By the end of the book there’s no denying that what you’ve consumed is, unmistakably, a hot, thick jug of Beauman.

It’s clear that the author is acutely aware of how his work to date is perceived; in response to the idea that Glow is something of a gear change in terms of its view of the world he smiles. ‘I can imagine people – particularly people that found the first two books a bit too cynical – saying, ‘well, why didn’t you do that from the beginning?’ but I don’t think writing about stuff that means a lot to you necessarily makes for a better book. I think sometimes that can be an obstacle: the enemy of quality.’ Coffee shops are good, convenient places to meet. Some books inherently require that they be written differently to others. Adapt to survive. It’s an elegant solution.

Spoiler: I never find out what’s in the cup.

Last time we spoke was when your previous book came out: you talked about how it was going to be weird doing your first book about London while living in New York. Having now read Glow – sure, it centres around London – it seems there’s actually more ‘other places’ in it than any of the previous books…

Ned Beauman: Yeah, that’s probably true. It was pretty clear from the start that Glow was going to be written from one guy’s point of view. One of the initial models for it was William Gibson’s recent trilogy: he’s really good at telling a story through three points of view – the people meet and then part and then meet it again and he does it so gracefully. I would have liked to do that, actually, but I don’t know if I could have pulled it off and it just wasn’t right for this plot, either. So, it was one point of view and that would have been the first time I’d written a book with just one point of view – I like my books to be very multifarious, I like them to have a lot of different things in them. I love writing about London, but the book just wouldn’t have had enough different colours and textures if it was only London.

While the last book was a sort of a vaguely side-eyed critique of a certain London scene at a certain time, Glow feels much less cynical and much more nostalgic – almost like a love letter to South London. Is that something that can only come from someone who’s writing from somewhere else, about somewhere that they used to call their home?

NB: I think that’s probably half true in the sense that if I had never moved out of Peckham then I’m sure my feelings about it would be mixed. If you live somewhere for a long time then statistically more unpleasant things happen to you there. I don’t mean things like getting mugged – breakups, that sort of thing – things just rack up and you start to feel more ambivalent about that place. But, I lived in Peckham for 2 years, right after I left home, and feel basically unadulterated warmth for it. I have thought about whether you can only write well about a place with a certain amount of distance and I actually don’t think it matters – I think I could have written about Peckham pretty much the same way if I was living there but I don’t know.

Was it important to you to convey more than an objective topography – to create something more like a feel or a sense – to evoke the spirit of the place? The best experience I had of reading the book was actually in Peckham, just outside the train station and that was probably the most complete sense of reading something I’ve had a in a while.

NB: Good. That’s good. Once I was reading the Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton in Washington Square – and it was the part where they walk through Washington Square.

In the book I’m actually pretty circumspect about exactly where they are because I didn’t want them to be confined by real street geography. But there are some locations that are real locations: like the tennis court they keep going to – that’s a real tennis court that exists precisely as I described it. When I was writing the book I was able to look at it on Google Maps. There’s that famous quote – it’s been quoted to the point of exhaustion now, though – about how you can compile a street map of Dublin just by reading Ulysses. But I didn’t want to do anything definitive about Peckham – I wanted to do something definitive about my experience of Pekcham and of South London.

The line I keep repeating is that I wanted to do for Peckham what Updike does for Reading, Pennsylvania in the Rabbit books. I really do feel like he swallows the city in those books. All of it. Every sunset and every weed and every shift change at the factory is in those books. I wasn’t going to do that but I wanted to at least grope in the direction of that kind of intensely observational style – at that mode of writing where your eyes are right up to the grain of it.

Speaking of Google Maps – you’ve travelled a lot over the last year or two – how much research, in terms of travel, in visiting of Glow’s various locations, went in to writing the book?

NB: Not much actually. In fact, I didn’t go to any of the places. I kept meaning to go to Burma and it just never happened. There are actually only really those two scenes and one of them is set in a shady mining village and the other’s set in an abandoned hotel. I guess I could have gone to places like that but I’m such a lazy and feckless and unimaginative traveler that even if I had gone to Burma I probably would just have ended up doing all the tourist stuff anyway and it wouldn’t have been useful. I didn’t go to Pakistan or to Guinea, either. I also did mean to go to Akureyri in Iceland for that one scene and I just never did. I just wasn’t sure if I could justify it for that one chapter and, actually, I wish that I had. I think you can tell – well, I don’t know if the reader can – for me, at least, there’s not enough detail.

If there wasn’t a lot of travel-based research, what about book research?

NB: Again, not so much I suppose. I read quite a few books about Burma – those were really helpful – and quite a few books about corporate dirty tricks and private security, and I read a bit about neuroscience.

But there were some real challenges: writing about Quetta, for example. No one goes there, so there are no tourist photos on the Internet. You kind of run up against the limits of your imagination – I had no idea what it would look like. I found some photos of other places in Pakistan and then, to my complete surprise and great joy, I found on YouTube, for some reason, that someone had filmed the drive from Quetta airport to Quetta town centre out of the window of their car – about seven minutes of video. It was perfect. Otherwise I don’t know how I would even have written that passage. It was the same with Guinea, really – there aren’t a lot of photos and, yeah, it’s tough. I don’t think it’s entirely laziness on my part – I don’t think even the most dedicated of novelists would go to Guinea just to write 1,500 words.

That being said, there’s clearly some research been done in to the various narcotic elements of Glow – n+1 published an essay of yours about buying drugs on the internet – maybe not first hand, but in some form?

NB: Oh yeah, I did a lot of Internet research. A lot of the drug stuff came off real message boards. I suppose it’s a very internety book in some ways.

Where did you get the idea for ‘Glow’ – the book’s namesake drug?

NB: I knew that I wanted the book to be a lot about light. The aesthetic of South London seen through the drizzle from the top deck of a night bus – which I think is becoming a bit of a cliché now – that aesthetic is so much about light; about streetlights or, say, when you go past one of those huge council estates and there’s a light above every door and it just looks like a spaceship or something. Also, the whole time I was drawing so much on Burial – think ‘Distant Lights’ – and I just love good writing about light. That doesn’t mean I’m good at it, but I wanted to give it a shot. So I knew I wanted it to be about light and I knew I wanted the drugs to be kind of like MDMA but also to do something else to you.

Otherwise I suppose Glow might as well be MDMA…

NB: Yeah, pretty much. The idea is that it has a different feel – that it’s different but it’s quite hard to articulate how it’s different. And, also, except in one flashback no one in the book is really taking it. So you really don’t know. As for how the plants react to artificial light and the way that they pass that effect on to the user – I just wanted Glow to be a real city drug. A drug about cities, if a drug can be ‘about’ something.

The process of creating Glow has roots in reality too – it’s referenced in the book, but it’s not unlike how Civet Coffee is made…

NB: I needed a way for foxes to be involved and then I thought of that Civet thing. I was actually a bit reluctant to use that because it’s such a punch line in many ways.

So, you knew foxes were going to play a part in the book even before you knew what that was going to be?

NB: Yeah, that’s right. It was a bit backwards, but foxes are so central to my – and I’m reluctant to use this expression, but – sensory gestalt of what walking through the city, through deserted streets, late at night is like. There’s nothing that really crystalises that feeling of having slightly slipped through into another world than seeing this extraordinary, beautiful creature. I’m a huge animal person – I’m really sentimental about and excited by animals, but the way that these things will appear and stare you down and disappear again as if they were never there sums up so economically the feeling I was trying to evoke in a broader way.

And, really, if I hadn’t at least mentioned a fox in the book I wouldn’t have been writing about South London – everyone sees them; it’s not just me.

Their peculiar otherworldliness is one thing, but having a byproduct of that Civet-esque Glow-creation process be heightened intelligence suggests you might’ve actually been looking for a way to humanise them a little

NB: Again, it was kind of a necessity. Eating Glow had to have some kind of effect on them – it wasn’t going to be that they had a euphoric rave experience because a) that would be inescapably comedic… too comedic and b) how would you be able to tell? It had to have some kind of perceivable effect on their behavior; I didn’t want them to become more aggressive, so all that I could really think of was that they would become benignly more intelligent.

I never thought of my self as a cat person, but my friend that I was living with in Brooklyn got a cat and I became a huge cat person. When you have a cat – and everyone thinks this about their cat – when you’re hanging out with your cat it’s just so hard to believe that it doesn’t understand everything that’s going on. You just cannot truly convince yourself that it’s incapable of speech and that it doesn’t have a point of view. You just assume that they get everything. It’s the same with foxes: when you have that encounter with a fox in the street it’s like ‘Come on, we both know what’s going on here. We could have a conversation if you wanted.’ That’s what it feels like. And that’s why it felt right for them to become more intelligent. Because it kind of feels all along like they are actually, secretly, just as intelligent as us.

Glow has a pretty expansive storyline – which isn’t uncommon in your novels – but the feel of it is completely different. It might be kind of a dirty word but, airs and graces aside, it’s a thriller isn’t it?

NB: Yeah, it’s totally a thriller. I wanted to write about corporate imperialism and private military companies and I wanted to write about pirate radio and those are both the kind of shadow worlds that, together, are just quite thrillery material. I wanted to write about South London in the present day and if I’d just written a literary novel about South London in the present day where people have emotions and go through life changes….

You’d be writing a Tao Lin novel about South London.

NB: That’d be pretty great, actually. But I’d just be writing a more conventional literary novel and that’s not really my thing. There’s a lot of people who do that and who do that very well. I’m just not interested in doing it my self. There had to be something else to it and the first place my mind always goes is adventure: as soon as you’ve got someone having an adventure in the present day, that’s a thriller isn’t it?

It’s not quite your shortest book, but – despite of its geographically sprawling narrative – it does feel more streamlined than Boxer, Beetle or The Teleportation Accident.

NB: Yeah, It is pretty pacey and it is more streamlined and I’m sure it’s quicker to read. I think one of the effects, weirdly, of writing in the present tense is that it makes people read quicker – it doesn’t make complete sense, but I think that’s true.

Raf is a totally different character to any of your previous protagonists – I don’t feel like I need to shower every time I empathise with his situation or his way of thinking like I did with, say, Egon Loeser. Was creating a less detestable, actually pretty likeable, character something that you set out to do this time?

NB: I didn’t start from that but this time I was writing about stuff that I feel genuine personal fondness for. The first two books had a kind of nihilism and flippancy and self-destructiveness to them and kind of ruled out from the beginning the possibility of taking seriously anyone’s emotions or attachments. But this time it wouldn’t have worked to take that tone – it would have gotten in the way of paying tribute to those things. So the tone of the book is more benign, which meant that the character is more benign.

It’s a much less cynical book overall

NB: Yeah, this is a really sentimental book. It’s really dewy eyed. It’s about Young Person Stuff.

On a personality level it might be true that Raf is ‘less interesting’ than someone like Loeser, but he isn’t totally devoid of his own shape. Where did you get the idea for his non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder?

NB: So, a friend of a friend – a friend’s boss or something… someone who I haven’t met – has a related syndrome where, basically, you’re just delayed. You have teenage circadian rhythms and just want to get up at 11 every day and go to bed at 2, which makes it really hard to hold down a job – everyone just thinks you’re lazy but it’s an issue in your brain. I was reading about that and stumbled on to non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome which is totally real and it just seemed right for the book. I wanted there to be the sense that three a.m. is just as much of a time as two p.m. – that three a.m. is just as important and midnight doesn’t mean anything and dawn doesn’t mean anything and dusk doesn’t mean anything. Every time is on the same level as every other time. There’s just a flat spooling of time.

The book was about London at night and about people living their lives on different timetables – so when I read about that it just seemed perfect for the character. And, also, it was useful in other ways: it isolates him and makes him see things differently. It makes him a better hero. The original plan was that the book would take place over one full cycle – over 25 days – so that over the course of the book you would have the whole cycle of Raf’s sleep moving in and out of phase and back to the beginning. But the stuff that happens in the book just doesn’t last 25 days.

Okay, so, that’s real – how much of the other biological or neuroscientific stuff in the book is actually real? Does drinking vodka right after orgasm actually stop the brain from wanting to pair bond?

NB: No, I came up with that my self – though I’ve no idea if it could work. But she admits that its folk neuroscience and I suppose there’s at least some substance to it in the sense that alcohol really does interfere with neurotransmitter release. So, in principal, if you’ve got a lot of alcohol in the blood going to your brain it’s probably not going to be ideal for oxytocin response but whether it would actually do enough to change your behavior…. No, there’s no substantive evidence for that as far as I know.

You thank two professors – who, perhaps naively, I assume are real – at the back of the book, so presumably something somewhere in there is close to legitimate science?

NB: It wasn’t so much about specific science as it was about a certain point of view. For example, when Win is posting on the message boards about how it’s ridiculous to assign a specific behavior to a specific neurotransmitter. The only reason we blame everything on dopamine and oxytocin is because those are fashionable neurotransmitters and they get loads of research funding. But there are dozens of other neurotransmitters that may be just as important: it just depends on the priorities of science at any given time. I find a lot of the scientific material about oxytocin pretty convincing and I feel like often those findings reflect things or even explain things that I find in my own life.

I didn’t put this in the book but something that was really fascinating was that when I asked ‘if crack releases dopamine and listening to classical music also releases dopamine then why do people get addicted to crack and not to classical music?’ the answer was that there is no real difference. It’s just socially acceptable to listen to a lot of classical music and not socially acceptable to smoke a lot of crack. We only say people get addicted to things if they’re things that they’re not meant to be doing. If it’s something we accept or something we admire then it’s just ‘oh, he’s really in to that’. Obviously that’s not entirely true – no one goes through physical withdrawal from classical music – but what this guy said was, basically, there aren’t different types of pleasure: neurochemically there’s only pleasure, different activities that produce it and different social roles for those activities.

Glow is out now, published by Sceptre