One day in 1949, a fifteen year-old kid named Bob Moog built a theremin in his mum and dad’s basement. In itself, this was perhaps not such an extraordinary thing. He was far from the only teenager messing about with induction coils in those days and by his own admission, the thing "didn’t work especially well". But what happened next would change music, across the spectrum from classical to pop, for good.

The hands-free electronic instrument had been popular in the States ever since its inventor’s stay in the country in the 1920s and 30s. With concerts at Carnegie Hall and the Grand Ballroom of New York’s Hotel Plaza, and a string of articles in the popular press, for a while the quavering vibrato and unearthly swoops that would later become a staple of Hollywood sci-fi seemed to be everywhere. By common consent, the very acme of ‘the music of the future’.

Even long after the return of Theremin himself to the Soviet Union (where he would find gainful employment bugging the U.S. Embassy – and even Joe Stalin himself – on behalf of NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria), his ‘etherphone’ device continued to pack houses in the mid-west. Composer Bernie Krause still recalls seeing one performed onstage when he was a small child in Detroit, during World War Two. And with the war over, the electronic hobbyist craze jumpstarted by Hugo Gernsback’s publishing empire was boosted by a flood of cheap war surplus valves, capacitors, and other bits and bobs.

On his way home from school, the young Moog would make a detour to the electrical supply shops on ‘Radio Row’ in Lower Manhattan. His dad, an amateur radio ham, taught him how to solder when he was still in short trousers, and by 1954 the pair had gone into business together selling do-it-yourself theremin coils and kits. An ad in Gernsback’s Radio & Television News magazine published that year promises "step-by-step wiring instructions" and "easy-to-read diagrams" all fully included in the pack. The address listed the R.A. Moog Co. at the Moog family home on Parsons Boulevard, Flushing, New York, just a short hop from the site of the two World’s Fairs in 1939 and 1964.

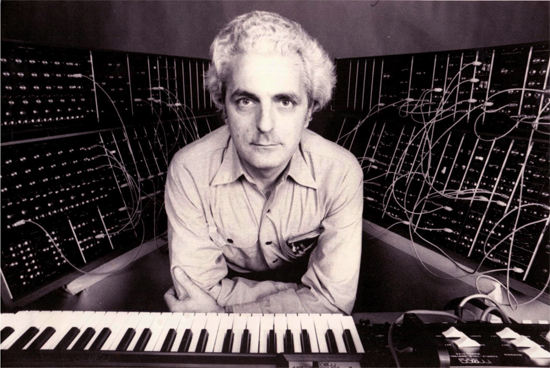

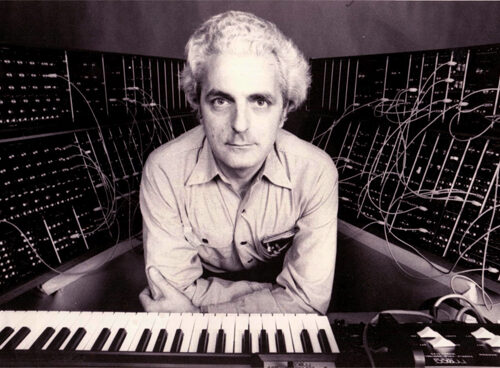

Nine years later, Moog was a physics graduate with a wife and kids, living in Trumansburg, a town with five bars and five churches and not much else, in Tompkins County, upstate New York. And he was still building theremins in his basement and selling them out of a shopfront in the village. All in all, it seems he was pretty happy building the electronic musical instruments and making out ok that way. Maybe he would have just carried on doing that, if he hadn’t met a guy called Herb Deutsch at the New York State School Music Association Allstate conference.

Deutsch had been teaching music out on Long Island, while Moog was there for the trade fair part of the conference, working the aisles trying to flog a few theremins. Herb already had one and was amazed to discover that its manufacturers, the R.A. Moog Co., consisted pretty much of one guy called Robert Arthur Moog and there he was standing right in front of him. The two got chatting and it soon became clear that Deutsch was way more switched on than the man whose machine would one day switch-on Bach. "Do you know anything about electronic music?" Deutsch asked Moog. Amazingly, for a guy who’d been building theremins half his life, he didn’t.

Deutsch invited Moog to a concert he was giving in the Greenwich Village loft of the artist Jason Seley, a sculptor who would end up as dean of Moog’s old alma mater, Cornell. This took place in January 1964. Downtown New York. Yoko Ono and La Monte Young had recently presented their concert series in her Chambers Street loft. Fluxus was happening. Jonas and Adolphos Mekas had set up the Film-Makers Co-op at the Bleecker Street Cinema. Archie Shepp and Cecil Taylor were doing gigs in people’s apartments. Yvonne Rainer and others had opened the Judson Dance Theater in a Greenwich Village church. Artists like Walter De Maria and Donald Judd were exhibiting works made of industrial materials like concrete, steel, plywood, and aluminium in co-operatively run galleries in the blocks between Houston and 10th Street. Moog stepped into the midst of all of this and it blew his mind.

In Seley’s loft, the engineer saw a work composed by Deutsch for electronically-manipulated percussion sounds recorded on tape, accompanied by a live percussionist striking one of the host’s seven-foot sculptures made of car bumpers. To Moog this was "absolutely the most exciting musical performance I had ever seen up until then". As soon as it was over Deutsch and Moog started talking about the possibility of building a "portable electronic music studio".

"What do you want to be able to do, Herb?" said Bob.

"Well," Herb replied, "I want to make these sounds that go wooo-wooo-ah-woo-woo."

Living and working on the opposite side of the country, making sounds that go wooo-wooo-ah-woo-woo was Paul Beaver’s stock-in-trade. A professional sound effects guy for Hollywood movies like Creature From The Black Lagoon, Beaver had a whole range of different electronic instruments, each one with a fairly limited compass of sounds and uses: a Novachord, an Ondes Martenot, oscillators and pitch generators, as well as several theremins. His former collaborator Bernie Krause recalls Beaver setting up his gear "on a ten-metre long table on a Hollywood sound stage" and working through a repertoire of noisy and numinous effects.

When Krause and Beaver heard that a guy over in upstate New York was putting "all those disparate technologies into one unit" they knew it was going to make their job a whole lot easier. But also, Krause told me via Skype, "the idea of the Moog synthesiser led us to think that we could also do some music with that as well, not only sound effects".

The Moog was not the first modular synthesiser that Krause had encountered. As a student at Mills College, he had used the Buchla Box, a device invented quite independently in Berkeley by the guy who built Ken Kesey’s sound system for the Merry Pranksters’ bus, Furthur. He still recalls his first lesson on the Buchla from the composer Pauline Oliveros, a teacher at Mills at the time. "She walked into the studio and I said, well, how do you get this thing to make noise? She said, just remember: outputs go to inputs. And she walked out. That was my synthesiser lesson. And it worked."

But on the whole Krause found working with the Buchla a "frustrating" experience. "The problem was that the instrument that was at Mills almost never worked. There was always a problem with it." The unreliability of the Mills machine could hardly have contrasted more decisively with Krause’s experience upon visiting Moog’s factory in Trumansburg. The inventor "set up the synthesiser on the edge of a table and said, here’s my bench test for stability, then shoved it off the table. It crashed onto the floor, several feet below."

Krause and Beaver were horrified. "This is a fifteen thousand dollar instrument!" But sure enough, Moog simply picked it up and plugged it back in and the synth worked as good as new. By the time the pair took the plane back to the California, their bank balances were each 7,500 dollars lighter – their life savings at the time. For a while it looked like they had made a dreadful mistake.

Over six agonising months, from the beginning of 1967 when the Moog was delivered, Beaver and Krause schlepped around the west coast, going from record label to record label with demo tapes and letters of introduction. They saw over a hundred different companies. "Nobody would pay any attention to us." With their last remaining few hundred bucks, they splashed out on a stall at that summer’s Monterey Pop Festival. It was probably the soundest investment of their entire lives.

Monterey Pop was a "convergence of a lot of talent in one place at one time." Krause describes A&R men walking around with contracts stuffed into their shirt pockets. "They would just pull these contract papers out from Columbia and CBS and Warner Brothers, and sign groups, fill in the blanks." Before they left the festival, Krause and Beaver had sold around fifteen synthesisers. "The problem was that most of the groups were too stoned to play it."

From having no hope and almost no money, the pair soon found themselves the hardest working couple of guys in Hollywood, putting in eighty hour weeks working as west coast sales reps to Moog, adding electronic effects to films like Bullit, Point Blank, and Performance, and teaching groups like The Doors, The Byrds, and The Monkees how to use their new toys.

The Moog was an incredibly versatile instrument. Even going into the 1990s, composer and session musician (and, of course, soon to be half of Goldfrapp) Will Gregory found that he could "do more" with even the slimmed down Minimoog than he could with the much later digital synth he had at the time. But whether in film studios or music studios, Krause and Beaver kept being asked to pull out the same tricks and replicate a certain sound they’d made on some hit record or other.

Despite the ocean of possibilities, a set of Moog clichés were crystallising. That, and being "tired of the drugs, tired of being inside the whole time," plus "bad musicians’ jokes", meant that as the 60s turned into the 70s, the pair were starting to get increasingly sick of their success. In 1975, Beaver died of a heart attack. In 1979, after being fired eight times while working on Apocalypse Now!, Krause quit the music business to study bioacoustics and take up field recording full time.

"I just wanted to be outside," he told me. Back at the end of the ’60s, he and Beaver had recorded In A Wild Sanctuary, the first commercial album to use natural soundscapes as an integrated part of the orchestration. Coming from a family "where a goldfish was nature", Krause found himself for the first time face-to-face with real wildlife, poking a microphone on a boom stand right into its habitat.

"That moment really changed my life," he says. Afterwards, "I just spent every spare moment I had out in the field, recording more sound. I began to hear the sounds of the natural world as cohesively structured, in ways kind of like the instruments of the orchestra are structured when writing a piece of music.

"Each of the instruments has its own niche where its voice can be heard, unless the composer is purposely blending them together. All of the critters in a healthy habitat do exactly the same thing. If their behaviour and their survival is predicated on their voices, then the transmission of their voices and the reception of their voices needs to have clear channel in order to be transmitted and received."

He credits his experience with electronic sound – "drill[ing] down into the main components of a sound" – as foundational to this new appreciation of the natural soundscape. And its this understanding that has led to The Great Animal Orchestra, the piece he will be presenting at this year’s Cheltenham Festival.

Will Gregory’s earliest memories of electronic music date from around the time Krause was quitting the business altogether. "I remember Devo having these kind of waah animal rasps, Giorgio Moroder’s [production on] ‘I Feel Love’, Kraftwerk… I remember a cartoon picture of people playing ping pong off the walls and below there is somebody looking at the ceiling saying, I wish they would stop playing their Stockhausen records."

A few days before Krause’s Great Animal Orchestra, Gregory will be at the Cheltenham Festival with his Moog Ensemble, a chamber dectet of analogue synthesisers featuring composers Graham Fitkin, Viv Hope-Scott, and Eddie Parker along with Portishead’s Adrian Utley and others, performing works by Bach, Messiaen, John Carpenter, and Gregory himself.

It was Utley who first whet Gregory’s appetite for the analogue sound. "He had a Korg MS20," Gregory told me, "and he said, come over and try it. That set me off on a bit of a collecting journey." Since then, he’s built up a formidable arsenal which he justifies to himself "and significant others" with the promise that each new synth will have at least one unique sound that may "open a new door to some rich seam of sound that you can mine" to inspire a composition.

"There was this amazing period when synthesisers were coming out thick and fast," he says. "It felt like a sort of arms race between nations producing synthesisers. A lot of them have things on there that you just don’t know why they put them on there. Other times they have things on which are just totally brilliant and totally game-changing. With a distance of time, some of them stood the test and some have proved to be these evolutionary dead ends."

Amongst all these different evolutionary paths and possibilities, Gregory cites the Minimoog as particularly prophetic. "Even now, synthesisers tend to look exactly the same. They got it so completely right out of the starting gate."

He still remembers the first time he got to play one. "It just roared," he exclaims. "This incredible idea that this thing made of chips and circuits and all these very mathematical and scientific components could make a sound like it was coming out of London Zoo."

The key to the Moog’s longevity, for Gregory, lies in its inventor’s attentiveness to the needs of musicians. Herb Deutsch practically moved in with Moog’s family for weeks when they were developing the first prototype together, and later Eric Siday and Wendy Carlos would each have a profound affect on the machine’s further development and refinement.

"He wasn’t isolating himself like a presumptuous laboratory scientist saying, I know what’s best," Gregory told me. "He was going to musicians and saying, what would you like to be able to do?" Krause agrees, telling me that compared to the Buchla, "I found that the Moog synthesiser was a little bit more intuitive and also, in terms of a transitional instrument, more musical. Moog was more interested in helping people make the transition between the vagaries of electronics to really controlled expression of music."

It’s this concern, finally, as much as any engineering chops, that has secured Moog’s place as – in Gregory’s words – "the Stradivarius of the synthesiser".