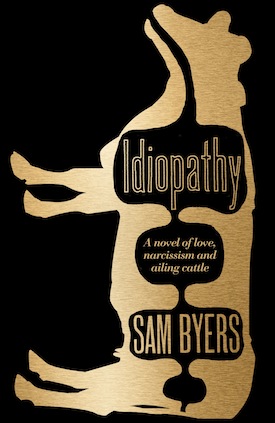

Sam Byers’ debut novel, Idiopathy, is a glibly-humorous portrait of thirtysomething discontent – a wry examination of boredom and narcissism in contemporary society. Erstwhile lovers Katherine and Daniel are Idiopathy‘s co-protagonists. They share a past and a city: Norwich. Katherine – jaded, cuttingly sarcastic, and as internally angst-ridden as she is externally confident – has taken up with a louche, self-absorbed lothario named Keith; Daniel has settled into a life of twee domesticity with affectionate, animal rights-loving homemaker Angelica. When the unexpected reappearance of a long-lost mutual friend forces Katherine and Daniel to re-enter one another’s lives, their myriad insecurities, neuroses and unresolved issues are thrown into sharp relief.

Part comic farce, part social satire – and with strains, although one hesitates to say it, of straightup romantic fiction, Idiopathy was published last year to a warm critical reception. It was shortlisted for the 2013 Costa Book Awards, and listed as one of the Daily Telegraph’s Books of the Year. Its author lives in Norwich, where he is currently completing a doctoral thesis on David Foster Wallace at the University of East Anglia. I spoke with Sam about some of the big existential questions addressed in his novel: about self-doubt, self-help, self-improvement, and other things that begin with ‘self-’.

Reading Idiopathy I was frequently reminded of Flaubert and his preoccupation with boredom – with what he called ‘that modern boredom which gnaws the very entrails of a man.’ It seemed to me that the ennui endured by your characters – the navel-gazing, the narcissism, the insecurity and uncertainty about how one ought to live – is essentially the 21st-century incarnation of that same sort of boredom. Your doctoral thesis is on David Foster Wallace, who was similarly obsessed with itemising those private hells of self-doubt and self-loathing. Will you be returning to these themes in your next novel, or will you be going in a different direction?

Sam Byers: I think you’re right to draw a link between boredom and narcissism. Narcissism is, after all, essentially a disease of privilege in that worrying about yourself all the time is a sure fire sign that you don’t actually have enough to worry about. But I think what has changed since Flaubert is this greatly inflated awareness of some ideal self we are supposed to live up to. We’re bombarded by advice: not just on, as you put it, how to live, but also on how to actually be. On one level this great ongoing conversation about our collective and individual emotional wellbeing is extremely important, but another level it has actually just been corporately hijacked and shaped into another tool to make us all feel inadequate so that we spend money curing an inadequacy that doesn’t exist. Wallace, of course, understood perhaps better than anyone how a certain kind of pseudo-emotional discourse could be extremely liberating on the one hand while being profoundly disempowering on the other, and he was able to deconstruct and interrogate that discourse through partially appropriating it in a way that at this point feels pretty definitive.

As far as the next book goes, it’s very difficult to say. I’m still fascinated by the extent to which we are the greatest cause of our own unhappiness, which I guess you could think of as self loathing to some degree. But I hope there will be room for some happiness too. I think cynicism is very easy – a reflex, almost. I want to find a way of writing about emotional experiences in a way that’s nuanced enough to leave room for things like joy and love whilst still picking away at what I see as the scabs on our culture. It’s very difficult though. I wouldn’t expect too many changes over the course of one novel, but ask me again in twenty years and we’ll see how I’m doing.

Katherine’s on-off fuckbuddy, Keith, is diagnosed with sex addiction; he gets short shrift from the narrator. I was reminded of the Steve McQueen movie, Shame (2011). It’s about one man’s struggle with his compulsion to engage in joyless rutting and/or beating off, 24/7. The film’s reception was interesting because it indulged this insidious contemporary fad for pathologising human behaviour, human flaws. It’s like this old-fashioned moralism masquerading as modern science. Idiopathy is laced with withering contempt for pop psychology. As well as the bit about Keith, there’s an acerbic send-up of the self-help industry and its specious do-gooding. Has it all just got a bit out of hand?

SB: Well, I think that’s exactly where we’ve got to, collectively: the point of asking that question. There isn’t a simple answer. On one level, I think this idea of a public conversation about our emotional lives is incredibly freeing. I think more than any other previous generation we have been brought up with the idea that we need to pay attention to what we are feeling, and try and understand it, and I think that’s all to the good. I also think, at a very basic level, the idea that a person who is grieving, or lonely, or going through divorce, can just walk into any bookshop and find something there that will offer them comfort and perhaps even some reasonable advice about how to manage that situation, is a very good thing. So I’m not cynical about the idea of that ongoing conversation. What I am very cynical about, and what I think Idiopathy is very cynical about, is the idea that people who are suffering have become little more than an easy source of revenue for greedy, opportunistic sharks. Somewhere along the line, feelings have become commodified in a way I find profoundly distasteful and, at worst, abusive.

Physical wellbeing emerges as a theme in your work. You wrote a blog piece for the New York Times on your attempts to quit smoking; Daniel, the co-protagonist in Idiopathy, is self-consciously abstemious to the point of blandness. You’ve spoken, in other interviews, about having taken up running – I’m in my early 30s: all around me people who spent their 20s partying hard are taking up yoga, pilates, zumba, etc. with an enthusiasm redolent of religious conversion; the runners are the most zealous of the lot. (I’m not excluding myself from this – I go to the gym like five times a week.) Is this, perhaps, a manifestation of the very malaise you satirise in Idiopathy? Like, you get to a point your life and suddenly there’s this big moral panic to start doing things right and, like, save your soul?

SB: It’s an interesting question. I think it’s difficult to draw any wide-ranging conclusions about it because it’s different for everyone, but my personal experience is just that it takes a couple of decades to stop taking yourself for granted, and to value yourself and start taking care of yourself properly, and once you do it’s pretty difficult to stop. It’s interesting you use the word blandness. I remember when I gave up smoking I thought: ‘that’s it, I’m going to become boring very quickly from here on in.’ But actually there’s nothing more boring than listening to a smoker justify their smoking for the billionth time. Indeed, arguably the only thing more boring is listening to someone who’s completely wrecked talk about how wrecked they are.

If you want to get philosophical about it I think it’s actually about the way our relationship to meaning changes as we age. When you’re a teenager, or perhaps in your twenties, you think meaning is something ‘out there,’ that you have to go and ‘find.’ You tend not to have an intimate relationship with your own body or mind because you’re still, basically, exploring. It’s a good time to take drugs because you’re both searching for something and also running away from something (reality). But by the time you reach your early thirties your body is a bit less able to cope with the damage. You’ve probably frightened yourself a couple of times. And at the same time you’’e beginning to realise, and I don’t mean this in a depressing way, that there’s nothing out there. The most immediate reality and meaning you have is your physical and emotional presence in the world on a minute by minute basis. In light of that, being mentally in the stratosphere and physically in the gutter starts to seem a little precarious. As Simone Weil said, the body is a lever.

If you want to be less philosophical about it, I think the other key factor is that you start to feel old, and you realise you’re not quite ready to die, and that coughing your lungs up and battling a hideous come-down and basically realising you’re a wreck starts to feel a whole lot less romanticised and a lot more terrifying and it dawns on you that you’d better shape up.

It’s true that the whole ‘I’m really virtuous’ routine can be incredibly self-satisfied and pious, but, god, I don’t miss talking about the universe with potheads at all. Nor do I miss being that pothead. When I wake up in the morning now I’m able to think, very clearly and very happily. It’s a feeling I’m increasingly reluctant to part with.

Idiopathy is out now, published by Fourth Estate