Anniversaries are a funny thing, they come around whether you like it or not and – like the good press against the bad – you’re stuck remembering the passings and break-ups as much as you are the big birthdays. So it is for Hole’s seminal second album Live Through This, released 20 years ago this month. From the very moment it blinked into the world the record has been hung heavy with spectres. Black Flag roadie Joe Cole, shot after attending a Hole gig in 1991; bassist Kristen Pfaff who died of a drug overdose two months after the record’s release and Kurt Cobain’s suicide, which stalled the album’s bolt from the gates entirely. At an awards show in 1995, Courtney Love begins a performance of the album’s opening track ‘Violet’, by exhaustedly dedicating it to a list of lost souls: "Kurt, Kristen, River, Joe… this is for you."

She and mainstay guitarist Eric Erlandson had seemingly penned Hole’s ‘survivor’ record before the tragedies had even taken place. The timing was terrible. The timing was perfect. "I’m not psychic," said Courtney Love, in an emotional interview with MTV, just months after Cobain’s death, "but my lyrics are."

But maybe that’s utterly wrongheaded – or at least only gives you one very slight, very convenient reading of the album and its persistent guttural roar. Listening back to it now, as news of new Hole material and live dates are shadowed by Nirvana’s inauguration into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame (such is the anniversary’s cruel catch), Live Through This sounds to be about a very different kind of survival; that of growing up a girl.

The twelve tracks create an exceedingly female space, with a dark flurry of issues concerning identity, sexuality, commodity, success, friendship and feminism circulating Love as the band’s centrifugal force. In her recent Woman’s Hour interview, Love admitted her inability to write co-dependent love songs – co-dependent hate songs being a different matter – and in evading that convention, Hole succeeded in establishing a very different tone of voice.

The record’s autobiographical allusions are as mercurial as its status as tragic prophecy (is ‘Violet’ really about Love hexing her ex Billy Corgan and making him bald?) but the one thing you can rely on is a pervading sense of female defiance – a raw capture of the bitter-sour achievement of winning Miss Congeniality while your insides and sense of self crumble into ash. "Yeah they really want you, they really want you, they really do…" goes the memorable lyrical tease of ‘Doll Parts’ – a doomed breadcrumb trail of encouragement and desire.

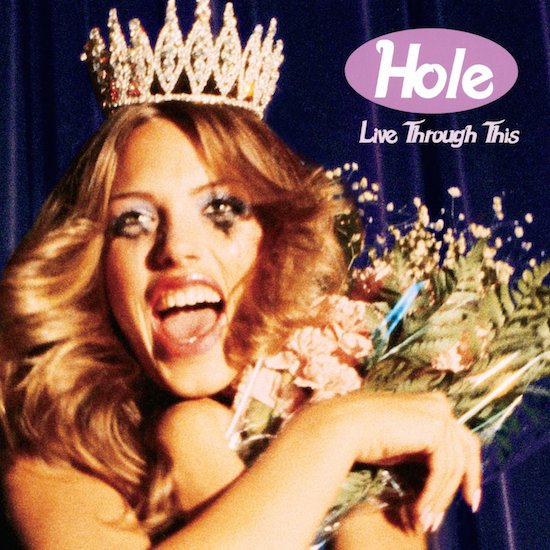

This tug of identity wars is epitomised by Ellen Von Unworth’s cover art which features a dishevelled but ecstatic beauty queen on one side and a pre-teen, pre-nose job, pre-attitude snapshot of Love on the other – the images bookending a slew of songs that chronicle everything she’s apparently dragged her way through from one to the other.

Love saw herself as an ugly duckling in the early days of Hole, and has gone on record alleging that no one of note would fuck or sign her until she fixed her nose and lost her puppy fat. As a yobbishly vocal feminist this seems jarring. Why did she care enough to become that person? The answer seems to lie in a weaponising of beauty, of pushing the limits of textbook femininity over the edge with a candy painted nail and a siren song. Hole’s music – and in particular Love’s lyrics – didn’t work to crack the mould of empirical prettiness, but rather embody the dark dichotomy of enforced perfection. Where other Riot Grrls staunchly (and legitimately) refused to cosy up to such ideas, Love embraced her beauty privilege in order to subvert it. ‘Doll Parts’ and ‘Miss World’ are the aural incarnations of this subversion, the former being an anthem to utter detachment and emotional dismemberment and the latter putting it even more bluntly – if that were possible: "I’m Miss World/ Somebody kill me."

The same could be said of the album itself which is endlessly more melodic and nuanced than their debut Pretty On The Inside. There’s beauty and brightness in the picked acoustic and slide that drives ‘Miss World’ to its defiant conclusion; the adoptive glassy delay and echo of their bolstering cover of Young Marble Giants’ ‘Credit In The Straight World’; the rangy space of ‘Softer, Softest’; the melancholic lilt of the "rose white/ rose red" chorus from ‘I Think That I Would Die’; the sinister lullaby of ‘Jennifer’s Body’.

But despite all these sonic pleasantries, the record’s underlying growl is irrepressible, and Love’s husky roar the perfect counterpart to the rock solid band she assembled in Erlandson, Pfaff and drummer Patty Schemel. Her angst is instantaneous and eloquent and the shifting scale of her voice – from smoke laden, to girlish, to a squeal that almost evades the upper limit of human hearing – is a distillation of everything a tormented female feels but cannot express.

It’s a collective howl. As 17-year-old blogger and voice of her/a generation Tavi Gevinson writes of the album: "Hearing them can be like when you’ve been sitting in silence and then are startled at the sound of your own voice, but in this case its someone else’s voice, and they’ve articulated what you wanted to voice perfectly, at times without having to be very articulate at all. To confront this voice is to feel free, for at least 38 minutes and 23 seconds."

The breathy vocal run up Love takes to the incendiary bellow of "FUCK YOU" three quarters of the way through ‘I Think That I Would Die’, is a fuck you on everyone’s behalf. It’s the kind of fuck you that you keep as a talisman – in your headphones or scribbled hard in biro – and it’s always there to come back to.

This again, is where Live Through This diverges from other Riot Grrl music of the time, in its unabashed universality and broad populism. Rather than allying with any specific political niche, Hole made a record that more or less anyone with an alternative rock sensibility could get into. While we owe more than we can name to Riot Grrl’s originators, to the violent independence of bands such as Bikini Kill and the radical feminist community they spearheaded, there is always a sense for young women approaching the edges of feminist thought for the first time, that if you weren’t there, you can’t identify.

I’ve felt this in Gender Studies classes as a student – admiring the relentless political energy of the first-wave from an un-crossable distance. I feel a little like that toward the Riot Grrls of the third-wave too. Not matter how akin to its values I feel, I was too young. I missed out. I was raised on pop music. So where does that leave me?

The way that Live Through This directly responds to that particular dilemma is thanks – in part – to a cruel twist of fate. Following Cobain’s death, the band made the decision to switch in a scrappy outtake version of ‘Olympia’ in place of the intended closer ‘Rock Star’, which contained a direct lyrical reference to Nirvana that would have seemed crass in light of his sudden demise. The sleeve notes were already printed so the song retains the previous title; a crashing sonic jibe at what Love saw to be a humourless and samey brand of Pacific North-western feminist rock, becoming an accidental pennant for her brand of creativity. "What do you do with a revolution?" she demands of her peers. "Do it for the kids," comes the insistent, repetitive coda.

This kind of feminist civil war may sound counter-productive and like just another incidence of Love’s wilful, almost recreational antagonism. But what if you look at it another way? As a bold move that – in attitude – devours that historic distance and extols the virtue of a different kind of feminism; one that doesn’t have to conform to a particular type of consciousness or activism in order to be legitimate.

Whether or not it was to this attitude that the record owes worldwide sales of over two million, (nothing to sniff at) it’s certainly what has made it enduring; a go-to album for young women like Gevinson and many others, some twenty years after its release.

On either side of Love’s particular devastation in the April of 1994, there was stuff to endure, a cacophony of personal experiences (self-inflicted and otherwise) that were lived through. Fatally imbued as it is with the connotations of a relationship that will forever define Hole’s history, and rich as it is in imagery of Love as a latter day Scarlett O’Hara, single minded, fame grubbing, self-involved and prideful, Live Through This provides endless, powerful sloganeering for women and girls everywhere in need of a vocal outlet. Love knew that the way to infiltrate as many ears as possible was to make pop music – and this record is Hole’s diamanté-adorned, cracked plastic crown-ing glory.

It’s arguably a record for everyone – but it smells, unmistakably, like girl.