"…some sort of euphoric, wild joy and indulgence in beautiful, chaotic noise" is how James Johnston, leader of Gallon Drunk, neatly described their new album, The Soul Of The Hour, while chatting in a Lambeth boozer on the eve of its release. But the phrase sums up perfectly the essence of the band’s output over the past twenty-five years. Never shy of acknowledging their influences, each Gallon Drunk recording or performance distils a connoisseur’s history of rock – from the electric blues blueprint of Howlin’ Wolf and Link Wray, through the embryonic punk of The Stooges and Suicide, to the post-punk mutations of Public Image Limited and The Birthday Party. While they deftly channel this long lineage in their every riff, rhythm and roar to guarantee that feeling of primal promiscuity and justified jubilance that only the best rock & roll inspires, it doesn’t explain why every one of their songs consistently carries the same indelible stain. Right from their earliest recordings as a two-piece the mark is there: a uniquely cool yet ostentatious finish.

And The Soul Of The Hour is, thankfully, no different; while its differences to previous Gallon Drunk records are intriguingly abundant. It starts with ‘Before The Fire’ their longest track to date – a rousing ten minute, cinematic odyssey, whose first half lulls its listener into a false sense of security: through the measured interplay between their Cuban/voodoo drum sound and a delicate jazz piano the piece slowly builds into a slowly surging noir anthem. New single, ‘The Dumb Room’, kicks in next, recalling the funk and fire of ‘Foxy Lady’ by Hendrix spliced with a punk rage, while the album’s title track is perhaps Gallon Drunk’s moodiest and most beautiful ballad yet – it’s sudden, unexpected transition from steady lamentation to bursting guitar noise entwined with brass fanfare forms a depth-charged shock, arguably as joyfully euphoric as rock can get.

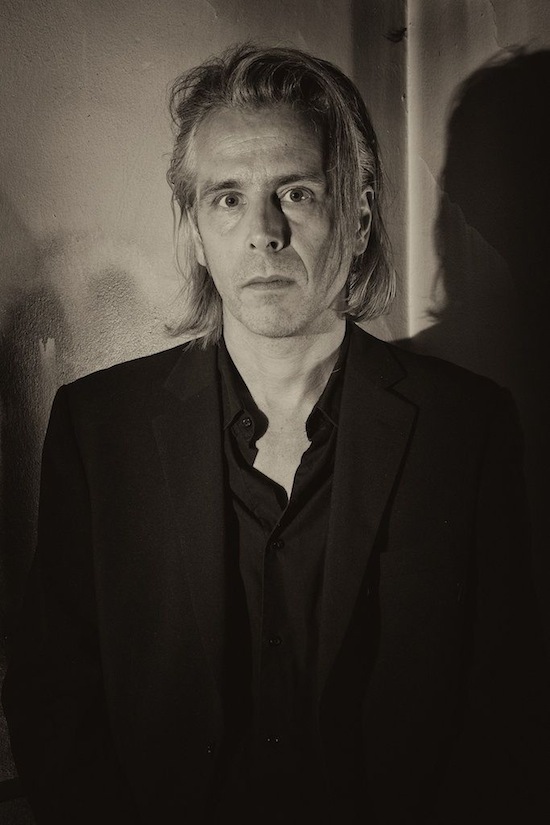

Freshly enthused straight from a band rehearsal for their upcoming tour, James Johnston discusses the long road that lead to their currently ascendant phase, revealing along the way how krautrock, an album by jazz arranger Gil Evans and even the gangster rap of NWA slid into their mental mix while preparing the new record…

James Johnston: On this one, we really consciously thought okay, let’s have no harmonica, let’s have no slide guitar, hardly any sort of open tune guitar, no solo saxophone – just have brass instead – or if there’s any sax we’ll put it through a wah-wah and amp and no one will know what it is. And Ian [White] really wanted to do a lot more motorik drumming style, but it still sounds like us even having done all that [laughs] which is great! It’s either our natural limitations or our natural style.

We’re trying to get comfortable with playing the new songs, because it’s quite a studio record in a way. All the arrangements, everything’s changing already with doing it as live stuff.

Is that the typical order that you work in? You don’t write on tour and then record?

JJ: No, it never really seems to happen that way. Obviously in year dot it did because we didn’t have any records, but predominantly I come up with the very basic idea to start with, either by humming a tune into a Dictaphone, or nowadays doing a quick GarageBand thing that I can then send to the others. With this one I must have done about 70 demos and they’re not finished – it is like an improv idea, and then I leave it and keep that odd song structure so that it still feels really fresh; and then we work on it from there and try not to knock it into a more conservative song structure, just leave that weird feel to it.

The reason there were 70 is that you could go through them [saying] "that sounds familiar, that sounds familiar – cross it out, cross it out" and get this little shortlist of 15 songs or so and try those in rehearsal and then whittle that down. So we were fairly prepared, but the vocals always come after the music, ’cause then the atmosphere changes. There’s a quiet song on the record – ‘Dust In The Light’ – when we were rehearsing it sounded more like the song ‘Johanna’ off [Iggy Pop & James Williamson’s] Kill City. Well, it sounded very much like that actually, and it nearly got left off from the list. Then, when we got in the studio I was trying to show Terry [Edwards, keys and brass] and Leo [Kurunis, new bassist] the chords, ’cause Ian [White, drums] was still in bed, so I was playing it really, really quietly, and the producer, Johann [Scheerer], stuck his head in the recording room going "What’s that, that sounds great!" and we were going "Oh, we’re just quietly running through it, we’ll do it properly for you later" and he was going "No, that’s brilliant, do it like that, just wait for Ian to get up and then we’ll tape it." We did it straight away like that and there was this totally different atmosphere. So, I’m glad I hadn’t written anything for it as it wouldn’t have fitted; I had to write to the sound of the music.

That’s interesting – has that been a consistent approach all along that you create music without thinking about the words?

JJ: …or the subject matter or anything. Yeah, absolutely.

So it’s all a focus on the sound?

JJ: Yeah, very much. Lyrically, it always starts with reams and reams and reams of pretty much automatic writing that I’ll have done on tour or wandering about; scraps of paper [to] go through listening to the song. You think, "Oh, God, that sounds like that" and then [you] pick another bit and another bit. It is a sort of juxtaposition – somehow these things suddenly present some sort of internal logic and then it almost presents its subject matter afterwards. I really like doing it that way.

The way you describe it sounds like a ‘cut-up’ method.

JJ: Kind of, yeah, initially, and then once something’s there it’s almost as if someone else has written it. Whereas, from the very blank piece of paper, I’ve always thought, "Oh God this is shit, I can’t do it, this is so shit" and never get anywhere. So, using that other way of doing things is like stealing a line out of a book of poetry, whereas it’s just something you jotted down two weeks ago.

There seemed to be a conscious change with the studio you used for this and the last album [2012’s The Road Gets Darker from Here]. Looking back, you seem to stick with engineers and studios – what was the attraction of the Hamburg studio [Clouds Hill] with Johann Scheerer [producing]?

JJ: Well, one, it’s a beautiful studio; two, it’s in Hamburg. You can totally focus – there’s really big live rooms, like we might have been able to get years and years ago when there were more large studios around, but it’s such a luxury to have such a large room so we can all set up together even though we didn’t necessarily play it all together on this one. And there are flats downstairs, so after recording you sit down and you listen to music together and it really, really helps for the whole process. Hamburg’s a fantastic city but for the initial recording we were there for about two weeks, and I think I left the building once! We feel so comfortable there and Johann’s a really great guy and very, very enthusiastic and positive. For example, for this one, if we were thinking, "Let’s try something different or any idea, however stupid – just give it a go" he really encourages that. It makes it easier if you know the people – if it doesn’t work no one’s going to look stupid, just fucking erase it you know? And time wasn’t such an issue so we had [that] freedom and I think it’s all the better for it.

You know we’re doing these long tracks, we do one take and then [say], "Oh, lets try another one", and we know that there’s only eight minutes of tape left, so you’re playing and there’s someone looking through the window miming at you – "You’ve got one minute [left]" – and all of that is exciting and really reinforces that you’re capturing a moment in time, really freezing the air – "Here we go, we’re going to get this" – and all the atmosphere and character that goes with it. It makes it feel more precious and that’s reinforced by doing it on tape.

Do you think the Hamburg location is part of the reason why you’ve ended up stretching the durations of the tracks?

JJ: Yeah, definitely. And they got a really nice grand piano to play and it sounds lovely and that song [‘Before The Fire’] wouldn’t have been anything without having that lovely big sound. The whole thing was [also] to get a really, really good drum sound and they’ve got some really nice vintage kits there, and so much time and care and attention was put into getting Ian sounding as good as he wanted, sort of using the John Bonham technique. And even though the record sounds live, that track started with Ian and I playing together, just the two of us, drums and the piano playing for whatever it is, nine minutes, and then he went in and played the second layer of drums, the one that really takes off, and then Leo did the bass. ‘Cause it sounds like a whole improvised group piece of music but it wasn’t actually done like that, we had a real plan for it that Ian and I had come up with. Originally it sounded something like ‘Little Doll’ – they all originally sound like various Stooges tracks [laughs] – and then Ian’s saying, "Why don’t we go a bit more down a sort of Gil Evans route, the jazz arranger?" and then it turned it on its head.

With the last album you mentioned that you listened to Exile On Main Street a lot while making it – what sort of records were you listening to while recording the new album?

JJ: Well, Gil Evans – a brilliant album by him called The Individualism Of Gil Evans, it’s fan-fucking-tastic! And Can; and NWA oddly enough, that came up quite a bit, it’s two particular songs that we were listening to: ‘100 Miles And Running’ and ‘Straight Outta Compton’, and those definitely influenced the last track on the record, ‘Speed Of Fear’, because we were trying to do something that sounded like krautrock but also like a James Brown 1970/71 drum beat but that odd, cut-up nature that you get with something like NWA, but [we] try and play it. But yeah we were listening to that a lot at night and probably Exile On Main Street again [laughs], Dr John, I don’t know if that really made any impact on it, Jimi Hendrix, I think that’s fairly notable on the second track. Oh, we were listening to Velvet Underground bootlegs as well, 20 minute versions of ‘Run Run Run’, that sort of thing; and Big Star, we were listening to them quite a lot.

I wouldn’t have guessed NWA I must admit.

JJ: Fucking brilliant, my God, so fantastic.

In terms of the tone of it, would you say the new album has a greater sense of anger than before?

JJ: I don’t know whether anger’s the right word, it’s sort of a combination of frustration and total release. I think we’re always trying to get that and some sort of euphoric, wild joy and indulgence in beautiful, chaotic noise. And a fucking brilliant drummer, that’s sort of it really. To be honest, certainly lyrically, it’s not particularly angry this one, it’s almost more out there and more romantic, and at the same time quite melancholy. When we were listening back to it, it had to be thrilling rather than overtly angry, which a lot of the other records veered towards. Some of the more obvious things we tried not to do, like these weird noises at the end of ‘Exit Sign’ – the temptation was to put a load of guitars leaning against amps etcetera. But instead I was thinking, "What can we do?" I was trying to hum this noise to Johann which he ran through this echo box and got this fantastic, total atonal weird feedback sound. It was ten times better than what I would have done with a guitar. It’s lovely, such a cool sound. For anyone nerdy enough, it’s this little box called a Fradan, which stands for something like ‘Frank and Dan’. It was made in the back of an electrical repairs shop in the Midlands in the sixties and it’s just this little tape loop, echo thing that you run anything into it and put it through an amp. We ended putting all of the vocals for the whole record through it, so there’s this odd ghostly sound, we put the bass through it, the organ through it, we put pretty much everything through it. It’s all those little things that you wouldn’t necessarily notice that give it a sort of uniform feel. Yeah, that’s a really cool little bit of kit, if anyone sees it on eBay I’d recommend getting it.

The album features your new bassist Leo Kurunis, how did you meet?

JJ: It sounds retarded but, in the pub – pretty much where we’ve met everybody. But he was a friend of a friend – Ian and I were doing a thing with Lydia Lunch, a one-off festival where we were going to be playing [Lunch’s solo debut] Queen Of Siam from beginning to end. It’s a shame we literally only did it the one time.

Where was that?

JJ: In Austria. But it was so good, it sounded so brilliant and we didn’t really know Leo. Someone said he played the bass and Ian suggested [him] and he was fantastic – we got on so well and then we were friends through that and it happened pretty naturally. We had been carrying on as a three piece before recording the last record because Simon [Wring, Gallon Drunk’s previous bassist who tragically passed away prematurely in April 2011] was ill and we always left it that he could come back anytime. So then we ended up recording the [previous] album as a three piece and then we tried to play it as a three piece and we just couldn’t do it.

Terry and Ian have been around for a long time.

JJ: Absolutely, not original members, but Terry joined probably early ’93 and Ian joined in November 1993. I remember we were auditioning two or three people, and Terry knew Ian through some sort of jazz group, and Ian had come straight from work at Phillips, the auctioneers. He came in a tweed suit and I thought, "He looks pretty cool", and immediately [when he played] I thought, "Wow, just brilliant." We had one rehearsal and then we played in Japan and that was his first gig; we had one rehearsal and he’s been in the band ever since. Terry joined earlier, came into From The Heart of Town [their second album released in 1993] to play the horns, so yeah we’ve been playing together for a very long time you know. Over twenty years.

How did you find Terry or did Terry find you?

JJ: He went to the same university as Max [Décharné], the second drummer in the band (who was around for the first two albums). We were playing with Madness, Ian Dury & the Blockheads, Flowered Up, Morrissey [at Madstock, Finsbury Park in August 1992]. I think they were trying to get people who represented British music, so they asked Morrissey and he said he’d do it if we did it, ’cause he’d seen us play at the Scala Cinema. So we ended up playing [Madstock], and [Terry] had a saxophone with him and came on and jammed with us; we did a long version of some song – I said to Terry, "Just think of Funhouse and the song’s in E and see what happens," and, you know, straight away it was brilliant. And then Ian joined and the whole band was suddenly like "Wow!" It was ten times better, and the three of us have played together ever since. It’s very instinctive now. We’re really, really close friends, and we’ve been through so much together, so now it’s so lovely having this real enthusiasm coming in with Leo. He’s a fantastic bass player as well and really, really fun, lovely person. When you’ve done it for that length of time with people, it would be hard to tell if the music really represents you, or you’ve become this other thing, or it sort of becomes what you are and what you do.

The piece you wrote for tQ on Ken Russell mentioned an original drummer called Arthur Lager that I’d not heard of before.

JJ: His actual name is Nick Coombe. He was living in the next building of bedsits when I first moved to London, in Earls Court, and he somehow knew Mike Delanian, the original bass player. [We] went ’round to his bedsit and it stank of Super 8, it was so brilliant – he’d been making these amazing films in there on his own, these fantasias peopled by Barbie dolls and stuff – all stop motion on Super 8. They were such great films and, after he stopped playing with us, he carried on making Super 8 films but he changed his name to Arthur Lager. All of that was definitely an early part of Gallon Drunk. I’d been to school with Mike and he’d introduced me to Nick, and I’d been in a band with Joe [Byfield] out near Guildford [Johnstons’ home town] and he was the singer and then he happened to have some maracas so he became the maraca player and that was the line-up.

At one time it was just you and Mike wasn’t it?

JJ: Yeah, it was, ’cause he lived in Earls Court [too] but he had a bigger place and he had one of those giant 80s tape-to-tape machines and we used to try and do demos on that cause we couldn’t afford to go to studio, so it basically started like that. Through a couple of favours we got into a studio and recorded just the two of us and then eventually we thought, "We’ve got to try and do this live" and asked Joe and Nick.

So, did Gallon Drunk start before you reached London or was it a symptom of moving to London perhaps?

JJ: Possibly the latter, I’d played in a band outside London as I said with Joe, and what became Gallon Drunk definitely started once I’d moved up to town. I moved to London ostensibly to go to King’s College to study philosophy for a degree. I lasted one year and then drifted off into East Ham for several years [laughs]. Gradually we started doing music, but, funnily enough, at exactly the same time, Ian White was at King’s College doing classics and Latin or something, and he lasted one year as well. He also knew no one at the university, we were there at exactly the same time and we were both asked to leave at exactly the same time – we didn’t know one another –you know we’d been in the band together for several years and he said he’d been to King’s College and I was like "Christ, you were there at the same time?" and [he] was thrown out at the same time for the same reasons as me!

Looking at your chronology, there seemed to be two long periods where Gallon Drunk weren’t around [the decade spanning 1997 to 2007 saw just two albums, Fire Music and a soundtrack to a Greek film, Black Milk, released]. At the time I wondered whether you had packed it in?

JJ: We were still playing and touring abroad but a) we didn’t have a record company, and b) we were doing other things: in the early 2000s I joined the Bad Seeds so was very busy, there was so much touring with that, and then straight after that we did The Rotten Mile, which was so much better, I mean Black Milk‘s not really an album in my mind, but when we did The Rotten Mile it really felt like this is it again – really, really excited again.

Shortly after The Rotten Mile I was surprised to find you had joined Faust.

JJ: I think everyone was – I think Faust were surprised I joined Faust! I was playing with Mick Harvey somewhere and I got this call saying, "Can you get to Bristol tomorrow?" It was the end of the tour I was on and so I flew back and went to Bristol straight from the airport. [Having] never met them before, [I had a] fairly hazy comprehension of Faust as I think probably anyone has, probably they’ve got a pretty hazy comprehension of Faust! I turned up there and I was handed a set list that was all these drawings Jean-Hervé [Peron], the bass player, had done and I was like, "Okay, I don’t know what I’m doing with this." [laughs]

Like charts?

JJ: Not even charts, some of it was shapes, some of it scribblings – just mad stuff.

But it was intended as a score of sorts?

JJ: Yeah, absolutely, either to get inspiration from or somehow follow it. [Jean-Hervé]’d be going, "Leave holes, just leave holes!" They gave me a Farfisa organ to play but it didn’t even have a plug on it [laughs] so I was playing the guitar and it was the most mad, free, full-on, lovely, beautiful, crazy noise and I loved it! I ended up doing the rest of the tour and joining the band and then regularly going to the festival [Avantgarde Festival in Schiphorst, Germany] they have at Jean-Hervé’s wife’s farm every year for six years. It was through that that I met Johann, because Faust were rehearsing in [his] studio and ended up recording a record there. [Johann] came to the festival and Gallon Drunk were playing as a three piece and went, "Oh I’d love to record you in my studio," and we were thinking, "Does that mean it’s free? Has he signed us? We don’t really understand…" We were all too awkward and English and polite to actually ask him, so we ended up going in the studio [thinking], "Should we ask him now? What’s happening?" So we recorded the record all on a bit of a handshake – just this fantastic attitude, a lovely way to start working with someone.

Looking at the dates for the upcoming tour – it’s pretty relentless – you don’t get many days off.

JJ: Yeah, it’s ridiculous, it’s four weeks and we’ve got a day-off the second day [laughs] and then there’s nothing, we’ve filled in the gaps now. We’re playing Vienna, [then] have a day-off, then playing somewhere in the Czech Republic and then it’s non-stop.

While on tour are you with the rest of the band during the day or do you meet up of an evening? ‘Cause otherwise that’s a long time to be with someone.

JJ: Well most of the time we’re driving and an unwritten thing with us is there’s never any, any, any music in the van at all. We all sit there reading – that is so peaceful, it’s like going on holiday – I take a big pile of books with me – so, we’re all with one another pretty much the whole time and it’s just not a problem, it’s a pleasure.

So what books are you planning on taking?

JJ: Well, I don’t know, if Hilary Mantel would finish the last book [in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy], then I’d take that, but, not sure yet. I would like to read some more Ian McEwan.

Finally, what are your plans beyond the tour?

JJ: Well, I don’t know if we’ll go back into the studio this year, but, it would be great if we did. It will certainly be the end of this year/early next year when we start another one, but then that means it’ll be about nine months after that until it comes out. I think the last three records and From The Heart Of Town are the strongest ones, easily. And I think playing this record live will definitely suggest somewhere to go [next] ’cause they’re all going to get hugely extended these tracks – I can’t wait. And, like I said, we were just rehearsing and it sounded bloody brilliant – really, really exciting!