"Listen. The greatest feeling I ever had in my life – with my clothes on – was when I first heard Diz and Bird together in St. Louis, Missouri, back in 1944". So begins Miles Davis’ riveting, nakedly truthful autobiography, first published in 1989, making it a quarter of a century old this year. I finally got round to reading this classic confessional last month, and found it to be not merely be an electrifying autobiography, but, to my mind, one of the greatest books in the American lit canon, right up there with William Burroughs’ Junky, Jack Kerouac’s On The Road and Charles Bukowski’s Post Office. Of course, it’s highly likely Davis’ innovative music served as a muse for those brilliant writers. In terms of his character, Davis shared plenty in common with them: he was a radical artist who kicked out against the establishment, wrestled with heroin addiction and bouts of insanity, and harboured a macho tendency to abuse some of the women in his life. Moreover, much like Bukowski and Burroughs, Davis wasn’t shy of hiding away all the gritty details of his personal life, often coming off as an unapologetically unsavoury brute in some passages.

But this is a man who, in his own words, "changed music four or five times". Not just a giant of jazz, but a giant of culture, too. Along with his be-bop heroes like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, Davis empowered many black people with his music, arguably opening up new avenues for youths who previously felt invisible.

Whoever you are, artist or not, there’s plenty to learn about life from his incredibly turbulent story. Lessons come thick and fast on originality, self determination, standing up for political rights and style. Though his personality was dogged with paradoxes, Miles Davis was a giant on whose shoulders most other musicians stood. Suitably, this month’s installment of this column will begin with a live review of jazz luminary, Ahmad Jamal, whose swayingly melodic style had a huge impact on Davis’s modal music.

Ahmad Jamal – Royal Festival Hall, Southbank Centre

Monday 27 January

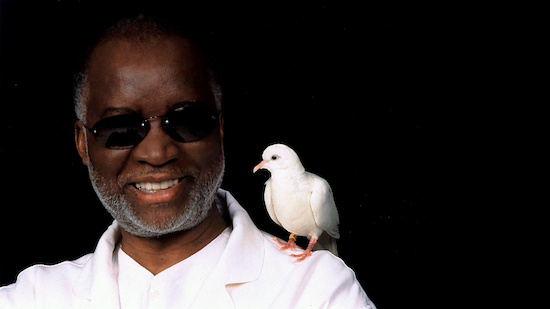

Beaming with a sagacious smile, Ahmad Jamal shuffled elfishly on stage before settling behind his piano; dressed in a two-sizes-too-big grey suit, the octogenarian luminary cut a figure like a ‘jazz’ Yoda. Appropriately equipped with deceptive mental agility and ninja-like acrobatics in the finger department, Jamal, who’s currently riding high on a second wave of stardom, filled the Royal Festival Hall with jazz’s cool, zen-attuned life force.

Decorated with plentiful accolades – including appointment as Duke Ellington Fellow at Yale University and recipient of the Jazz FM Lifetime Achievement Award, not to mention the dozens of decades experience conjuring sublimely lyrical music – the Miles Davis-influencing bandleader clearly has very little left to prove to the world. No wonder, then, he adopted a casual attitude towards his playing, especially during the opening quarter of an hour, where for a minute or two he sat motionless, arms folded, allowing his rhythm section to limber up with a slick, funky backbeat. When he became animated, though, his hands seemed to somersault up and down the registers. Indeed, notwithstanding his benevolent, care-free appearance, at times Jamal went for the jugular, with volleys of thunderous left-hand chugs and sharp, one-note attacks. This arresting, flip-flop method (one minute he’s serne, the next rampageous) was at the heart of his whole performance, whether on the honeyed romance of ‘I’m In The Mood For Love’ or hard-rocking new track ‘Back To The Future’.

Jamal’s fellow band members (drummer Herlin Riley, bassist Reginald Veal and ex-Weather Report percussionist Manolo Badrena) ought to take a bow for their part played in the pianist’s current resurgence. They put fire under his gorgeously breezy compositions on his latest LP, Saturday Morning, and added modern-sounding meat to his playing at this engagement. Veal’s plush-sounding bass pulsated throughout, especially on his hand-drummed solo, and Riley’s off-the-cuff beats were supremely self-assured, almost danceable. Meanwhile, Manolo’s intricate weave of hand drums, raindrop chimes and bird calls seemed to suggest the entrancing power of a mandala.

Of course, an evening with an elderly superstar wouldn’t be complete without a streak of aged-legend eccentricity. However, the quirky behaviour didn’t come courtesy of Jamal, but Manolo, whose deep-throated, comically timed jungle voices in the lead up to the ethereal ‘Silver’ nearly had the pianist falling off his stool in bewilderment.

Despite being deep into his twilight years, Jamal (83) continues to light the way down his own path of self discovery with meditative power and ease – and he doesn’t care who knows it.

Mehliana – Taming The Dragon

(Nonesuch)

The duo set-up is currently the hot ticket in rock (see Drenge, Royal Blood, Black Keys and Deap Vally). In jazz, the twosome format is also widely celebrated (you only need to look to German label ACT’s current ‘Duo Art’ series for proof). But, in contrast to rock duos, jazz partnerships aren’t typically hellbent on crumbling a club’s masonry with distortion-powered velocity; indeed, they tend to be a quieter, more reflective breed. Not in Mehliana’s case. On Taming The Dragon (the title refers to dream logic and harnessing the power of menacing subconscious personalities), the Radiohead-covering pianist Brad Mehldau and deep-groove drummer Mark Guiliana splice hallucinogenic, synth-gnarled prog-rock with the Mehldau’s classically-imbued improv in a demoniac attempt to destroy barriers, physical and otherwise. If there’s any jazzer fit for the job, it’s Mehldau, who’s well acquainted with the annals of rock, having reassembled tunes by riff-wielding blockbusters like Black Sabbath, Alice In Chains and Nirvana.

In the last few months, the duo haven’t had a good run of critical success off the back of live performances promoting this album; some reviewers cited the duo’s supposed lack of direction and taste. But this fiery, slickly produced monster should silence those critics. For fans of Uri Caine’s Shelf-Life, Satelliti’s Transister and Carl Jung.

Pat Metheny Unity Group – Kin (<–>)

(Nonesuch)

Nigh on 60, with his latest offering Kin (<–>), his fourth recording in two years, Missouri-born guitar legend Pat Metheny continues to push music to the outer limits compositionally, texturally and harmonically. Meanwhile, some stuck-in-the-mud Metheny devotees may still be grumbling that the guitarist’s compositional integrity has taken a knock since the departure of long-standing Pat Metheny Group (probably the guitarist’s most popular assemblage, currently on indefinite hiatus) keyboardist and co-composer Lyle Mays, who hasn’t been in the picture since the PMG’s excellent 2005 epic, The Way Up. But recent Metheny tour-de-forces including the guitarist’s solo Orchestrion Project masterstroke and challenging John Zorn collaboration, Tap, should have gone some way in assuaging their concerns that Metheny’s music has taken a nosedive since Mays’ exit. But judging by Kin (<–>), crammed full of cinematic beauty and musicianly wanderlust, for Pat Metheny the only way is up.

Listening to this LP and the Unity Band’s self-titled 2012 debut, it’s plain that this set-up is more or less the Pat Metheny Group (especially in its latter-day formation) in all but name. Extensive, episodic song architecture? Check. Lengthy but tasteful solo excursions? Check. Hummable, get-up-and-go melodies? Yep, it’s all there. Plus, now more than ever, Metheny unashamedly embodies the role of musical magpie, flitting effortlessly between post-bop energy, smooth R&B sass, ‘world’ rhythms, cinematic moods, Reich-like melodiousness and hair-flailing anthemism. Indeed, even by Metheny’s typically adventurous standards, this is a wonderfully tangential recording, all kept cohesive by his elegant, flowing ribbons of electric, acoustic and synth guitar.

Go Go Penguin – v2.0

(Gondwana)

Depending on your disposition, piano trio Go Go Penguin have one of the best or worst band names in history. However, the breakbeat-goes-classical jazz-rock of their 2012 debut, Fanfares, released on trumpeter/composer Matthew Halsall hip Gondwana label, didn’t appear to polarise the jazz masses. Indeed, most commentators and fans got behind that startling fresh and danceable record, a heady concoction of E.S.T-like pianistic lyricism, Squarepusher-mimicking beats and rain-streaked urban streets. Whatever your opinion of their name, though, the band audaciously matched its quirky appeal with bold modern jazz anthems.

The young Mancunian trio, now featuring the versatile bassist Nick Blacka, who replaced founding member Grant Russell after he left to pursue other projects, expand and heighten that template on v2.0. ‘Garden Dog Barbecue’ is a twisting-and-turning example of what the band excel at: activating both the head and feet with skittering beats and cascades of rippling, classically-informed piano riffs. Meanwhile, ‘One Percent’s’ interlocking, staccato grooves will wrong-foot anyone attempting to dance to it, due to the skipping-CD effect of its coda. It’s not all high-octane virtuosity. Ghostly ballad ‘The Letter’ was recorded in total darkness, and it shows, via haunting keys and dusky bass. v2.0 may be a reboot of their debut, but Go Go Penguin continue to stretch the piano-trio formula into the future.

Iiro Rantala – Anyone With A Heart

(ACT)

Though he’s Finland’s best-known pianist and a popular presenter on national TV, Iiro Rantala isn’t flashing up on many radars outside his country. That’s a shame. His graceful compositions run deep with palpable emotion and compositional flawlessness. His precise piano lines contain shades of Bill Evans’ human fragility. The late-lamented Swedish pianist Esbjorn Svensson’s spirit lives on in his harmonies. I’m aware I’m mentioning heavy hitters here, but in the case of this inventive composer, the connections are wholly justified.

Anyone With A Heart’s gushing liners read like quotes from Dalai Lama’s Book Of Wisdom. "The things that have true meaning in life come from the heart. I cannot imagine a more beautiful thing in life than love, love comes straight from the heart", muses Rantala. Fittingly, this classical chamber trio-esque song cycle beams with warmth and simple sincerity, all gilded with a certain romantic melancholy. The blissful atmosphere is heightened by Polish violinist Adam Baldych’s and Austrian cellist Asja Valcic’s pizzicato reveries on opener ‘Karma’ and ‘A Little Jazz Tune’, on which Baldych’s plucked violin briefly fools you into thinking it’s a classical guitar being stroked high up the neck. Much like Bristol’s excellent Three Cane Whale, Rantala occupies an acoustic-embracing space where spirited experimentalism and minimalism are paired with fragments of traditional themes.