Depending on your perspective, or perhaps even on your mood, the career of Gang Starr can be seen either as an exemplary and almost unblemished story of the ultimate in hip hop success, or a tragedy in which a talented emcee goes to his grave without ever receiving his just dues. At yet other times – perhaps most of the time – the Gang Starr saga is both at once. And Hard To Earn, the duo’s fourth LP, is both its pivotal moment and just another typical chapter in a history that oscillates wildly between those two poles.

Bostonian Guru and Houston native DJ Premier were always an unlikely pair to achieve golden-age-icon status. The cerebral, college-educated wordsmith and the taciturn beat-maker supreme weren’t boyhood friends who’d run the same streets and turned life’s lessons into art: they were introduced by staff at a record label and their initial collaborations were conducted, in those pre-internet days, by sending cassettes to each other through the post. Unusually among the classic-rap fraternity, their debut album, No More Mr Nice Guy, remains widely and understandably overlooked. There are moments of transcendence, particularly the declarative mission statement ‘Words I Manifest’, where Guru’s rhymes and Primo’s looping of Charlie Parker’s ‘Night In Tunisia’ end up setting out a stall for what was to follow. And there’s ‘Jazz Music’, of which more in a moment.

The duo’s acknowledged masterpiece came next, with the 1991 release Step In The Arena, its title, its appearance on a different (major) label, and the pair’s restyled visual image emphasising that it was so much of a new beginning as to more or less validate the view that the debut didn’t really count. Premier had arrived at what was to become his signature sound – chopped-up drums, melodic samples often drawn from early ’70s jazz funk, and choruses usually created by taking someone else’s rap record and scratching a phrase into a new context. Guru more than played his part, his slurry baritone a unique instrument, his lyrics inspired by and investigative of the key themes the pair’s records would return to again and again: street life, hip hop and its codes of honour, wordplay for its own sake, and respect – in particular, the acquisition, retention and protection thereof.

The problems began as backhanded compliments. The second LP’s sound and the palette of samples Premier painted with were much admired, and brought the album plenty of attention from outside the still small hip hop world; but they were tagged as "jazz-rap", the implication and inference being that this was a group somehow more concerned with making music to be appreciated by an intellectual elite (rightly or wrongly, this is what any invocation of jazz in the early ’90s routinely stood for) than in making hip hop music that the genre’s core fan base would be interested in. The intelligentsia claimed Gang Starr for itself, some of the praise unconsciously fostering the condescending notion that intelligent rappers interested in jazz couldn’t possibly be the sort of thing the genre’s usual fans would take notice of.

To be fair, the "jazz-rap" tag was at least partly of the duo’s own making. On No More Mr Nice Guy they’d offered a hymn to jazz in the shape of ‘Jazz Music’, a freeform and idiosyncratic weave through the genre’s history based around samples of Ramsey Lewis’s version of the Minnie Riperton classic ‘Les Fleurs’. Spike Lee heard it, and/or saw the ‘Manifest’ video, depending which story you prefer, while working on Mo’ Better Blues; thinking something along the same lines might fit the bill for the soundtrack, he suggested Guru try rapping a history-of-jazz poem written by journalist and screenwriter Lolis Eric Elie (who later worked on the TV series Tremé). Things didn’t quite work out so simply – Guru took elements of Elie’s poem and added new lyrics he’d written himself – but the resulting ‘Jazz Thing’ got Gang Starr noticed. Premier has credited the track with earning them the deal with Chrysalis/EMI that funded the rest of their career. It also indelibly inked the duo with the jazz-rap label, even though, after the opening montage of jazz clips, and despite the involvement of Branford Marsalis and Terence Blanchard, the main riff that pulses throughout the song came from a Kool and the Gang sample.

So the stage was set for misunderstandings and misinterpretations, and their inevitable corollary – commercial underachievement. For the next decade, the record industry and the music media managed to fail to get their heads around what Gang Starr were about, the former appearing to push the group towards making music that sounded more like whatever was selling at that time, the latter seeming to get upset that the pedestal they’d erected for the band wasn’t one Guru and Premier ever sought to alight on, nor felt comfortable enough atop to sit there for very long in the first place. After the superb Daily Operation – arguably (very arguably; all their records are pretty great) their best LP – was released to widespread indifference in 1992, the parts of Hard to Earn that remain somewhat hard to like do at least make some kind of sense.

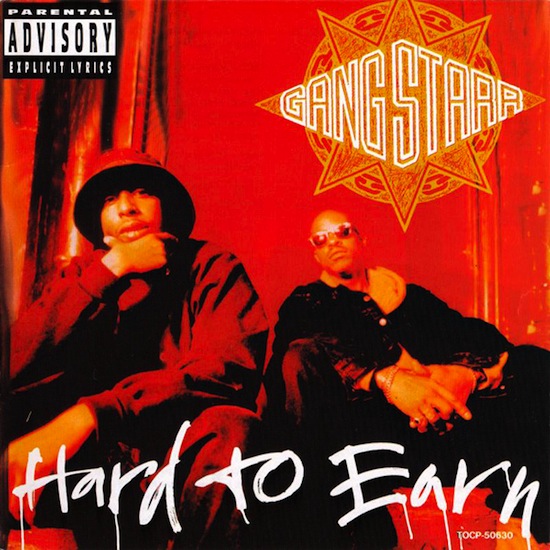

This was the era of gangsta rap, not Gang Starr rap – so the mobbed-up approach, with a proliferation of guest vocalists and a pervasive undercurrent of machismo bluster, felt like it was just what the audiences would expect. So too the depressing litany of female characters who make brief cameos in Guru’s lyrics, all of whom – with the exception of the aunt who rents him a room in the first verse of ‘The Planet’ – are skeezers, hos, scheming money-grabbers or just plain bitches. Ironically, for a group who, perhaps more than any other in hip hop’s history, remain synonymous with staying true to the music’s core values, this is the point in the narrative where they started to allow themselves to be influenced by what was going on elsewhere. The music remained singular, the style and approach distinctive: but they’d been around a while and hadn’t had hits, had seen other far-less-talented rappers streak past out of nowhere to platinum sales and international stardom, and there’s a sense here of Gang Starr wanting to get themselves a bit of that. You don’t glean that this was a series of observations drawn from a life where women played this almost sub-human role; it feels like Guru talks this shit because he thinks it’s what people want to hear from a hip hop artist in the nine-fo’. Which, in its own way, almost makes it worse. Especially given the failure of the gambit, if such it was: he dumbed down for his audience but the group, once again, failed to double its dollars.

The fog of unpleasantness this pointless and entirely avoidable nonsense lends the record is doubly unfortunate, because most of Hard to Earn is excellent. Premier had reached the absolute top of his game after spending the time since the last Gang Starr album quietly building a reputation as perhaps the quintessential hip-hop producer. And Guru, who had inaugurated his Jazzmatazz side-project franchise the year before (some press ads for this album included the line "You thought they’d broken up", so prolific had the pair been individually over the preceding 18 months), never sounded better vocally than he does here. The opener, ‘Alongwaytogo’, is jaw-dropping – Premier constructing a track that manages the considerable feat of sounding both panicked and slouchy, while Guru’s rhymes appear to have been delivered under severe duress by a man suffering from a rotten head cold. It sounds at once exactly like Gang Starr, yet totally different – the hooks, scratched-up portions of A Tribe Called Quest’s ‘Check The Rhime’, helping set out the album’s key theme as Guru’s lyrical jewels bedazzle as he speaks about "the counterfeit/unlegit type of people/the cellophane ones, the ones that you can see through," and how his writing is "so precise my insight will take flight in the night."

Most of the rest of the first half is similarly unimpeachable. ‘Code of the Streets’ is the pair at their most vivid, Premier etching a piece of ultra-hard hip hop from the unlikeliest of sources (a jazz cover by Monk Higgins of the 1960s pop song ‘Little Green Apples’, best known in a version by Roger Miller) while Guru isn’t content to simply relate tales from the margins, he’s in there looking at how poverty and a lack of options conspire to lure people into crime and asking pertinent questions. ‘Speak Ya Clout’ follows Daily Operation‘s inaugural Gang Starr Foundation excursion with another cut from the same cloth, Guru, Lil’ Dap and the reliably excellent Jeru the Damaja each getting to rhyme over a different beat. ‘Brainstorm’s tale of lyrical combat ends in a torture scene that’s so violent the track fades out, like that moment in Reservoir Dogs where the camera can’t stand to watch the blade touching the ear so it pans away to spare us the pain. Even ‘Tons O’ Guns’ belies its simplistic title to deliver a cogent analysis of some little-reported sides of America’s evergreen gun-ownership debate.

A word or two on Premier and sampling. This wasn’t the first record he made that hit such heights as consistently, but there may be few albums in even his remarkable discography that show such a sustained and singular flair not just for the practical mundanities of hip-hop music-making, but in hearing in other people’s music things its makers surely cannot have intended or imagined. The two examples that stand out are ‘The Planet’, Guru’s paean to his adopted home of Brooklyn, which is set to a kind of broken-down reggae beat, sleazy and off-kilter, beguilingly precise in its insistence on being just that little bit wobbly; and ‘Mass Appeal’, the album’s first single, the elusive source of which’s hypnotic organ loop became a cause célèbre among the small but obsessive band of beat-fiends who populated the Crates List, an email network for the similarly afflicted that took up a worryingly dominant part of the lives of more than a few of us in the closing years of the 20th Century.

There were two big mysteries the denizens of the Crates List wanted to solve: the identity of the main loop from Mobb Deep’s ‘Shook Ones Pt II’ (an elaborate, multi-sample, backwards/distorted/treated solution has since been proposed, though some – your correspondent included – remain unconvinced), and where the hell Primo got ‘Mass Appeal’ from. The ‘…Planet’ loop held no such intrigue – it’s credited on the Hard to Earn sleeve, which presumably means its author, Steve Davis (not the snooker player, nor the Californian drummer, or the bassist who played with McCoy Tyner, but the Nashville songwriter who, these days, is less ambiguously known as Stephen Allen Davis) got paid. ‘Mass Appeal’ turned out to come from a 1979 album by the guitarist Vic Juris, but the answer begged an even bigger question. OK: so we know where it comes from – but how on earth did Premier even hear the germ of ‘Mass Appeal’ in that tiny part of ‘Horizon Drive’, which appears for less than two seconds at a considerably faster speed than it does in the Gang Starr track, and when it does so is conveying an entirely different mood?

These were loops that required a fair bit of finding even once you’d stumbled upon the track – both samples come from the halfway points, roughly, of each original tune. Not for Primo the simple kleptomaniac pleasures of lifting an opening drum loop or melodic swirl (not that he was averse to doing that, when the mood took him: evidence abounds across his discography, though he’d perfected the art on Step In The Arena – ‘Check The Technique’ repopularised Marlena Shaw’s reading of ‘California Soul’ a decade before advertising execs and chill out clubbers took it to their hearts, and cemented Premier’s love affair with Charles Stepney’s orchestrations by ensuring both the first two Gang Starr albums lifted from his symphonic pop meisterwerks). And why did he light upon these two albums, which remain obscure and out of print even today, when so much of the 1970s has been reappraised, re-evaluated and re-released?

Here’s a guess, on one of them at least: the Davis LP, ‘Music’, has a personnel list on the back sleeve that includes one George Clinton. Chances are it isn’t that George Clinton – the captain of the Mothership, as prolific and eclectic as he undoubtedly was and remains, was probably a bit too busy in 1970 to drop in on a session in Nashville run by a songwriter with virtually no profile who was recording for a label with which P-Funk had no formal connection. The smart money says Premier saw the record in some bargain bin somewhere, noticed the credit and the year of release, expected to find something sampleable, and picked it up. Confronted with one of the strangest, most musically wide-ranging of LPs – Davis appears to have conceived it as a showcase for songwriting that spanned every genre imaginable, sometimes more than two in the same song; it remains, as one of the very few pieces of writing anywhere online about the record describes it as "one of the best records I’ve heard by a guy I’ve never heard of" – he refused to admit defeat and, burying himself in its complexity, he dug out a chunk of cherishable musical weirdness and built a Gang Starr track around it. The man’s a genius. As for the Juris, I’m not even going to hazard a guess.

For all the first half’s excellence, though, the record tails off toward the end. One of Gang Starr’s chief sources of appeal was always their self-contained nature: like fellow golden-agers such as EPMD and Public Enemy, they came along when being a band meant the same in hip-hop as outside it; you created your music yourself, without routine and extensive recourse to outside assistance. A credit as a producer of a hip hop record tended then – and still tends now – to mean something different to production in pop, jazz or rock: it’s not just about finessing the sound and recording it well, it also means you compose, arrange and orchestrate the music. The day production duties were ceded primarily to musicians outside the core grouping around the artist whose name appeared on the package was the day hip hop stopped living in the land of artists and albums and concentrated, cohesive, complete creative thoughts, and entered the world of A&R-led experiments in brand-building and marketing. In some respects, then, hip hop now is a throwback to an earlier era, when label execs would find songs for singers to sing, and assemble teams of musicians and studio technicians to help them put collections of those songs together for sale in a single LP package. In another sense, something valuable and creatively important was lost. To their credit, Gang Starr never succumbed to the temptation to use outside producers – but they did bow to the growing commercial imperative to rope in a host of guest rappers here, diluting the impact of the second half of the record and adding little in return.

True, this wasn’t the star-studded roll call of cameos that turned all too many hip hop albums into de facto compilations in later years. This was an experiment in highlighting friends and associates, part of the patchily effective Gang Starr Foundation, and thus similar in conception to EPMD’s use of their own albums as leg-ups to their Hit Squad mates, in whom Erick and Parrish had money as well as friendship invested. The difference is that – with the exception of Jeru, who made two (Premier-produced) albums in the twilight of the golden age that remain among the period’s highlights, and who only gets one verse here – Gang Starr’s mates just weren’t much cop. Lil’ Dap, Melachi the Nutcracker and Big Shug’s failures to forge lengthy careers come as little surprise (the latter’s contribution to a later guest-strewn Gang Starr classic, ‘The Militia’, notwithstanding), as they lack the presence or the promise to do much more than distract. They add nothing of real note to Hard to Earn.

There is one collaboration here that does hit the spot, though ‘DWYCK’s impact was lessened for devotees of the band (which, almost by definition, meant all of their fan base: Gang Starr never meant much outside a circle of listeners for whom everything they recorded was pounced upon and pored over as the hip hop equivalent of holy writ) by dint of having been out on a b-side for almost two years before Hard To Earn was released. The song, its title apparently a Guru-created acronym standing for "Do What You Can Kid", pitches the Bostonian’s languid flow between two emcees whose vocals sound as though they sit almost at opposite ends of Guru’s stylistic scale. Greg Nice is all bounce and pep, his lyrical jabs and darts full of life, and he’s clearly having fun; Smooth B shows that Snoop wasn’t the first to give rap a sing-songy lilt, and provides abundant evidence that a mellifluous flow doesn’t mean an emcee couldn’t pack plenty of lyrical punch. Nice & Smooth sandwich Guru’s verse, but – whether he realised at the time or accepted it afterwards or not – they also overshadow him, and have the bad manners to do appear to enjoy doing their host the discourtesy of out-rapping him on his own track.

The key is in what one of the wags over at RapGenius calls "possibly the most enigmatic line in the history of Hip Hop" – the bit where Guru says, a propos of not a very great deal, "Lemonade was a popular drink and it still is." Tongues presumably firmly in cheek, the RG brains trust argue that in that line, Guru’s making a case for ignoring the validation commercial success appears to convey, and advocating that rappers and hip hop fans alike should stick to what they know to be of quality, regardless of the passing fads and trends that dictate success in the marketplace. They may have a point, and if that’s the intention, it certainly chimes with the album’s key lyrical preoccupation, the theme outlined in its title, and the subject gone into in depth on ‘Mass Appeal’. However, this surely stretches the point beyond its elastic limits. It’s clear, even on hearing the next line for the very first time ("I get more props and stunts than Bruce Willis"), that Guru, having come up with that clever set of double meanings – as succinct and beautifully crafted an encapsulation of the art of the emcee as one can imagine putting into nine syllables – was in need of something to rhyme with the Die Hard star’s surname, and found himself scrabbling around to shoehorn that "still is" into the preceding line. It works as humour, as a kind of lyrical slapstick, but only if we accept it as a freestyler’s equivalent of waving the white flag – admitting that they can’t come up with anything better right at that moment. By comparison, Smooth B’s galumphing "oesophagus"/" rhinoceros" couplet is almost balletic in its nimbleness and poise.

After ‘DWYCK’, which sits just before the end of Side One on the originally conceived single-vinyl/cassette version of the album, the record runs out of steam. ‘Suckas Need Bodyguards’ was a late replacement for ‘Doe In Advance’, yanked off the album shortly before release due to sample-clearance problems; ‘Mostly The Voice’ has one interesting thing to say but spins it out into a song when a verse would’ve been pushing it; and ‘Blowin’ Up The Spot’ wastes a great Premier track on one of Guru’s most formulaic verses. But there’s still much here to love, rather more to admire, and, despite the often ugly and always deeply ironic attempts to court a lowest-common-denominator acceptance through inclusion of lyrics that Guru should have known better than to ever dream up never mind record, it remains up there, alongside another three of this remarkably consistent group’s six LPs, as among their best work. Just another Gang Starr record, then – but Gang Starr were never just another hip hop group.