William S. Burroughs is like a speck of dirt in your carpet: once you start looking, you see him everywhere.

This year, the spectre of literature’s loosest cannon will loom as large as it has since his death in 1997 aged 83 (not a bad innings for a man who treated his insides like a trashcan for half a century) as readers mark the centenary year of his birth. As well as a new biography by Barry Miles and the re-release of the 1983 documentary Burroughs: The Movie, you can catch his gun-splatter paintings at The Photographer’s Gallery in London or head to Bloomington, Indiana, for a week-long academic jamboree under the banner The Burroughs Century.

Burroughs was indeed a man of the 20th Century – he was alive for most of it, after all – and his life and works form the very fabric of the counterculture, seeping into literature, painting, film, theatre and most of all music like a drop of acid on a sugar cube. Like Allen Ginsberg, he lived long enough to see the beats’ influence germinate and mutate through younger generations of writers, filmmakers and especially musicians, who borrowed freely from Burroughs’ grotesque imagery, sardonic humour, formal innovation, political subversion and relentless nihilism.

This cross-pollination between the arts, and particularly between music and literature, decelerated in tandem with Burroughs’ final years. The end of his life coincided not only with the waning of his influence on young musicians, but the waning of literature’s influence on music more broadly. In the 21st century, how often do you hear musicians talk about being inspired by books or poetry? With the occasional exception for science fiction writers, particularly the ever-more prescient work of J. G. Ballard, independent and underground musicians are now far less engaged with other artistic mediums, opting to stay safely inside music’s closed circuit of regurgitated genre experiments. That even applies to those who borrow most liberally from the music Burroughs inspired, like the countless bands who riff on post-punk’s style yet ignore its radical spirit.

That’s not the fault of our musicians, exactly – literature simply isn’t at the cutting edge of the arts in the 21st Century; the internet-addled alt lit trend spearheaded by writers like Tao Lin just isn’t comparable to the visceral, anti-establishment thrills presented by Naked Lunch in 1959. In the middle of the 20th Century, as modernism smashed its way into popular culture, literature was at the cutting edge; as alluring as bebop and the Beatles, as shocking as punk and no wave, and as radical as avant-gardists like Cage and Stockhausen. By the time Burroughs collaborated with Kurt Cobain on 1993’s The "Priest" They Called Him, ten minutes of spoken word set to grinding guitar scree, both were trading on the former’s countercultural capital, a throwback to radicalism against the creeping commercialisation of grunge.

After the accidental shooting of his wife in 1951 (a calamity that turned out to be the awful catalyst for his career, initiating what he called a “lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out”), Burroughs headed to Tangier in Morocco, where he wrote page after page of what would congeal into the book that made him America’s most notorious writer, Naked Lunch. Aided by the growing mythology around his queer-junky-outlaw persona, Burroughs became a beacon of the counterculture as it gathered pace into the 60s, idolised by young artists and musicians who brought him further fame and a wider readership. Lou Reed, a student of literature and a chronicler (and habitue) of New York’s bohemian underbelly, was one of Burroughs’ most obvious descendants, corrupting his sweet pop melodies with seductive visions of sadomasochism, sexual transgression and smacked-out oblivion. “Burroughs alone,” said Reed, “had the energy to explore the interior psyche without a filter.”

Both were drawn to unwholesome goings-on at the margins of society, documenting sex, drugs and unorthodox desires with an unflinching gaze, but though their taste for obscenity piqued the interest of readers and listeners, the intention was never simply shock or titillation. Underlying Burroughs’ obscenity was a constant, paranoiac fear of ‘the Man’, the sworn enemy of the counter-culture who symbolised corruption at the highest level; Reed, meanwhile, gave his subjects (the titular Candys, Carolines and Stephanies) an awkward dignity even while exposing their private fears and vices. Both writers could also be darkly comic, though actual laughs are few and far between – Burroughs with his absurd talking assholes, or Reed’s surreal and macabre short story ‘The Gift’ (as narrated on White Light/White Heat by John Cale).

Around the same time, Burroughs’ sticky way with a phrase gave Steely Dan their name, taken from the milk-spurting strap-on dildo in Naked Lunch, while across the ocean, The Soft Machine took theirs from the title of a 1961 novel, the first produced entirely with the cut-up technique. That process, invented by painter and writer Brion Gysin and introduced to Burroughs at the Beat Hotel in Paris, was used to sculpt the vast “word hoard” written in Tangier into three works known as the Nova Trilogy. By cutting typewritten pages into strips of just a few words, or taking two sheets and folding them over to make new sentences (the ‘fold-in’), Burroughs rearranged his text into unexpected, non-linear structures, thus releasing himself and the reader from the ‘control’ (a concept he feared above all) of words, and their ability to force us into conventional patterns of living. “You cannot will spontaneity,” he explained, “but you can introduce the unpredictable spontaneous factor with a pair of scissors.”

The literary cut-up has clear parallels in other arts, from collage and action painting to the aleatoric music of John Cage, one of Burroughs’ contemporaries. In the 60s Burroughs himself attempted to map the cut-up concept onto another medium with a reel-to-reel tape machine, splicing weather forecasts from the radio with snippets of gloomy news broadcasts about murder and war. The seemingly random results of this aleatory method also held something like an occult power to the deeply superstitious writer. “When you cut into the present,” he suggested, “the future leaks out”, a phrase that also manages to connect the cut-up to the history of sampling and the formal innovations of hip-hop and jungle, with DJs and producers scratching and chopping their way into the sound of the future.

The divinatory aspect of the cut-up process would surely have appealed to the young Genesis P-Orridge, who met Burroughs and Gysin in the early ’70s and communicated with them for several years, exchanging ideas on art and esoteric spirituality. Lyrics for Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV were manufactured with the cut-up technique, and Genesis eventually applied the concept to human flesh in the ‘pandrogeny’ project, in which s/he and h/er wife Lady Jaye Breyer P-Orridge (to use their chosen pronouns) literally cut up their bodies in an effort to become a single being, a mirror-image of each other.

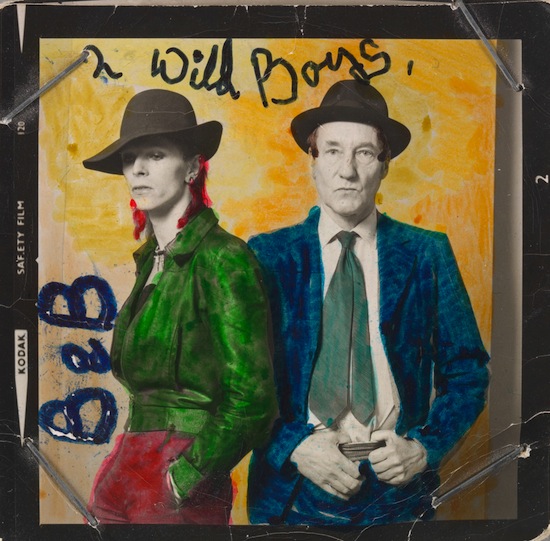

David Bowie, always alert to an avant-garde idea for his pot, was naturally one of Burroughs’ most high-profile fans. They met in 1974 (an encounter that was published in Rolling Stone), a few years after the publication of Wild Boys, from which Bowie had cribbed ideas for the look and story contained in The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. After reading Nova Express, a book from the cut-up trilogy, Bowie applied the method to his next album, Diamond Dogs, starting with ‘Sweet Thing’ (“If this trade is a curse then I’ll bless you / And turn to the crossroads of hamburgers”) and continuing for the rest of his career – with notable improvements to the final product. As Jon Savage points out, the approach helped to speed up Bowie’s writing as he experienced the pressure of expectation from his growing fame; it also suited his increasingly choppy mental state. Later he developed a computer program called the ‘Verbasiser’ to cut and reassemble sentences instantly, acting as an automated lyric dispenser.

As the ’70s rolled on, Burroughs’ fame grew to cult-like proportions, assisted by patronage from influential musicians like Reed and Bowie. His return to New York City in 1974 cemented his reputation as he came into contact with a younger generation of punks and avant-garde artists who idolised him, including the likes of Patti Smith and Mick Jagger, who would drop in at his windowless ‘Bunker’ on the Bowery. Burroughs himself wasn’t too keen on the music, preferring the more digestible work of older American songwriters like Hoagy Carmichael, but he dutifully appeared out and about in his role as an elder of the cutting edge scene. A steady ingestion of drugs and alcohol aided his mythologising as the ‘gentleman junky’, while his frequent speaking engagements became performances in their own right, the writer-turned-rock-star enthralling audiences with his colourful prose and solemn, gravestone-like delivery. Norman Mailer even complained that Burroughs only had to make a passing comment about the weather to get a belly laugh from his crowd.

The combination of highbrow literary ambition and lowest-of-the-lowbrow fixations (the dildos, hangings, ejaculation and the rest) across his oeuvre meant Burroughs appealed to musicians across the spectrum, from avant-garde types drawn to his formal innovations down to the wannabe junkies and CBGB-dwelling dilettantes who mistook Naked Lunch for a user’s guide. From the former camp, performance artist Laurie Anderson was one of many musicians who recruited Burroughs’ famous voice for their own work with her 1981 collaborative album with the poet John Giorno, You’re The Guy I Want To Share My Money With. She later used his voice again to update her famous tape-bow violin experiments, this time replacing analogue tape with MIDI audio samples.

A similarly experimental project came at the end of that decade with The Black Rider, a theatrical ‘musical fable’ for which Burroughs provided the story, based on a German folktale, with Tom Waits writing the music and lyrics and avant-garde director Robert Wilson taking the helm. Though the eventual album release featured just one brief appearance from Burroughs, in the sleeve notes Waits played up the writer’s role in the production, saying Burroughs provided “the branch this bundle would swing from. His cut-up text and open process of finding a language for this story became a river of words for me to draw from.”

Meanwhile, the semi-autobiographical content of the novels and the growing aura around Burroughs himself provided ample fodder for aspiring punks and rebels seduced by the writer’s apparent freedom from responsibility. Much like the rock stars who admired him, Burroughs led an itinerant lifestyle, always moving and travelling (and occasionally running from the law) with no particular place to call home. Despite several run-ins with the police (including when he failed to report the murder of his old friend David Kammerer at the hand of Lucien Carr, as narrated in the recent film Kill Your Darlings), Burroughs somehow slipped out of the authorities’ grasp continually, even after being convicted in absentia of shooting his wife.

The selfish, insular world of the junky, who constantly places his bodily needs above the wellbeing of those around him, is only a more concentrated version of the anti-authoritarian and distinctly individualistic flavour of New York’s punk, which even spawned a few rock and roll Republicans like the Reagan-supporting Johnny Ramone and Tea Party turncoat Maureen Tucker. (This was in contrast to British punk, which tended to couple its distaste for authority with an assertion of socialist, anarchist and anti-fascist ideals.) For Burroughs and for the young generation of musicians inspired by him, the enemy was control in all its forms, an ethos that trickled into the 80s with hardcore’s rejection of corporate rock and the major label system (though one could argue that hardcore’s fierce politics and sanctimonious attitude towards drink and drugs produced a scene that was just as ‘policed’ than the mainstream they opposed).

Despite Burroughs’ willingness to mingle with the musicians who idolised him, there’s little to suggest he took much of an interest in the art they were creating. That’s hardly a surprise – he was already tipping into middle-age when rock and roll arrived, and much preferred the jazz he’d grown up with (the same goes for his sartorial tastes, which pretty much began and ended with a three-piece suit). He liked pre-war jazz like Lester Young and Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five, as well as Viennese waltzes and Moroccan music. Short on cash once, he picked up a commission from Crawdaddy to interview Jimmy Page, but found little to say about the Led Zeppelin concert he attended, drily noting that “the performers were doing their best, and it was very good.” (He and Page got along just fine once they discovered their shared interest in magic, however). In his diary he even admitted “not knowing much about music” after observing Paul McCartney in the studio working on ‘Eleanor Rigby’, remarking only that the Beatle was a “nice-looking young man, hardworking.”

Yet throughout the 80s and 90s – well into his old age – he collaborated frequently with these noisy young musicians, adding a soupçon of outlaw glamour to whichever project he lent his hypnotic speaking voice. Among them was Bill Laswell’s band Material, whose 1989 album Seven Souls explored uncharted territory between funk, hip hop and Middle Eastern music and placed Burroughs’ voice as one bouncy sample among many, though his contribution, as usual, involved a reading from his one of his own novels (The Western Lands). Similarly, the collaborative album with The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, Spare Ass Annie And Other Tales, used Burroughs’ voice as a rhythmic tool, folding it around the lolloping drum breaks, making it seem as though he was almost rapping in time with the beat. Also appearing in this period was Dead City Radio, an album under Burroughs’ own name that brought in John Cale, Sonic Youth, Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen, Blondie’s Chris Stein and saxophonist Lenny Pickett to provide musical accompaniment for readings, including the well-known, gruesomely sardonic ‘A Thanksgiving Prayer’. Though less focused than the albums with Material and the Disposable Heroes, it’s one of his most accessible – and even fun – musical releases.

Dead City Radio was in fact Burroughs’ second album, following a spoken word release in 1965 which featured extracts from Naked Lunch, Nova Express and The Soft Machine. Call Me Burroughs was a minor hit in fashionable circles, according to biographer Barry Miles, who claims Paul McCartney favoured it for stoned late-night listening, and in fact owned it before he read Naked Lunch. (Burroughs was later to be immortalised on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s, squeezed in next to Marilyn Monroe).

One distinctly off-the-wall collaboration came about in 1992 when Burroughs joined the inimitable Al Jourgensen on Ministry’s single ‘Just One Fix’ (no prizes for guessing what that one’s about). As fellow addict Jourgensen recalled, he dropped in on the writer’s home in Lawrence, Kansas, before the video shoot: “[Burroughs] opens the door and the first thing he said was, ‘Are you holding?’” With only enough heroin for themselves, Jourgensen and his friend drove all the way back to Kansas City to score before being allowed back in, where they watched Burroughs pull out “this 1950s pulp fiction kind of tool belt with needles in it, old school, huge needles.” After shooting up, Jourgensen noticed a letter on the desk clearly marked from the White House. “So I go, ‘Do you mind if I open it?’ He’s like, ‘Man, I don’t care’. So I open it and there’s a letter from President Bill Clinton asking him to speak at the White House. And the only thing he said was, ‘Who’s president nowadays?’ He didn’t know.”

It’s hard to imagine what Burroughs made of his musical collaborators, particularly the abrasive, industrial gut-punch of Ministry, but it seems impossible that they were chosen at random. Burroughs used these collaborations as a conduit for his own work, like a cavalry of Trojan horses ready to infiltrate the corruptible youth. They were, you might say, a marketing tool – and they worked, helping his celebrity to grow steadily during his final decades. He must also have sensed that these artists’ intentions were, on various levels, similar to his own. The sonic extremes and bristling nihilism heard in Ministry and Sonic Youth, the cerebral experimentation of Laurie Anderson and Tom Waits, the loose, streetwise energy of Material and the Disposable Heroes – all of these acts had developed traits in common with the writer.

The legacy of industrial music, in particular, came full circle in the 90s as he met former Throbbing Gristle member Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson, whose own band Coil then recorded samples of Burroughs’ voice for their planned, but ultimately unreleased album Backwards (the samples are missing from their second attempt, 2008’s The New Backwards). Christopherson, who had directed the video for ‘Just One Fix’, recalled: “We asked him to recite certain key words and phrases for us. This material has a shamanic quality to it, really it is a magickal spell. This is where we connect with William; he describes the invisible world, he documents the hidden mechanisms. This is what we also seek out; the secret mechanisms, the occult, if you like, given that occult simply means hidden." Coil communicated with Burroughs for many years, receiving letters and Christmas cards from him until his death.

In Burroughs’ last years, Kurt Cobain came to visit him in Lawrence a little while after the release of their collaborative record. As biographer Charles R. Cross tells it, when Cobain drove away Burroughs remarked to his assistant, “There’s something wrong with that boy; he frowns for no good reason.” A few months later, Cobain was dead. The fact that Burroughs outlived Cobain, one of the last torchbearers of the counter-culture spirit that fuelled the punk rock lineage behind Nirvana, seems oddly symbolic; one the 20th century’s most influential writers had lasted longer than his own legacy.

In the 21st Century, Burroughs’ influence remains embedded in the lineage of musicians who admired him, a lineage that forms the DNA of so much of the most exciting music of the past 50 years. As digital technology works to flatten pop history, delivering us sounds from today or from a century ago in a instant, the youngest generation of listeners are closer than ever to stumbling across the visceral thrills of Naked Lunch as they discover the artists Burroughs influenced, who have in turn been canonised. He’s unavoidable for anyone with more than a passing interest in the work of Reed, Bowie, Sonic Youth, Laswell, industrial music, and indeed Ministry.

But since his death, no other writer has emerged to rival his dominance over the arts. For all the buzz around alt lit, it’s hard to imagine that literary niche having a profound impact, or much impact at all, on today’s musicians. The so-called ‘vaporwave’ sound and the digital dystopias of James Ferraro already feel far more powerful, and far more formally innovative, than anything literature can currently offer. It’s certainly rare to hear new artists citing Burroughs’ work, just as it’s rare to hear them talk about literature at all, preferring these days to keep their heads out of the clouds. Remember that when Klaxons wore their Burroughs and Ballard fandom on their sleeves, they were mocked, while the image of the nattily-dressed junky poet has been tarnished beyond repair by other regrettable characters. Likewise the very idea of singing words that mean something, or anything, has slipped out of fashion in recent years, just as that entire punk-rooted lineage seems to have ground to a halt, bereft of new ideas and cursed to recycle its own past.

Today we are, as the truism goes, more connected than ever – the perfect incubator for the widespread exchange of ideas. It’s what the counter-culture thinkers dreamed of (and helped to build in Silicon Valley). Yet it also feels like we’ve lost our dreams of radicalism, lost our belief in what art can do, or be, to us. There is no turning back the clock, Burroughs’ moment has passed. But as we reflect on his centenary and his remarkable influence on the 20th Century, and on the history of avant-garde and pop music, we should keep our own moment in mind and question why no one has emerged to take his place.