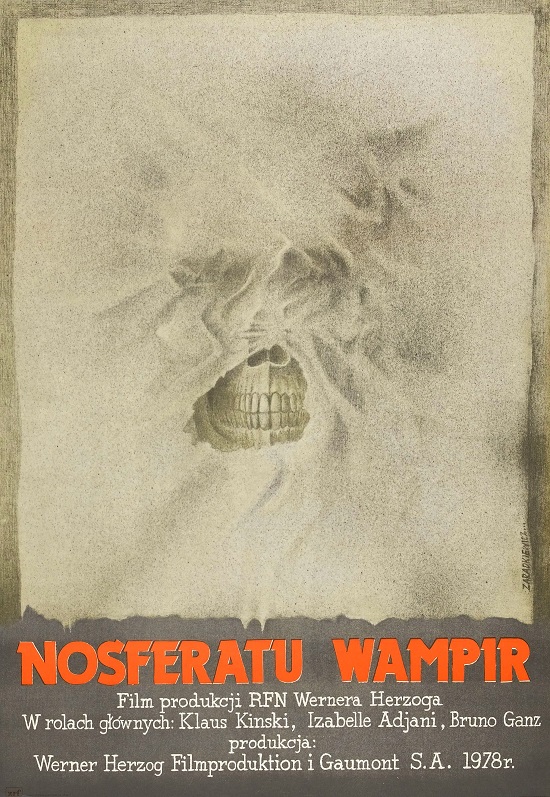

The BFI’s immense season Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film is open now, and the first strand, called ‘Monstrous’, places new releases of two classic Nosferatus at its heart . FW Murnau’s 1922 silent classic Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, (Nosferatu Eine Symphonie des Grauens), with Max Schreck as the vampire Count Orlok, is the earliest (surviving) film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, and it’s being rereleased at the same time as Werner Herzog’s 1979 retelling Nosferatu the Vampyre (Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht) , which stars Klaus Kinski as Dracula and Bruno Ganz and Isabelle Adjani as his victims, the Harkers.

Other films based on Stoker’s tale came in between, of course. There was Tod Browning’s beautiful, chiaroscuro Dracula in 1931, in which Bela Lugosi played a sophisticated, dapper Dracula quite different from Schreck’s animalistic fiend. The Hammer versions took this new, suave kind of vampire and ran with it, starting in 1958 when Terence Fisher’s Dracula first brought Christopher Lee’s seductive Count to the screen in full, melodramatic colour. (Incidentally, Jess Franco directed Lee in the role once too, in 1969’s Count Dracula, which also featured Kinski, this time as Renfield). Then there was the BBC’s haunting, faithful 1977 television adaptation (also included in the Gothic season) in which director Philip Saville backed away from Hammer’s lurid pulp fantasies and returned Dracula to his stranger, more poetic roots in Gothic literature.

When Werner Herzog made his Nosferatu, though, he went directly to Murnau for inspiration. In Herzog on Herzog, the director claims that, "I never thought of my film Nosferatu as being a remake. It stands on its own feet as an entirely new version… My Nosferatu has a different context, different figures and a somewhat different story." Perhaps Herzog’s distinction is philosophical; perhaps he is arguing that without the intention to completely re-shoot a film isn’t a remake. And the context of Europe in 1979 is inarguably different from that of 1922. Otherwise, though, his statement is a curious one; his Nosferatu echoes Murnau’s almost scene for scene, detail for detail, theme for theme

Herzog on Herzog goes on to state, "What I really sought to do was connect my Nosferatu with our true German cultural heritage, the silent films of the Weimar era and Murnau’s work in particular." His Nosferatu might, then, be trying to argue for a post-Hammer reappraisal of the way vampire films can explore profoundly complex thematic concerns, and doing this by returning attention to Murnau’s original contribution as something essentially German. If so, perhaps, it’s ultimately too personal a film, and too far-ranging and eclectic in its cultural borrowings, to really achieve this with any clarity. Viewed simply as a vampire film on its own, or as a statement of response to Murnau’s, or just as an example of Herzog’s characteristic lyricism, though, it is an absorbing and rewarding experience.

It feels like a very personal film, in any case. As Herzog puts it himself, "The images found in vampire films have a quality beyond our usual experiences in the cinema. For me, genre means an intensive, almost dreamlike stylisation on screen, and I feel the vampire genre is one of the richest and most fertile cinema has to offer. There is fantasy, hallucination, dreams and nightmares, visions, fear, and of course, mythology."

And indeed, both films are rich in imagery drawn from the landscapes of the preceding 150 years or so of Gothic literature – the romance of long journeys by horse and carriage through the misty mountains and charming meadows of central Europe, the rural idyll, and the labyrinthine, crumbling castle representing the mind and the horrors that lie within it. Both are concerned with the function of mythology, and why people tell stories of demons and ghosts and ‘the land of thieves and spectres’. Both concentrate on the Black Death, and the vampire, attended by hordes of rats, as a literal harbinger of plague. The Count in his castle is the symbol of corruption at the heart of society, and like a scapegoat, must be cast out by his subjects if the community is to survive. This is the aspect of the story that Herzog develops the most, adding scenes of a plague-ridden Wisborg degenerating into a kind of debauched, pastoral anarchy in which pigs wander the streets and townsfolk dance and dine al fresco in the main square under a gloomy, Turneresque sunset.

Most of the rest of the memorable imagery in Herzog’s film, though, is taken directly from Murnau’s. It reads like a collection of what meant the most to him – the first drop of blood spilt at the dinner table, the skeleton clock, the setting sun suddenly obscured by dark clouds behind a bleak mountain ridge, the coffins overflowing with rats, the dark-sailed ship alone on the waves, the wild-haired madman eating flies in his cell, the strange cemetery in the sand dunes. Herzog’s interpretations of these scenes are usually elaborations – lingering on the contrast between the desolate beach and the jagged mountains, for example, or his completely over the top use of ten thousand rats where Murnau had ten.

Both films, too, portray the vampire himself as rodentine, inhuman, white-faced and bald, with spider-like hands and bat-like ears. Schreck’s Orlok is a more otherworldly figure than Kinski’s Dracula, though. Schreck brings a crazed glee to the role, whereas Kinski plays Dracula with a terrible sadness. He is clearly other than human, but his yearning for humanity is deeply touching. Both versions have, of course, the underlying sexuality with which vampire myths are inextricably linked, although Kinski takes it much further in his tender yearning for both Jonathan and Lucy.

Where Herzog’s aesthetic departs from Murnau’s is the heavy influence of British Victorian paintings. He keeps the fictional German setting and this release uses the German dialogue dub, described by Herzog as "the more ‘culturally authentic’ version.". But the huge boulders Harker climbs through at the foot of the waterfall look like Inchbold could have painted them. And then there’s Isabelle Adjani as Lucy Harker, dressing as William Morris’ La Belle Iseult to conduct her rituals, or lying in her flower-strewn bed awaiting the vampire looking just like Millais’ Ophelia. To associate it so strongly with a pre-Raphaelite aesthetic – gloomy, eroticised, timeless, beautiful – is apt, and it reminds us Herzog’s doing what they (and Stoker) did, making reinterpretations of interpretations and romantic retellings of much older stories. Herzog’s references bring these other stories to mind – both Iseult and Ophelia are grief-stricken and lovesick, just like Lucy – but they also deepen the visual richness of his film. Its soundtrack, with music from Wagner’s Das Rheingold – another story of a monstrous tyrant drawn from myth – is another intertextual layer.

Herzog’s film is beautiful, and Murnau’s Nosferatu looks lovely now too; Eureka’s release is of a luminous new restoration. The film was famously made without the permission of the Stoker estate, which later sued and won the right to destroy all the prints, despite the changing of the characters’ names and relocating the story from Whitby to the fictitious town of Wisborg. Nosferatu has gradually been rediscovered and rebuilt over the years, like a papyrus being reassembled, and if you’ve only seen the monochrome public domain version, the restoration is essential viewing. The scenes have been tinted, as they were originally, to signify daylight, twilight or candlelight, and they look gorgeous. Also, the intertitles have been restored and missing ones beautifully reconstructed. They’re wonderful; by showing us pages from books and letters as well as cards for dialogue, they reflect Stoker’s epistolary novel and give the storytelling depth and layers – the whole thing is framed as one of those ghost stories told by someone reporting events third-hand.

Perhaps that’s the key to the relationship between the two films. Murnau’s film is a classic Gothic tale, reported by an impersonal narration far removed from the story. Herzog’s film feels like a response, like a characteristically personal account of what resonances such a tale might have for the one hearing it. As such, it does nothing to undermine the authority of the original, and perhaps this is what Herzog means when he says he tried to connect his film with his "German cultural heritage," to explicitly remain in the inferior position of response, reminding the audience of the original’s greatness, rather than attempting to replace it. It’s a humble intention if so, and Herzog’s film thankfully can’t help but go beyond it. Its impact doesn’t rest entirely on how fast it sends you back to Murnau or any other vampire film.

There are over 200 filmed versions of Dracula already, to say nothing of the novels, stage and radio plays and comics. Filmmakers have continued and will continue to adapt Bram Stoker’s vampire tale; it seems to provide ridiculously fertile ground, as Herzog says. Herzog’s film was one of three Dracula films to be released in 1979, but the Count dropped out of fashion for a while after that. The ‘80s and ‘90s saw relatively few adaptations other than Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1992. Post Buffy and Twilight, though, the scope for reimaginings expanded considerably. The newest one, an NBC TV series starring Jonathan Rhys Meyers, is about to air at Halloween, just as the Gothic season starts. However many remakes there are, it will always be worth revisiting Murnau’s original vision, and Herzog’s lyrical reaction to it, and with these lovely new prints going on general release, there’s never been a better time to do so.

For more information on the BFI’s Gothic season visit https://whatson.bfi.org.uk/Online/default.asp