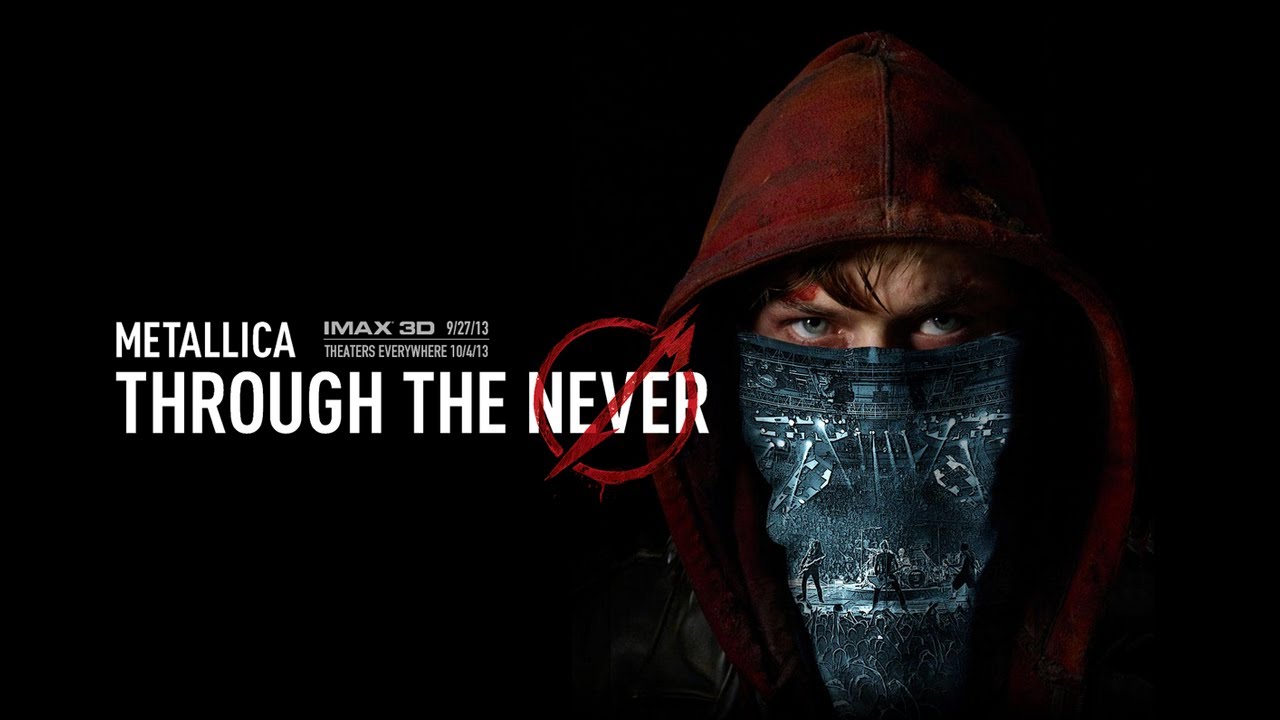

Ahead of this weekend’s release, Lars Ulrich was in town promoting Through The Never – Metallica’s new concert movie with a narrative twist. Directed by Nimród Antal (Predators), and starring Dane DeHaan (The Place Beyond The Pines, Chronicle) alongside Metallica, the film is an intriguing blend of narrative and live concert, and is rather difficult to place.

As well as discussing the film, Ulrich also said that the band were due to make an announcement on Tuesday October 8, dropping the tantalising clue that the statement would bear some relation to Iron Maiden’s 2010 album The Final Frontier. Does this suggest that Metallica are set to release their longest album to date? The Final Frontier is Maiden’s lengthiest studio album, clocking in at a whopping 76 minutes long. We already know that the band are recording a new record in 2014 with a view to releasing it in 2015, but does this mean it will be longer than Load, which is already a whopping 79 minutes long, or if we’re being liberal with what constitutes a Metallica album, longer than Lulu, which is an unseemly 87 minutes long? Or does the hint suggest that Metallica’s as yet unnamed 11th album will have a science fiction theme? Or possibly these two factors combined, making it a cross between Sandinista! and Event Horizon? (Interestingly enough The Final Frontier was preceded by a free to download track, ‘El Dorado’.)

Thirteen years on from Napstergate, ten years on from Some Kind Of Monster’s candid portrait of the quartet and five years after The Quietus’ own run in with the band, Ulrich remains the most infamous member of Metallica and the undoubted public voice of the band. In Some Kind Of Monster, he came across as outrageous, starry-eyed and an, at times very moody and spoilt teen in the body of a forty-something drummer (see the incident below).

Tucked away in some corner on the fourth floor of a central London hotel, I meet Lars at a roundtable with several other publications to talk about the new movie. The first discernible signs of age and maturation are as apparent on his face as in his demeanour. He’s friendly, chatty and open – a changed man from the arrogant superstar from the St. Anger days. It’s plain to see, Lars Ulrich is fully aware just how uncertain Metallica’s future is, and of how insecure a legacy can be.

Obviously this film’s a big financial risk – is it worth the risk?

Lars Ulrich: That remains to be seen! Ask me when I come back and talk about the new record two years from now. I’ve no idea. I do know that we rarely consider other options, so compromise is not Metallica’s major strength. And I think that the fans hopefully appreciate that if its got the word ‘Metallica’ written somewhere on or near it, that it comes from us; creative experiences aren’t really ones we share with anyone other than the closest few that we sort of purposefully let in. So, to sit there and take a bunch of money from a bunch of people to then have them [be] involved in editing and controlling the movie and so on just seemed wrong. That of course was before the project ran amok, but they always run amok so it’s nothing new. I hear myself say the same shit every couple of years in various ways. We’ll have to see. In Metallica we don’t look at things as… there’s a word called ‘cross-collaterizing’. You sort of put everything against everything else so it’s not [a case of], “How is the movie going to do, as itself?” It’s not like an isolated entity… I think nowadays in media it’s very much, “What did it cost? What did they get back? Was it a success? Was it a failure?” It’s slightly more complicated than that, and that kind of breaking it down to absolutes really doesn’t interest me. This is another chapter in Metallica’s existence, and I’m sure that if we don’t make all the money back, then, I dunno, [we will in] T-Shirt sales seven years down the line. Something good will come in the wake of these projects. It’s just sort of how we roll.

Where did the idea – to have a narrative accompany the stage show – where did that originate? Did it originate with one particular person?

LU: Er, nah. I think it originated within the band when we felt that if we were going to do a movie of this scale that there should be something in there other than just us, and so as we sat and talked around what that could be we quickly felt that having a story in there would be really interesting because it just felt unique and weird and challenging. I guess to a degree we felt that the reason Some Kind Of Monster ended up resonating with so many people was that there was a story in there, and it was not just four guys making a record. I think that with a movie of this magnitude, you need something. I mean, pick a movie [such as] Iron Man. It’s not two hours of him in the suit flying through space, it’s got something to balance out the action sequences. So if you equate the live [footage] to the action sequences, there’s got to be something else there to balance it out, or else it just becomes a fucking blur. In a lot of these films, people cut away. In The Wall [they] cut away to animation, or in The Song Remains The Same they cut away to musicians in cars or riding on horses or whatever. In some of these other concert films they cut away to people getting out of airplanes or getting massaged, or whatever it is they cut away to. They always cut away to something. So we figured, we’d cut away to something, but not necessarily James Hetfield eating a sandwich. [Journalists all laugh] Well maybe in the DVD extras… But we wanted to cut away to something that we felt would be more interesting, and that was the story that Nimrod came up with.

Do you think there’s more potential in the narrative/concert film crossover? What I have in mind is a sort of heavy metal Fantasia, where the narrative is all driven by songs.

LU: You’re getting in to very blurred territory. What’s Purple Rain? What’s Rude Boy? Where does The Wall fit in to this conversation? You’re talking about an area of film-making that’s still fairly undefined, and so, there are people who are, I dunno, brave enough or stupid enough (depending on how you look at it) to jump in there. We always jump and try to figure it out as we’re falling. We always sit there and go, “Maybe we should have thought this through a little bit?” People talk about Michael Jackson’s Thriller, and how videos become short films, and then there’s all this type of stuff, so obviously it’s a pretty rich area for mining of potential creative endeavours. So we’ll see how it plays out.

Have you ever had a show get as disrupted as the one in the film, and if so what happened?

LU: Well all the stage antics in the film are obviously, for astute observers, a sort of a nod to the Metallica concert past. So the stage collapsing and all that stuff is obviously a nod to the 96-97 Reload Tour where it sort of collapsed at the best of our ability. Now with new technology and all this type of stuff everything’s bigger and more ridiculous and sillier than it was twenty years ago, but that’s kind of fun also. When we did that go-around, that was fifteen years ago, that was before internet and before information travelling the way it does now, so every night when people fell out of the lighting rig and stuff like that, people would call the radio station and go “there’s been an accident at the Metallica show!” – but people didn’t know that it had happened in Phoenix the night before, because news didn’t travel the way it does now. It was a pretty big deal back then. We’ve certainly obviously had our fair share of Spinal Tap-esque endeavours – way too much for a roundtable – but we’ve lived most of the silly ridiculous things at some point or another, as you have in a 32-year old career.

What was it like seeing yourself in on the big screen and in 3D?

LU: After Some Kind Of Monster, nothing scares me. After Some Kind Of Monster it’s all good, it’s easy. So silly Danish accents, and double chins and receding hairlines and all the rest of it – I’m pretty thick skinned. I sat with an audience in LA at the Universal City where I had to introduce the film a week ago and watched the first two thirds of it, on a big IMAX screen. All filmmakers will sit there and say, "You have to see my movie on a big screen because that’s the way it was meant to be." But this movie really deserves to be seen on a big screen, because of the sound and the whole thing. I’m sure it’s going to play fine on this thing [grabs my smart phone] six months from now, but that big fuck off screen – it’s cool.

Going back to the stage theatrics in the film, you had a Ride The Lightning electric chair and the Lady Justice statue. Will you ever be putting those back on to the tours that you do regularly?

LU: Well we’ve been kind of getting away from all the theatrical stuff, and what we’ve been doing for the last fifteen years has been mostly about reconfiguration. I don’t know how much of that shtick is so much on our radar these days, but I think as you get thirty years in to your career [you do look back]. When Rick Rubin sat down with us five or six years ago, he said, "It’s okay to be inspired by your past, and it’s okay to acknowledge your past, and it’s okay to give a nod to your past.” Metallica had spent a lot of time – not necessarily running away from our past but reinventing ourselves and this concealed a fear of repetition, a fear of being stale and stagnant or whatever. And so, increasingly, we’re okay with these elements of our past, but we don’t want to dwell on them, and we certainly don’t want to become a sort of ‘classic band’ in that way. We’d like to continue to move forward to the best of our ability and look forward. I do think that there’s a chance we may tour at this stage, so all those shenanigans may be on tour at some point. We’re not booking this tour as we’re speaking, it may be five years or something – right now we want to get back to making another record, and doing that again – but we probably will tour this at this stage we say. The odds of it go up everyday as I hear people ask about it.

How’d you go about choosing what songs you’re going to put in to the film? You’ve obviously got a huge catalogue of music.

LU: On an undertaking of this size, there are certain songs that lend themselves to big fuck off cinema-making more than others. This is not the appropriate occasion to start bringing out all those obscure songs we have never played live before. I do think that obviously there are certain songs that lend themselves [to this], so I tried to do the best I could with our… I don’t like to use the word "hits"… but our more well known songs. To try and find the best balance, and also not being previous about it, because, well in the post-production for this movie over the last year a lot of things were moved around. So stuff is out of sequence, and some songs are no longer in their entirety. There have been some snippets; some things have been snipped. The battle cry was always, "What’s best for the movie?" and to find a way to make the best movie possible and not [a faithful film] about the "Western Canadian concert experience" or whatever.

‘Orion’ at the end was perfect. Was that always the plan, to have that at the end in that style?

LU: Nothing was ever "the plan". That was like a last minute thing. Mark Reiter – one of the fine people at [Metallica’s managment] Q Prime – said, “How about playing ‘Orion’ during the end credits?” So I replied, "You know what Mark – that sounds like a fine idea." So we went up [on stage and played] through ‘Orion’ about four times in an empty arena, and there you go, it’s in the movie. And you like it, so it worked.

What was the inspiration for the more horrific aspects that Trip had to encounter during the film?

LU: If Nimrod Antal was sitting in this chair with you during this fine roundtable, he would answer it this way – because I have heard him say this when I’ve sat next to him. He would say that there’s a book called The Alchemist, which inspired him, which is about the human journey rather than the destination. The other thing that he would tell you, because this is really his story, is that when we all sat down and talked about what this could be and so on, that we said, “Go away young man and come back to us with a story” during the occupy movement of a couple of years ago. So he was quite inspired by the energy in that and correlating some of that energy to Metallica and, he has a word for Metallica music called, “fuck you music”, so there was an element of some of that energy that was going on politically in the world. And then The Alchemist – that was where those inspirations were drawn from.

You recently told a radio station in California that there’s going to be ‘another frontier’ heading in Metallica’s direction this December. Have we got any indication what that might be? A Metallica Christmas album? Metallica the Musical? Lulu Part 2?

LU: Lulu Part 2 – just to piss everybody off! [laughs]

I believe that there’s an announcement on October 8. But don’t hold me to that, I’ve been a little caught up in [the film]. It’s not anything of that magnitude.

No Christmas album?

LU: I wish! There may be a few of you that would be disappointed, it’s not anything quite at that level. I found myself telling one of your colleagues earlier, there’s an Iron Maiden album called The Final Frontier. So I’ll borrow that from my interview an hour ago, and say, “My clue will be the Iron Maiden album, The Final Frontier.” There you go.

How did you come to work with Nimrod?

LU: He was mad enough to want to do it. He knows that I spoke to other people before him, and none of them were mad enough, and none of them were up for it enough, and everybody had questions and reservations. A lot of people had raised eyebrows and frowns on their faces, and Nimrod was just fucking up for it. Enthusiasm trumps everything. Metallica played a pretty significant role in his life when he was growing up in Hungary, and it’s always good to have a little bit of Eastern European attitudes and aggression in there. You can never go wrong with that.