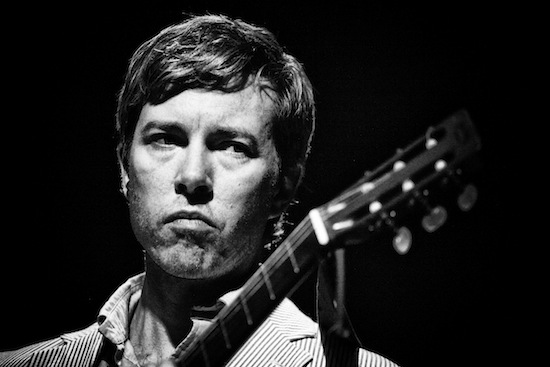

Photograph courtesy of Iñigo Amescua

Bill Callahan’s latest album, Dream River, is as luscious as the title implies – full of warm analogue tones, flutes and fiddles, and softly-tapped hand drums. But it’s not all smooth sailing: like dreams themselves, Dream River has deep undercurrents, some of them quite disturbing. In many ways it is a continuation of his 2011 album Apocalypse, whose second side focused on a mellow American folk sound indebted to Willie Nelson’s Stardust and Fred Neil. In Dream River, however, there’s a faint whiff of decay in the sumptuousness – something that presages both the inevitability of death and its necessity for rebirth (a dynamic captured beautifully on ‘Spring’).

In many ways Dream River represents a deepening of focus for Callahan, whose first two albums under his own name (2007’s Woke On A Whaleheart and 2009’s Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle) sounded giddy with the possibilities presented by casting off his old stage name, Smog. While many of Smog’s albums focused on experiences of alienation with a kind of candour that could make a listener feel rather uncomfortably like a voyeur, Callahan’s post–name change albums are more outwardly engaged – they engage in a dialogue with the listener. Dream River may eschew the musical restlessness that drove the bright, optimistic sound of Woke On A Whaleheart and Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle, but this doesn’t represent a "slowing down" or a closing in – rather, Callahan is digging deeper.

One of the most surprising things about Dream River was the announcement that dub versions of two of its songs would be released. What drew you towards dub music? Why did you tackle the project of creating dub versions of these songs?

Bill Callahan: First can I say that the last time I talked to the Quietus was at a pub in London at the bitter end of that day’s press. I had flown in from the U.S. that morning, not having slept on the plane and had a couple hours at the hotel before I had to go do a radio session. I couldn’t sleep – I knew I was fucked! I took a shower to get rid of the radiation. Then I was strolling around my tiny room naked as a jaybird when the maid walked in. Jealous much? I did promo stuff all day and finally was led to a pub where I thought I could get a god damned beer, first of the day, while talking to Quietus lady. But she was given short time and so wanted to plunge into it – no time to waste going to the bar to order sweet sweet drinks! I was asleep on my feet. Lagged and shagged out as you say. Building a sentence was like building a wall against the waves.

Dub is a spiritual, abstract, visceral, mystical thing. Finite and infinite at the same time. Deeply rooted in the earth and in outer space. It was invented in Jamaica and no one else really messes with it as it is greatly abetted when the original song has a reggae rhythm, which my songs largely do not.

My reason for doing it is simply for the fact that I love dub music (from 70s Jamaica only)! It’s a genre that has come and gone. I don’t think the digital age will usher in a new appreciation for it. It’s a pensive [music] and [it is] body music. Neither of which I think are characteristics of this digital age.

Speaking of "this digital age", Dream River sounds a lot more analogue and perhaps more deliberately imperfect than Apocalypse; there seems to be a fair bit of tape hiss and other artefacts of analogue recording throughout. Is this something of a protest against the Teflon-smooth, glossy production that even amateur recording artists can now achieve thanks to the ubiquity of products like Pro Tools?

BC: It’s not a protest. It’s just what sounds least distressing to my ears. Digital is distressing to me. There isn’t deliberate tape hiss. There is, at the beginning of ‘Winter Road’, some guitar pedal hiss fed through a Morley and a Leslie to get a sound like tyres hissing on fresh snow. And we threw some bolts and coins into the mix just to make it chewy. Apocalypse was a sparser record, less overdubbing.

Aside from an interest in dub, I also understand you have an interest in contemporary hip hop and R&B — you played Snoop Dogg’s ‘Drop It Like It’s Hot’ and R Kelly’s ‘Ignition (Remix)’ when you guest-programmed ABC-TV’s Rage back in 2009. What influence does dub music and hip-hop have on your own music? Do you try to honour or draw inspiration from this music in your own?

BC: Getting people interested in words is a wonderful thing. That’s what I think hip hop does, in part.

How do you feel now about the way you incorporated elements of Sir Mix-a-Lot’s ‘Baby Got Back’ in Smog’s ‘Real Live Dress’ back in 2000? Is this kind of ironic appropriation something you dropped with the Smog moniker?

BC: You’re way wrong. I love ‘Baby Got Back’ and think those lines are pure and true. Keeping it simple. It wasn’t irony, it was admiration for the clarity. It was acknowledging that I couldn’t top it. If I quote something it’s because I can’t top it. No irony.

Dream River sounds to me very much like a continuation of the second side of Apocalypse, where all of the nervy energy of the first half of that album gets resolved and replaced by an overwhelming sense of ease and repose, although it seems that there are some troubling undercurrents in Dream River. What is it that currently attracts you to these musical tropes that imply ease and contentment?

BC: You get interested in modes of thought, views, topics. These topics may interest you particularly at a point when you have some tie to them, but it has to go beyond that unless you want to make a crummy LP. There is ease in death. I was reading – still am reading – the Tibetan Book Of The Dead as I worked on this record. I estimated how many years I have left on this planet and divided the number of words in the book by how many days I may have left. To work out how many words I could read per day if I wanted to make the book last until my death or nearby.

Woke On A Whaleheart seems to have a kind of manic, almost brittle optimism about it, and you spoke in interviews at the time of its release about feeling as though you had got rid of a shroud by casting off the Smog moniker, and of feeling giddy at the ease at which you could do so. Over six years have passed since you started working under your own name, and Dream River certainly doesn’t sound as giddy as Woke On A Whaleheart – how do you now feel about the Smog moniker? Have you come to a rapprochement with that aspect of your creative self?

BC: We sped the tape up a little bit, 70s style, to get that cohesive airless optimistic sound. Per order of the producer or co-producer Neil Hagerty. “Smog” is now a good personal zinger in my life. I can say, “Looks like a Smog fan!” and it gets the laugh. It was a different person, different people. It’s there forever for anyone who needs or wants it but for me – I’ve had to take it off the scales, it’s not something I invite to weigh in on the rest of my life.

You say you’ve had to take Smog off the scales, yet traces of that figure remain, particularly in your live set lists. How do you go about deciding what songs from that time are worth recuperating as part of Bill Callahan’s artistic identity? Is something like ‘Bathysphere’ on Rough Travel For A Rare Thing merely because it’s one of Smog’s better-known songs, or is there a deeper connection there?

BC: I meant I take those old recordings off the scales, not the songs themselves. The songs can live and change and be with me forever. ‘Bathysphere’ is like ‘Baby Got Back’ – it’s got a clarity that can’t be fucked with.

As your career progresses, you seem to be more concerned with America, both as a concept and as a concrete country, whereas much of your early work seems to be universal and placeless in its sense of urban alienation. There’s also a connection here with travel and motion – in Apocalypse’s song ‘America!’, your reveries about America are prompted by watching David Letterman while on tour in Australia; while Dream River is replete with images of motion: a plane flying home, a train passing by a hotel bar, a truck navigating a difficult passage on a winter road. What’s the connection for you between this sense of transit and this sense of space?

BC: If there is space you want to transit it. Else someone will come along and kill you. If you sit still you’re dead.

‘Javelin Unlanding’ is absolutely crammed to the gills as a song – the structure is quite complex, there are a lot of parts, and there are some quite sudden stylistic changes in there. It seems to be a rebuke to the idea that your songwriting is exceptionally sparse and simple. What draws you towards making music this dense and rich at this stage in your career?

BC: It’s really just a matter of giving a song only what it needs. That song happened to need a lot. The bare bones band version of it was fine enough but the transitions needed shaping, accenting. And then it needed a little spice, some rancid spice – because after the shaping, it was too perfect.

One of the most arresting moments of Dream River comes in ‘Ride My Arrow’ when you sing, “Some people find the taste of pilgrim guts to be too strong/ Me, I find I can’t get by without them too long.” Yet the same song seems to be explicitly pacifist: “War muddies the river/ And getting out we’re dirtier than getting in”. What’s the meaning of this contradiction between the sentiment expressed by the song and the violent imagery within it?

BC: There are different kinds of violence. Some of them are excellent. A ripping away from blind, unfeeling or greedy tentacles. That is radical.

Your current touring band is named ‘the Princess Peach Gang’ – what inspired the name? Are you a Super Mario Bros. franchise fan?

BC: My record label asked who I was taking on the road. I replied, “the Princess Peach Gang,” to let them rest assured that I would be backed by the finest. It has since been shortened to the Peach Gang, for the Summer at least. I’m not a Mario Bros. fan. The only game I care about is Zombie Highway.