Over three decades into an incredible career at the forefront of electronic music, Gary Numan is still passionate, motivated and utterly resistant to the music industry’s shiny happy bollocks. Right from his genre defining Tubeway Army albums and first solo LP The Pleasure Principle to October’s upcoming LP Splinter (Songs From A Broken Mind), Numan has proved himself to be a true innovator and survivor, moving through punk, synth-pop and industrial, creating a legacy of crossover music that’s influenced everyone from Nine Inch Nails to Underground Resistance and even Kanye West.

Splinter… is a characteristically dark record – all heavy machine beats and driving electronic lines. Tracks like ‘Here In The Black’ and the surprisingly beautiful ‘Lost’ (which will doubtless become one of Numan’s greatest offerings…) clearly encapsulate the personal darkness that Numan felt when penning the tracks; the record is as defiant as it is tragic, from the classic electro-rock of ‘I Am Dust’ it feels like being dragged down to the aural depths only to emerge that little bit stronger by the time the foreboding tones of ‘My Last Day’ close things off.

Just shy of the album’s release, over a clear line to America, he speaks to the Quietus about the issues and challenging experiences over the last few years that have influenced the creation of this new record, as well as the highs and lows of a move Stateside. We find out what it’s like now, living in the sun for a change, and hanging out with all the cool kids instead of just sitting indoors and watching the rain fall. Yeah, the Nume doesn’t miss our charming British weather one bloody bit.

Could you talk about some of the challenges that came with moving over to the States?

Gary Numan: I have a family. So, if I went to America without a Green card, when my children became 18 they would have to reapply in their own right, and they could face deportation. I couldn’t risk that, so I had to come here with a Green card for a family, meaning that we can be here for ever. I’m not sponsored by anyone, I’m self-employed, and so I had to prove that I was an alien of extraordinary ability. I had to prove that I have been exceptional in some way, above and beyond other famous people and that’s why it was tricky! It took me two years to build up a decent portfolio. The fact that I have been considered influential and innovative is useful. I had to go through all of my press cuttings and TV shows to find significant people saying something very complimentary; I needed to show how much chart success I had, and how many genres of music I have had influence in, and the more influence, the better it is. I needed testimonials from people like Trent Reznor, who gave me his, right after he won his Oscar. I got letters from a Los Angeles Times journalist, from the president of a record company, from a couple of mega producers, Alan Wilder of Depeche Mode did one, as did Dave Navarro from Jane’s Addiction. I had to do it very carefully and go through a lawyer the whole way. If you’re just a kid in a band, I certainly wouldn’t bother with it. I lived here before back in the early 1980s, I just got a work permit and came over. It is a great place to be. I’m not saying people need to come here; that’s an individual choice. There’s a huge amount of music. I do notice that the way people interact here is better. People just hang out and play together. Dave [Navarro] got in touch with me a little while ago, because he and some of his mates were doing something at a few clubs. I couldn’t do it unfortunately, but they were doing cover versions of other people’s songs and they wanted to do ‘Cars’ with me. There’s a much more, ‘We’re all in this together’ type of vibe, and it’s not as aggressively competitive as it seems to be in England. I find it a very healthy environment to be in.

It must be great to be able to just pop out to shows with the family and see all these great bands?

GN: It’s fantastic! A little bit ago we were in Chicago at Lollapalooza. We just met so many people – it’s all really cool and friendly. I wasn’t just hanging out with bands, but all kinds of people. I was hanging out with a lady called Bonnie [Bonita Pietila] who has won three Emmys because of her work on The Simpsons; just these really talented people. Then, we were in San Francisco for Outside Lands Festival. We’re just being exposed to so much more music here. Going to a festival in the US isn’t quite the same as going to a festival in the UK. The last festival we did there, I was up to my fucking knees in mud. I couldn’t move! It was horrible. I think in Britain we just accept it. We’re brilliant at just getting on with it. When I do a festival in Britain, and I’m looking out at however many thousand people and they’re just covered in mud, I just think, "How brilliant are you!?" I really do think that British festival goers are the best in the world. They’re always there, loving it and laughing in dreadful conditions. Americans don’t know how easy they have it!

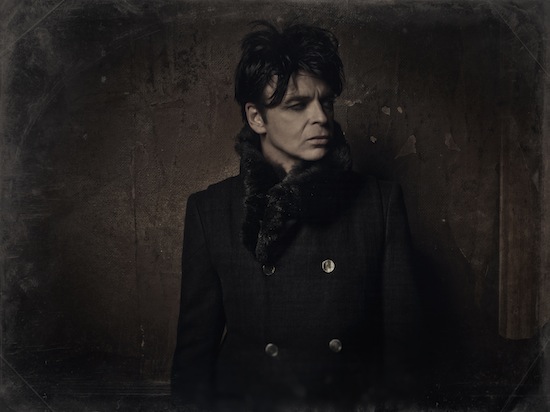

Is the cover for Splinter… a more direct reference to the ghost that often features in your artwork?

GN: It’s not a reference to the ghost that I saw in Piccadilly Station, no. But that ghost has played a big part in my early career. It was on the cover of Replicas and the cover for The Pleasure Principle. I did an album called I, Assassin where I am dressed like the ghost. For Splinter I wanted it to be vaguely ghost-like, I wanted it to be a photo of someone from way back when, who is broken, effectively. A lot of the songs on this record were done when I had depression which I had for about three years. I was on medication for it. This happened before I left England, actually. My wife also suffered from the same thing after our second baby; she got postnatal depression and that carried through to our third baby. She had it for a very long time, and mine was a reaction to what she was going through. It had an effect on our relationship; we had three children very quickly and I really struggled with that. Adapting from having a relatively free and easy life as a couple to suddenly being a parent of three young children, I didn’t take to it well and felt guilty, because of course, I love the kids. I also turned 50 when all this was happening, so I had a proper mid-life crisis and started to panic about getting old; I’d get panic attacks and start crying in the middle of the street. Me and my wife Gemma were not getting along, it’d been amazing, and then the children came and we were stressed and didn’t sleep, so we were getting at each other. A lot of the album comes from that period, even the songs that I’ve written more recently go back to that period for inspiration. I honestly felt broken; my mind was, my relationship was. As food for creativity it was brilliant, but to live through? It was horrible. We did come through and out of it, and some of the songs from the album were very important in helping me to do that. You know when you’re in a bad period with someone, and you forget the good stuff, and you’re always ricocheting from one argument to another? I was in that. And I came close to walking away, and I think Gemma would say the same. I went into the studio in one of those rare songwriting days I had during the first years of my depression and I wrote a song called ‘Lost’ which is on this album. I started to write down what my life would be like without her, and it changed everything. It was a really good experience, because it made me remember everything that’s amazing about her. I wrote this song and was pleased with it, but I got really upset. I went inside and I gave her a big hug and apologised, and everything started again. We started to understand and sympathise with each other, because we were having the same struggles. Largely, the reason I write songs has been for therapy. I talk a lot on the phone, but generally in my private life I am not a big sharer of problems, I sit and stew on things. In a song, I have to think about things more deeply, and from all kinds of angles to make sure that it accurately reflects what I feel and what I’ve been thinking. That’s very therapeutic. I certainly did that with ‘Lost’, and I wouldn’t say that song saved our marriage, but it helped.

Talking about another track on the album, can you set the scene for ‘Here In The Black’ and the inspirations behind that “desolate shadow of fear” lyric?

GN: That one was about a change of circumstances. I was feeling really lost, lonely and frightened. I didn’t feel like I had anywhere to turn. My life felt as if it wasn’t my own anymore and it had been taken over by these three wonderful children. Nevertheless, it wasn’t my own life, I wasn’t making my own decisions. I was close to running away. The song is the story of someone being somewhere dark and frightening; there’s something coming for them. They’re trying to get away, but they can’t and it feels deadly. I wanted to create a story that would give the listener a sense of desperation and helplessness. Normally my songs are a bit more personal, but I do really like what I did with that one. I think that’s probably the best lyric on the album.

Can you also talk us through ‘My Last Day’ which is the last track on the album, it’s a very haunting effort?

GN: That song is about a friend who we’ve got to know since we have been here, who had a real life threatening situation concerning her brain. Actually, she recently had an operation and I think they’ve saved her. Everyone thought she was a goner, and a week before the operation she was going out and effectively saying "goodbye" to everyone. It was a highly risky procedure and the chances of surviving were less than 50/50. It was so tragic, because her and the family are so lovely. Anyway, that’s happened and she’s all good. So I am relieved about that. But when I met her, I was just struck by her bravery. The fact was that she could’ve died at any moment of any day, and all I could think was, "How the fuck could I live with that?" To be honest, that would finish me off. So, I started to write a song about what it would be like if I was told I only had one day left, and what things would go through my mind. That’s the lyrical part of the song; for me, it was about the fact that I would miss my children and all the things that I could’ve shared with them. When I got to the end bit – you know that when you die, they say that you’re supposed to see this glorious light? I wanted this slow and quite sombre song to explode into this huge anthemic thing. The more I worked on it, and the more strings I was layering and counter-melodies I built into it, I started to see it as this very filmic piece. The second half of the song was me trying to create this epic filmic sound. I really love it, but it does sound like two very different things stuck together. It’s very much me having a stab at doing something that I would feel appropriate for a film.

How do you anticipate keeping up this bleak, dark and heavy sound now that you are in one of the most beautiful, if slightly artificial places in the world, referring of course, to California?

GN: Half the songs on the new album were actually written when I came here. But I can remember what it was like before. I choose not to write about the mountains, the blue sky and the palm trees. I don’t find that very interesting from a songwriter’s point of view. It’s a lovely thing to live in. I genuinely think that the creative part of my brain is tucked away in a little dark corner, and the only things that reach it are dark things. I will spend all day outside looking at the mountains or swimming in the pool, and then I will meet that lovely lady that had the brain problem, and that’s what I will write about. It doesn’t seem to matter where I am. I have certainly written hundreds of songs where I have been very happy. When I wrote Jagged my life was brilliant. That album was all about people that I’d met in the past; the ones that were a bit weird or horrible, and things that I’d done that I was ashamed of. I choose to go to these places as a source of inspiration for what I write. Look at ‘Cars’ which is probably the most ‘pop’ song that I’ve written! That’s about people trying to beat me up in London, and ‘Are "Friends" Electric?’ is about a robot prostitute! None of it’s been happy, even when I was number one in the charts! There have not been happy reasons for writing a song! I am a reasonably happy person. I am doing what I want with my life.

Since you’re an avid flyer, will you be surfing or skateboarding now that you’re in the States?

GN: I am terrified of sharks, so I don’t even know if I’ll ever swim in the sea here, let alone go surfing! My kids want to do it! Eric Avery from Jane’s Addiction is a surfer and he’s teaching them. Also, Robin Fink [NIN]’s wife Bianca is an ex-Cirque du Soleil performer, and so all three of the kids are learning aerial ballet with Bianca! They’re getting to do some really cool things that they wouldn’t have got to do back home. For them, it’s great! I really want to get into skiing and snowboarding. I think we’re going to do that later this year. In Los Angeles, you’re only ever half an hour away from places like Big Bear Lake where even in the Spring, it’s still snowing. You can go skiing in the morning, and if you want go surfing in the afternoon! How cool is that?

You’ve got some tour dates coming up, as you get older how do you warm up for shows?

GN: I seem to be really lucky and ageing well! My wife hates me for it. I don’t exercise, I don’t even warm up my voice. I get on the bus, turn up at the gig, thrash myself about for a few hours and then have a party on the bus all night. I’ve got an iron core constitution. I get hammered as well. I don’t get hangovers. I wonder how long it’s going to go on for? I’m 55 now though, and I am exactly the same as I was when I was 21. I don’t exercise, I eat rubbish and party all night when touring. I love it. I don’t have any problems at all. I am dreading the day when I start thinking, "Oh, I have to get in shape!"

Where were you when you found out that NIN wanted you to open for them on their tour at the end of this month?

GN: Trent [Reznor] had a birthday dinner with a few people and we were invited to that. Gemma was talking to him then, and he mentioned something to Gemma like, "Oh, what’s Gary doing at the end of the year, is he busy?" She told him I was doing some gigs and then didn’t tell me that he’d asked, so she knew that something was brewing. Then, I got an e-mail one morning asking if I’d be up for doing the Florida shows. Oh god, man. It was just fantastic to be asked! I am a huge fan of the band, and I feel very close to them. Trent has been great since we moved here. We were only here a week and we’d been invited to one of his children’s birthdays, and there we met all his friends. He’s been lovely at making us feel welcome and introducing us to people. He’s such a cool man, and I am such an admirer of what he does, so for me to have had some kind of effect on that is something that I am hugely proud of. Through Trent I have also met Josh Homme from Queens Of The Stone Age and all kinds of other people who are just brilliant. I have been blown away by how cool and talented the people are here, and how easy they are to be around. There’s none of that American star nonsense. They are absolutely grounded, down to earth people that just love doing what they’re doing. They’re always supporting each other.

Splinter (Songs For A Broken Mind) is out 14 October via Mortal Records