Amid the slew of grunge acts snapped up in the early 90s, Cincinnati rockers The Afghan Whigs stood out for their soul influences – pitching at a mid-point between Hüsker Dü and Prince – and the murky areas of the male psyche probed by songwriter and lead singer Greg Dulli. They distinguished themselves in 1992 with their final release for Sub Pop, the Uptown, Avondale EP, featuring brooding readings of classic soul numbers. 1993’s Gentlemen was their first album for Elektra; the label struggled with how to market it and yet it has sold in excess of 160,000 – hardly up there with Nirvana but still the kind of figure that would have labels weeping in gratitude at the feet of any ‘cult’ group that could deliver it today.

To commemorate 20 years since that’s album’s release, I’ve opted to revive and revise a piece written back in 2004 that has never been properly published, although a version appears on the Rocksbackpages website. I do look at textural aspects of the music in places but it is unashamedly textual and Dulli-centric analysis – for more background and the full story of the album’s recording you should go directly to Bob Gendron’s contribution on the subject to the 33 1/3 series. As well as addressing some of the themes discussed below, Gendron also does a fantastic job of highlighting just what an odd-sounding rock band Afghan Whigs were at this point, and why that was. As he points out, the songs on Gentlemen "are strangely arranged, often tuck-pointed with irregular tempos, bizarre fills, difficult solos and jazzy harmonics." Insights range from Rick McCollum’s Fender Jazzmaster being crucial to the band’s sound to Dulli’s searing but tunefully approximative vocal takes on several songs being down to them being recorded while he was drunk and cocaine-cocky, trying to impress a stripper he’d brought back to the studio. You also get a more autobiographical take on the album’s ‘story’ – the collapse of Dulli’s relationship with his first real love, Kris. That’s the warmer version, looking at Gentlemen as the snapshot of a mindset at a moment in time rather than an alarming ‘state of gentlemankind’ address.

But ‘Dulli’ here for me is the persona, not the person, however much back and forth there may have been between the two. It’s one not too far removed from Mad Men‘s Don Draper, the ultimate TV seducer/devil/lost soul who may or may not be beyond redemption. But whereas Mad Men places Draper in a wider socio-historical context, positing him as the product of various forces rather than just of evolution (obviously it’s a long-running TV series with the luxury of time to fully explore the themes), Gentlemen is claustrophobically, monomaniacally focused on a (heterosexual) relationship, almost exclusively from this guy’s perspective. There would appear to be no obvious explanations or justifications apart from what Dulli has referred to in interviews as the "lizard brain" (I’ve just swapped the lizard for a reptile!). There is, though, the potential for something like a post-structuralist feminist take, which is to say that the problem might not be down to some essential nature of men and women and more to do with socially constructed roles. And from that stems a glimmer of hope.

"On her way to work one morning/down the path alongside the lake/a tender-hearted woman/saw a poor half-frozen snake." ‘The Snake’ (Brown)

"Let me in, I’m cold." ‘Gentlemen’ (Dulli)

In Northern Soul classic ‘The Snake’, written by Oscar Brown Jr but popularised by Al Wilson (and based on Aesop’s fable of the scorpion and the frog) a woman chances upon the creature of the title nearly frozen to death. It pleads with her "Take me in, oh tender woman," which she does, gradually nursing it back to health. One day she returns home and the snake, now fully recovered, bites her. The woman is shocked, unable to understand this treachery. The reptile replies (with a grin): "Shut up, silly woman! You knew damn well I was a snake before you let me in."

One way of looking at The Afghan Whigs’s Gentlemen is as a loose retelling of this fable, with Greg Dulli in the starring role as the rascally beast, out in the cold following one relationship and ready for his next victim. (I managed to put the idea to Dulli once and he had never heard of the song but he seemed to appreciate the parallel.) In the song, the snake is a thinly-veiled representation of heartless manhood. In Dulli’s world, it’s the snake that is hiding just beneath the seducer’s charming gentlemanly exterior. The image of the beast within rears its head in the album’s overture ‘If I Were Going’: "It don’t bleed, and it don’t breathe/It’s locked its jaws and now it’s swallowing." The same lines recur in ‘Debonair’, which also adds "And once again the monster speaks/Reveals its face and searches for release."

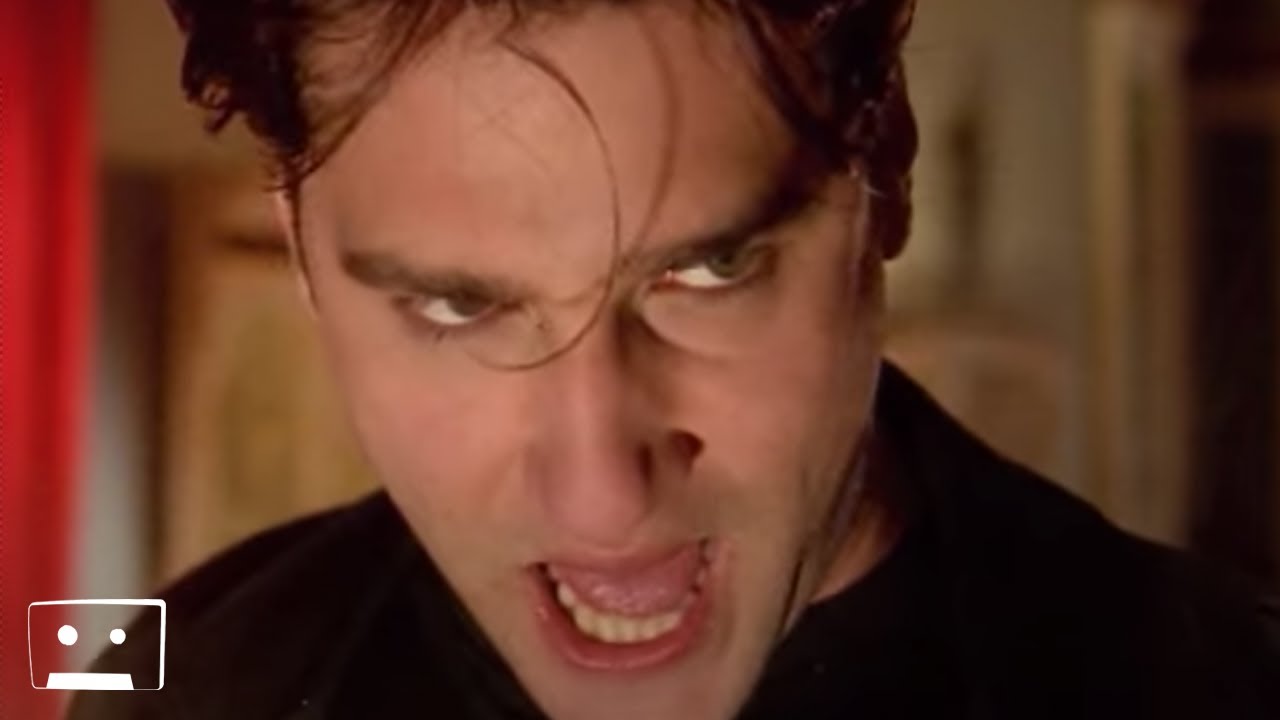

As politeness dictates, introductions are dealt with early on. "I’m a gentle man" is the refrain of the album’s title track, more like a threat than an assurance, and then on ‘Be Sweet’, Dulli lets rip with a full-on charm offensive (albeit one dripping with self-disgust) "Ladies let me tell you about myself/I got a dick for a brain, and my brain is going to sell my ass to you." But who’s buying? Some poor soul has, and she’s clearly not the first. All of this is terrifically character-acted, and as the album progresses Dulli brings the same intensity to bear on a range of relationship struggles. On ‘What Jail Is Like’ he’s claustrophobic, a trapped animal, while on ‘Fountain And Fairfax’ he’s a drunk who’s cleaned up his act for the woman in his life but finds he only resents her and hates himself even more. Here he delivers a particularly unsettling vocal performance, virtually gargling and foaming at the mouth.

Dulli’s character is also abusive, certainly in the emotional sense. Actual physical harm is never mentioned but songs like ‘Gentleman’ and ‘Fountain and Fairfax’ feel violent. There is a risk here – that the physical pleasure given by the music (the barrelling riff that opens ‘Gentlemen’ is exhilarating) might be mixed up with the cruelty being meted out. In a way, this is apt, and poses uncomfortable questions. Can you deny having felt the pleasure of succumbing to cruelty or anger? Have you ever enjoyed having power over someone? (The answer’s between you and your conscience…) But the violence, emotional or otherwise, is hardly glamorised. The music, funky but also dry and jagged, parched skin and broken bones, walks the line between beauty and descriptive, in-character ugliness. ‘Fountain And Fairfax’, despite its soaring mid-section, is founded on a riff that reeks of reptilian malice, while McCollum’s slide tones seem to literally heave and wretch. Any empathy should adequately be set off against real disgust.

Which brings us to the question that pleasant, beta males in particular can’t help posing – why do women go for that alpha male bastard? Are they asking for it? (Quite sensibly, people have been asking more recently whether the beta males necessarily have the moral high ground). The album avoids offering any neat answers, but it does succeed in uncovering areas that most pop writers prefer to leave unexplored.

The thorny heart of the issue is reached on ‘Since We Two Parted’ – a woozy, crawling ballad that describes an almost symbiotic relationship between the abuser and the abused. It also appears to lift a couple of references from an Angela Carter story, The Bloody Chamber. Carter’s "I clung to him as though only the one who had inflicted the pain could comfort me for suffering it" translates (in a more ‘rock’ vernacular) as "If I inflict the pain then baby only I can comfort you." The title of a Gaugin painting Out Of The Night We Come, Into The Night We Go mentioned in the story also features in the closing lines of the Whigs’ song.

In Carter’s story, a young girl becomes one in a long line to marry a cruel Marquis and live with him in his castle. Using a key that her husband has forbidden her to use, she opens up a room filled with torture devices, used by the Marquis to do grizzly things to his ex-wives (yep, now that does sound a little like Fifty Shades of Grey. I’d imagine. I haven’t read it. Really.) We are meant to understand that there is part of the Marquis that wants the girl to open the room and uncover the extent of his cruelty or perversion – as hellish as the revelation is, at least he doesn’t have to work to hide it anymore. Dulli puts in succintly in ‘Debonair’: "Tonight I go to hell/For what I’ve done to you/This ain’t about regret/It’s when I tell the truth."

Carter plays games with fairy-tale figures of beastly men and their female prey – she also ‘rewrote’ Beauty And The Beast – to investigate gender archetypes, and the degree to which we might all succumb to them. Perhaps, with this knowledge, we might at least try to change the rules. Dulli’s abuser in ‘When We Two Parted’ suggests that he, and perhaps his partner, are both playing out roles they’ve somehow been assigned: "You’re saying that the victim doesn’t want it to end/Good – I get to dress up and play the assassin again/It’s my favourite. It’s got personality." The role bequeaths him temporary strength but Dulli isn’t a cartoon cipher, he can’t just be the snake and not suffer for it. And what’s the strength for if the victim starts giving in too quietly, too easily – "If I could have only once heard you scream/To feel you were alive instead of watching you abandoning yourself." He’s disgusted with himself for what he’s doing, and he he hates her for letting him do it. If she doesn’t like the game, he wonders, why does she keep playing it?

Later, ‘My Curse’, a masterstroke, flips the point of view to give the female perspective. The victim gets a voice and it turns out she’s not just a poor, passive soul after all ("I do not fear you"). Scrawl singer Marcy Mays’ pained but dignified performance describes the push and pull between the partners, the shifts of power, the defiance and the hoping for something better: "I’ll try to break your back/You’ll try to make amends/Curse softly to me baby/And smother me with your love/Temptation comes not from hell/But from above." Not as cut and dried as the fellow would sometimes have you, or himself, believe.

It could be said that the message of ‘My Curse’ is received, but even if that’s so it’s apparently too late: "Since you’re aware of the consequences/I can pimp what’s left of this wreck on you." ‘Now You Know’ is where the relationship resolves and Gentlemen delivers a similar pay-off line to that in ‘The Snake.’ Again, though, Dulli, is a little less sure of himself than his reptilian counterpart. "Did you have blinders on my dear, or were you just willing?/Or was I unaware of the damage a lie can do?" In other words: Did you know what I would be like? Did I know? Would we have chosen differently if we had? More broadly – and I’m not sure this was Dulli’s intention but I think ‘When We Two Parted’ and ‘My Curse’ could at least point this way – one might also wonder which "lie" it is that does most damage. Is it the one about the courteous gentleman or the one about the beast inside?

Regardless, the snake’s tale ends here. And if that were all, most people could be forgiven for wanting to forgo such a bleak experience. Fortunately the album has more to offer – a further two tracks that give a little cause for optimism. Gentlemen approaches its close with an aching cover of Tyrone Davis’s ‘I Keep Coming Back’. Dulli finally breaks down and begs forgiveness – "I realise I treated you wrong/And I’m so sorry/Let me come back where I belong." Is there a way forward, or will the cycle just begin again? Either way it doesn’t seem as though, for the time being, we’re going to stop pairing off, forming couples, declaring love for each other only to find ourselves at times acting as though the opposite were true. But there’s room still for a concluding note, the instrumental ‘Brother Woodrow/Closing Prayer’. What begins with low, brooding cello and a menacing guitar figure reaches a plateau and then, with piano notes flickering like spots of light, begins a hopeful ascent. It feels like a prayer for a brighter future, for people to find better parts to play, and better ways of being together. And I think, ladies and gentlemen, that 20 years on we can all say "Amen" to that.