‘Grave To The Grind’ might have been the death cry of Carcass, as resonant as ‘Birth. School. Metallica. Death.’ if their career hadn’t been curtailed by the (unjustifiably) much-maligned Swansong album and the band breaking up shortly afterwards in 1995. ‘Tomorrow belongs to nobody’ they’d sneered, and so it came to pass.

You can call Surgical Steel a comeback album, but it amounts to nothing less than a vicious, glorious recapitulation of their musical cycle; you might call it an extreme music revolution. As influential as they were unpalatable, Carcass literally embodied ‘goregrind’: blood-spattered grindcore dispatched in churning blasts of medical horror. Their subsonic origins with Reek Of Putrefaction (1988) and Symphonies Of Sickness (1989) were served up out of miasmic lo-fi production and they fast became cult John Peel favourites. Their next two albums crystallized into an increasingly melodic death metal sound which reached its apogee with 1993’s Heartwork − their masterpiece − released almost to the month of Surgical Steel twenty years ago.

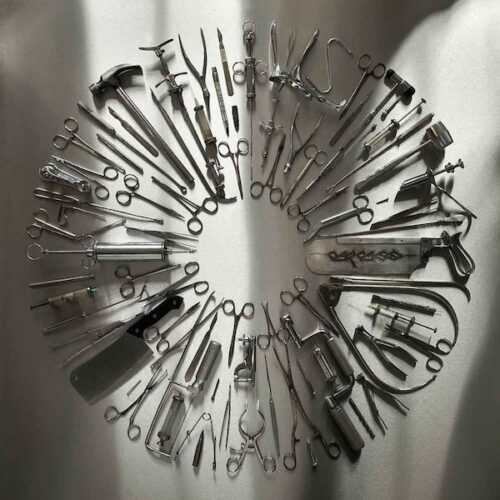

Surgical Steel opener ‘1985’ – though it references the year of the band’s formation − couldn’t be sonically further removed from that time. Its bombastic harmonies and cinematic sweep is actually strangely incongruous even with their later, more commercial work. But the album that follows is clinical and unremitting, virtuosic as much as it is vitriolic. It completes the circle, as its throwback cover imagery of their "tools of the trade" suggests.

Since Surgical Steel is being heralded as a corrective to Swansong’s deviation from their righteously extreme path and as the true successor to Heartwork, it feels right to look at the new album through the lens of Heartwork. Not only that, it is time to place Heartwork where it belongs in the pantheon of classic British rock albums and one of the only extreme metal albums that deserves such recognition.

What Carcass reached with Heartwork was a pinnacle of phenomenal production, unashamed musicality and track-by-track cohesiveness. It came at a historical moment after Metallica’s "Black" album and Nevermind when heavy music was reconsidered, reconstructed and found a new kind of populism. 1993 also saw the release of Chaos AD by Sepultura, an album which distilled thrash to its base elements and engaged with the politics of its day in a stripped-back, truly confrontational manner. Unlike now, even Slayer and many of the key influencers from the eighties were out of favour, and it fell to Pantera, Fear Factory and Machine Head to reinvent the steel.

Parts of the Carcass fanbase − split often by their preference for the different subgenre of whichever album they heard first/ liked best – have accused the band of selling their souls at the cross-roads of extremity and acceptability on Heartwork. But really Carcass managed to create a sound that, undoubtedly far from mainstream, opened up niche music like theirs to more listeners in a period when artists from the band’s home at Earache Records were being licensed to Columbia Records and (supposedly) a much wider audience.

Both Surgical Steel and Heartwork are produced by Colin Richardson. Overall though, the former has a drier, cleaner production whereas what is so arresting about Heartwork is the tone: thick and layered, it is both rich and monumental. It was captured at Parr Street studios in Liverpool and recorded in the same spaces as Coldplay’s A Rush of Blood To The Head (that band’s most Carcass-style album title). Inevitably the studio is also the site of a boutique hotel now – I’ve stayed there.

Richardson re-captured the searing dynamics of the demo the band recorded there in February that year, but polished it to a gleaming black shine. During the band’s gigs at the Camden Underworld earlier this Spring, Walker complained that Richardson had abandoned Surgical Steel to work on the new Trivium album, a pronouncement that would have embarrassed Trivium as much as Richardson, since every ‘extreme’ band these days would acknowledge Carcass as a treasured influence.

It is subject to much debate why the band became increasingly ‘musical’ over time and how responsible guitarist Michael Amott was for the shift when he joined after the first two albums. The grindcore, antimusic fanatics blame him for crimes after the fact, citing the considerable success of his main band afterwards, Arch Enemy, and its veering into bland Euro-metal triumphalism as proof that he steered Carcass down the track that would produce their third album Necroticism: Descanting The Insalubrious (1991) and subsequently the fully-blown melodic death metal of Heartwork. Amott wrote about a third of the material on the latter and contributed a substantial number of solos, but this feels like a group effort, and if anything the credit (note: not blame) for the change should be given to the band’s two incumbent original members: Jeff Walker and Bill Steer.

(A brief note on Necroticism: a lot of Carcass fans say this is their best album, but bar two outstanding songs − ‘Corporal Jigsore Quandary’ and ‘Incarnated Solvent Abuse’ − I’ve always struggled to see it as more than a patchwork of brilliant parts which when put together gave the conceit of being ‘progressive’.)

When they reformed in 2008 and toured over the next two years, Walker and Steer retained the caustic flair that singled them out in 1993: Walker was sarcastic and Steer wore flares. This juxtaposition is no better demonstrated than in footage of their set at the 2010 Graspop Festival: Walker regales Belgium as ‘the land of chocolate and paedophiles’, Steer remains coolly enthusiastic in aviator shades and sports a yellow Les Paul which makes a mockery of his peers’ spiky guitars and widdly histrionics. This footage is made the sweeter by the fact that the bass guitar is right up in the mix. Walker has complained about the lack of audible bass on Heartwork, where the multi-layered guitars cover so much sonic depth and width.

If you want to understand how potent their sound was in 1993, listen to ‘Carnal Forge’, the second track from Heartwork. After a tumbling-down-stairs introduction the song erupts into a surging down-tuned barrage. Then Walker announces himself in that unique vocal style – somehow clearly enunciating through a gargling, rasping animalistic bark − and how’s this for an opening couplet: "Multifarious carnage/ Meretriciously internecine…" If you’re fifteen, as I was when I first heard it, it has you running for the dictionary in adrenalized fury.

But a minute in, Steer summons a complete mood change with a beautifully executed legato solo which somehow changes the emotional character of the song at a drop, before plunging you down again into the depths with piston-like repetitions, as the song seemingly tries to shake the interlude and re-capture where

it was before the breakdown, but not before opening out to a slow methodical chordal ascent and descent as the second guitar screws up the tension with a tightening figure, and it all races away again in a furious haze. It’s stunning, heady music, wrought with precision and intensity, as well as a Saturnine irreverence and humour.

If we choose to judge Surgical Steel on whether it captures Heartwork’s audacity, it certainly does that, and ‘Cadaver Pouch Conveyor System’ (one of many choice song titles on the album) emulates ‘Carnal Forge’’s mood swings: frenzied guitar runs; blasting, rhythmic turnarounds and a solo straight out of Steer’s Firebird repertoire, studied and stately over the pulsating backbeat. And again on ‘A Congealed Clot Of Blood’, after it breaks down into a passage reminiscent of the opening of Nile’s ‘The Black Flame’ (and if you want to hear another band that redefined death metal, their Black Seeds Of Vengeance album is for you!), Steer takes it down to a positively doomladen tempo to overlay another classy, slow-hand solo that introduces flavour and taste where most death metallers can only achieve bite and bombast.

Firebird is important here: Steer spent a decade playing and singing in his blues-rock trio after Carcass’ first demise, recalling Cream, Humble Pie, Trapeze and Grand Funk. It was a curious experience listening to Firebird’s 2010 Double Diamond album, made after the Carcass reformation, with a considerably hardened sound and almost NWOBHM stylistics. Steer has subsequently explained that he couldn’t help writing Carcass-style riffs and it was then that the black seeds of Surgical Steel were sown.

Other songs on Surgical Steel reflect Heartwork in parts, or more wholly: compare the striating melody lines and frenzied scales of the blast-beaten ‘Noncompliance To ASTM F 899-12 Standard’ with the opening of the track ‘Heartwork’ itself, not to mention the galloping main riff. ‘Master Butcher’s Apron’ has the same insouciant confidence of ‘Blind Leading The Blind’ on Heartwork with its bullish slowdown and groove-riff, although the latter features some insane jazzy, playing-in-reverse structures and dispenses harmonic minor scale theatrics in a single lick. These are much more laboured on ‘Master Butcher’s Apron’, but credit to new drummer Dan Wilding’s Lombardo-esque madman antics when it ups the tempo. If anything though the twenty year difference between these songs is testament to the incredible ability of Carcass to continue to shift speeds and squeeze melodies into thrillingly weird shapes: ‘Out Damn Spot!’ indeed.

And I don’t know many other examples of extreme metal lyricists quoting Lady Macbeth. Metal music’s lyrical concerns often draw on the archetype of the anti-hero raging against life, most obviously in the figure of the Miltonic Lucifer railing at a bland, repressive God figure. Walker addresses this elsewhere on Heartwork directly in the track ‘Embodiment’: "The effigy of flesh, corporeal Christi, nailed/ In submission to this false idol, seeking deliverance." This is a Carcass framing of craven Christian orthodoxy. Mel Gibson might have used it as a soundtrack for The Passion Of The Christ, a film if anything about extent of the damage a human body can endure before it is recognized as Godhead.

But ‘Arbeit Macht Fleisch’ speaks more directly to Carcass’ core themes, the title punning on the slogan at the gates of Auschwitz, ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’: "In this mechanized corruption line/ By mincing machinery industrialise/ – pulped and pulverized/ Enslaved to the grind." It’s (wo)man against the system, and acknowledges the band’s anarcho-punk heritage (of course, Steer was a core member of Napalm Death when they recorded Scum and From Enslavement To Obliteration), when – like now – the country was gripped by recession, conservative market forces and an indigent population. And it’s important not to forget that Carcass’ obsession with flesh is that they were vegan and vegetarian, even touring with their own catering.

Heartwork’s crowning achievement is that they introduced the blues into their portrayals of brutal machinery and technology, overlaid with what Walker described as ‘quasi-fascistic’ brutal statements of fact. Ironically Carcass grinded more on Heartwork than their supposed goregrind albums, but the sound was warm-blooded: the soul of a new machine. That said, the name of the album that is most oft-cited as the epitome of melodic death metal is Slaughter Of The Soul by Gothenburg’s At The Gates, released in 1995.

There’s nothing like the loping, twisted rhythm and melody of ‘No Love Lost’ on Surgical Steel, a curiosity even on Heartwork (not least because they actually managed to make a half-decent video for it). What Surgical Steel does serve up are some brilliant encapsulations of their grinding heritage and a refined death metal attack, most in evidence in the shorter, sharper shocks of ‘Thrasher’s Abbatoir’ and ‘Captive Bolt Pistol’. ‘Mount of Execution’, closing the album in the self-consciously ‘epic thrash’ style in which it begun, with its acoustic introduction and episodic transitions, might be the album’s boldest musical statement. Or might be the track where they sound most like… Arch Enemy: you decide! But the false-stop towards the end heralds the most ignorant breakdown of the album, harking back to the steady insolence of ‘Ruptured In Purulence’ from Symphonies Of Sickness.

Ultimately my love of Heartwork comes down to guitar tone: molten yet lead-heavy, offset by the cold mechanical precision of its grooves. In its eagerness to capture the band’s vicious shock-and-awe, Surgical Steel isn’t as successful. But that’s not really a criticism, because it’s a stunning assault: a band slicing a gaping wound in today’s moribund extreme music scene and darkly portraying the ‘Granulating Dark Satanic Mills’ of its country of origin.

If there was any justice attendees of Glastonbury Festival next summer would hear Carcass bleeding out of the John Peel Stage tent into Pilton’s fields, but there isn’t much justice in the world is there? And I think Carcass – the band that sings of the "cold, callous dignity of the mass grave" − like it that way.