I’m going to warn you upfront that the actual review content of this ‘review’ of a box set is woefully insubstantial. This is, in fact, probably what you’d call more of a think piece. However I’m guessing that you, dear reader, being a woman or man of exquisite taste, are already fully acquainted with these five out of the first six albums that Scott Walker recorded (as a solo artist) after the Walker Brothers’ initial split in 1967. This lovely box set doesn’t contain Scott Sings Songs From His TV Series which was released in 1969, the same year as the (now) revered Scott 3 and Scott 4. Which is ok, as it can be bought from most second hand record shops or decent branches of Oxfam for about four quid. It’s worth getting hold of it on vinyl to see a couple of big pictures of Walker, not quite yet awkwardly ready to emerge from his pin-up phase, wearing a large iron key on a chain round his neck. This is the key to the room he stayed in at Quarr Abbey in December of 1966, when the constant pressure of screaming fans camped outside his London flat caused him to go on retreat at a monastery, where he learned some vocal techniques related to Gregorian chant, a singing style that has informed some of his post Climate Of Hunter work.

The omission of this image alone is interesting, because his retreat (both spiritual and physical) to a lockable room on the Isle Of Wight, and the gossip and rumours that came in its wake, were perhaps the catalyst of the oft held perception that Scott Walker is a man barely holding it together. This all but groundless assumption that we are dealing with a man who would no doubt be stark staring mad by now if he didn’t have the gushing faucet of his "late period" albums with which to expunge his demons.

This perception stands quite patronisingly in opposition to the somehow unbelievable idea that Walker actually knows what he’s doing. (I say oft held; obviously he also has enough loyal fans to easily support his presumably costly sonic experiments, and a number of staunch supporters in the media as well; not the least of whom is Rob Young, who wrote the sleevenotes to this box set and also edited a great anthology of essays No Regrets: Writings On Scott Walker last year. Both make for excellent reading while whiling away an afternoon listening to all of these discs.)

The idea that you can plot a smooth arc on the graph of Scott Walker’s career, showing that he made a gradual transition from happy pop-singing teen idol to moody baroque hipster diarist and crooning existentialist to bonkers purveyor of violently avant garde experimentalism in clearly demarcated "periods" is demonstrably nonsense in my view. Discussing output alone, late last year on this very site, in terms of output alone, David Peschek masterfully dismantled this perception of the former Walker Brother with ease, pointing out that the influence of the avant garde exists in his music as early as 1967 if you care to look for it, such as on ‘The Plague’ the b-side to the 7" release of ‘Jackie’.

However, running a close second in terms of irritating myths that need to be debunked about the enigmatic performer*, is the idea that any of the changes in style that he’s been through are in any way related to a degradation of mental health. Even in papers and magazines that should know better, Walker is often painted as a "recluse" (he isn’t), as a difficult interview (he isn’t), as a distant or moody guy (he isn’t), or even worse, as twitchy and slightly psychotic (in my honest opinion, just because a guy wears a baseball cap indoors sometimes doesn’t make him a lunatic) and so on and so forth. And if no one out-and-out calls him mad, well, those are just the mealy mouthed times we live in – we know what all of those nudging, winking, baseball cap fixating descriptions are driving at…

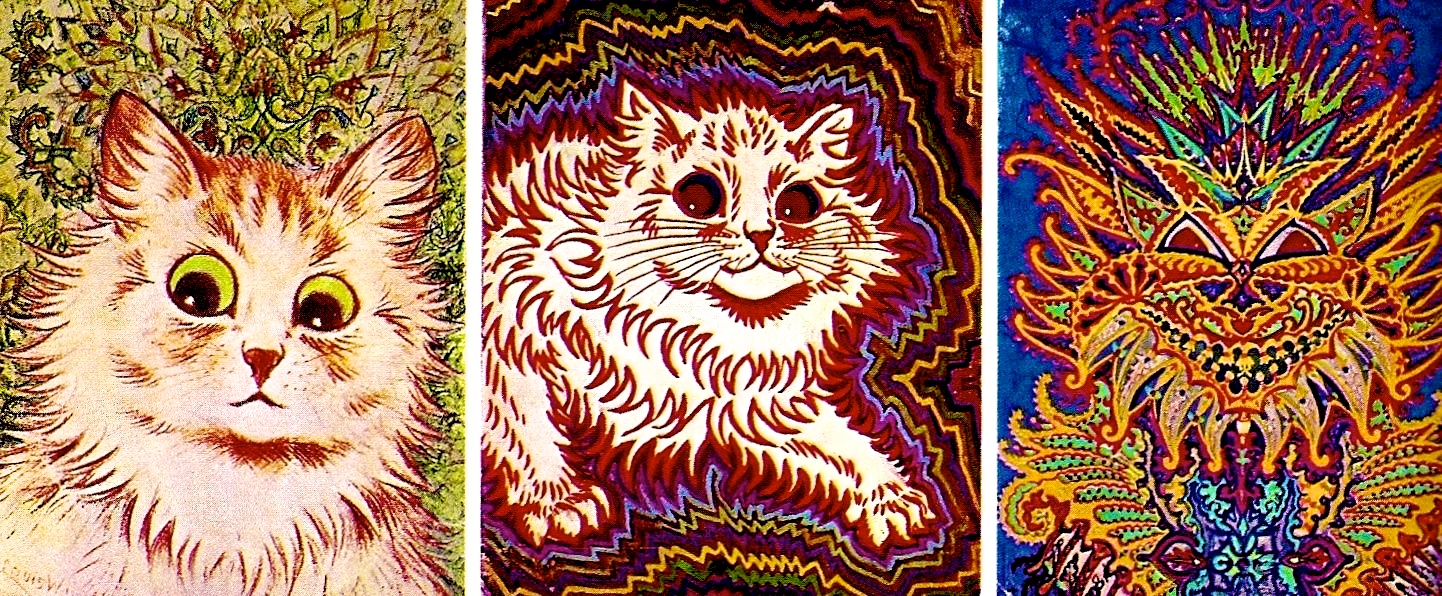

There used to be a moderately successful painter of animals called Louis Wain who was born in 1860 and died in 1939, some four years before Noel Engel (aka Scott Walker) was born. He was in some ways a man before his time, as ‘his thing’ was painting anthropomorphised cats with large eyes, sometimes in comic, cartoon-like situations. However, this is not why he is known these days. The popular narrative of Wain – one which I fully believed myself until reading up about him – is that he contracted toxoplasmosis, a cat-borne parasite, which drove him mad, making his paintings become more and more kaleidoscopic, fracturing into ugly psychedelic patterns and frightening jagged shapes.

Wain’s cats were regular fixtures in psychology textbooks when I was young, ‘demonstrating’ vividly a man’s ‘descent into madness’. However, this theory has more holes in it than a fishing net. For starters, there is no proof that Wain was actually insane. While he did spend some time in a couple of asylums because of "erratic and violent" behaviour, once transferred to a nice hospital in the home counties after intervention by celebrity supporters his behaviour improved immeasurably. But more to the point, his actual painting skill never actually deteriorated, as one would presume. In fact, in some ways it got better. This suggests that he perhaps had Asperger’s Syndrome rather than schizophrenia – which would explain a heightened sense of detail. Plus, it seems that the terrifying psychedelic patterns that loom behind some of the cats in his later work are actually designs that were found stitched into his mother’s sofa, rather than imaginary fractals looming out of the corners of a padded cell. Add to this the fact that some ‘kaleidoscopic’ effects can be seen in work he completed 20 years before he was committed and the fact that, right until he died, he continued painting ‘standard’ pictures of cats, then the narrative seems to crumble into nothing. In fact, the popular perception of Wain seems to stem from nothing other than the cynical manipulation of an ambitious young psychiatrist (Walter Maclay), who purposefully selected and ordered out of chronology certain of Wain’s paintings to back up his theories on psychosis.

It was the kind of narrative that thrives and still does. Who wouldn’t want the fantastic story of a painter driven mad by the very thing that he loved and had brought him fame? Whether feline portraitist driven mad by a cat-borne parasite, plagued by demonic visions of the animals he once loved; or perhaps a pop singer driven mad by fame and fortune, psychotically smashing away at the talent that ruined his peace of mind, until nothing but jagged pile of dissonant shards remained? Tempting – but bullshit nonetheless.

I know it’s not that exciting, but isn’t it about time that the popular narrative started considering the period between 1967 and 1970 not as the time where neurosis first began to show, but instead a time of galvanisation; when he first began trusting his own instincts over those around him? When he first started putting artistic and aesthetic considerations firmly before his and his record label’s commercial needs; not a smooth arc admittedly, but still an ongoing process which he is clearly still engaged with, and one I hope he never abandons. As Rob Young reminds us, it was Walker himself – in the sleevenotes to Scott 2 – who publicly expressed a desire to break with his former working methods, castigating himself: "It’s the work of a lazy, self-indulgent man. Now the nonsense must stop, and the serious business must begin."

Reviewing Scott through Scott 4 and ‘Til The Band Comes In thoroughly here in 2013 is a fool’s errand, but that won’t stop me from stating the absolutely obvious: these albums are absolutely fantastic and all deserve to be heard and enjoyed. Three is my favourite but the critical consensus seems to have gelled round Four. Is it odd that they’ve included ‘Til The Band Comes In? Marginally, perhaps. Whatever. Brothers and sisters, if for whatever crazy reason you haven’t heard the albums contained in this collection, you need to rectify. Rectify and you will not regret.

But finally, if we can first hear Walker’s very own "kaleidoscopic" effects on ‘The Plague’ in 1967, then surely these five discs must be bristling with uncanny sounds, off kilter instrumentation, bizarre production techniques and disturbing lyrical turns? Well, ‘bristling’ would be overstating the case, but they are noticeable throughout.

On Scott One, for example, we hear the first really blatant example of his blossoming love for György Ligeti, an influence that can still be heard today on his latest album Bish Bosch, released last December. But also on ‘Montague Terrace In Blue’, beyond the confident, artistic hipster statement of the title, there are the lyrics which go beyond the rawness of a Jacques Brel enthusiast or kitchen sink scribe. These lyrics transport the listener into the realms of the genuinely uncanny: "The little clock’s stopped ticking now / we’re swallowed in the stomach room / The only sound to tear the night / comes from the man upstairs." In a sharp bit of existentialist and imagist lyricism, the tenement itself temporarily becomes an unnamed beast devouring its unfortunate inhabitants.

A "flashforward" to future weirdness makes its presence known on ‘The Amorous Humphrey Plugg’, not so much lyrically in its slightly self-conscious homage to T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Lovesong Of J. Alfred Prufrock’, but in the strange, sky-scraping upward swoop of the violins two thirds of the way through, which adds a subtle hint of neurosis to the otherwise slightly cartoon-like depiction of the drunken protagonist. This hint of hysteria is revisited in the string accompaniment to ‘Plastic Palace People’, which Walker arranged himself. The composition (and its really odd use of double tracked, delayed and distorted vocals) is counter-intuitive, and despite being a slight detail rather than a dominant feature of the song, alters the overall effect dramatically before you even get to the bone-chilling lyrics, which mimic jogging down a never ending spiral staircase in a childhood nightmare.

And just in case you were still wondering, the gloves come completely off on Scott 3. The strings that accompany ‘It’s Raining Today’ are exquisite, and some comparison between this and later work on Climate Of Hunter and Nite Flights simply can’t be denied. His songwriting really blossoms on this album, with his own compositions such as ‘Big Louise’ really standing out. But it is co-work with Wally Stott that really helps flesh such tracks out, dressing the lyrics to add a psychological depth and a sympathetic and vibrant warmth to the picture they paint.

On Scott 4 it’s wall to wall espresso sipping, Bergman watching, Morricone-listening, existentialist musings on dictators and such like. But amid all this, special mention must be made of ‘Boy Child’, a berserkly futuristic-sounding slice of genius (again worked on by Wally Stott) that sounds like a hymn sung on the end of all days. The unsettling opening orchestral ‘Prologue’ to ‘Til The Band Comes In raises the listener’s hopes for the uncanny, the weird and the kaleidoscopic perhaps slightly too high. (However, to say that this album is 100% compromise and creative backward step is wrong; flickers of the unconventional can be detected in the weird double tracking of the orchestral accompaniment on the title track, for example.) This album does contain what Quietus writer John Tatlock calls Walker’s "most batshit crazy" song to date, ‘Jean The Machine’. It is, however, crazy in the worst, early 70s sitcom theme music style possible. Ah well, can’t win ’em all.

*Jesus, I’m doing it myself…