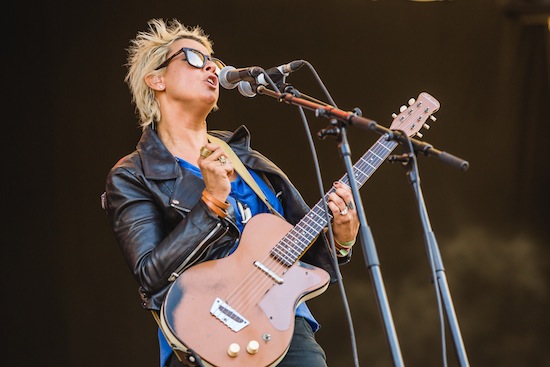

Photograph courtesy of Pooneh Ghana

Latitude is a nice festival

…and that isn’t meant in a disparaging, damning-with-faint-praise way; it’s just very attractive, in a nice way. The sprawling legions of organic food vans, the lovingly-decorated, neon-lit stages in the woods, the way the setting sun swells through the trees… if you were a linocut artist, hey presto, you’d have the cover of a Penguin collection of poetry about the Suffolk countryside in the bag. The niceness even extends to the sponsorship at the festival. When we get there, a Marks & Spencer tent is set up outside the main gate. Outside it, a man bellows into a microphone, delivering announcements between the songs coming over a tannoy. “Who’s had a walnut whip?” he shouts, though to whom the question is addressed isn’t immediately clear nor, indeed, is whether there were ever any walnut whips on offer. Nevertheless, the fact that it’s a snack from the higher regions of the chocolate shelf as opposed to a scroggy bag of chips or some sweaty Carling cans that’s in question sets the bar for the weekend.

Crowd surfing is prohibited, but wave all you like

Photograph courtesy of Jessica Gilbert

One of our first stops is artist David Shrigley doing some faintly offensive portraits in the Film And Music Arena, but it’s soon time to leave for Tim Burgess on the Obelisk Arena main stage. The bruised strength at the heart of ‘Tobacco Fields’ seems more poignant here, in counterpoint to the unobstructed sun, before Burgess rolls out a brilliantly sparse version of ‘The Only One I Know’, its Hammond organs jettisoned for bare bones acoustic guitars, with the lyrics roaming in new-found space. By this time, Burgess has been dealing out a few waves to the crowd, many of who greet him like an old friend. Pretty soon, it seems like everybody wants in: "I like all the waves… Look, there’s some more over there!" he says as the outbreak spreads, and he begins working overtime to meet demand from the rapidly fluttering hands.

Cat Power’s Chan Marshall gamely picks up the waving baton later on, giving us some friendly hand-scrunching when she comes on stage, clasping a mug of tea and awkwardly rearranging her mic stand. This slight uncomfortableness carries through the entire set, a residual glimpse of the stage fright that’s plagued her before, but now it tempers the set with a faltering sturdiness. If anything, she seems more confident than ever, opening with ‘The Greatest’ and turning it on its head. On record, it’s a languid ode to accepted failings, piano-led and gently gilded by violins; now, based around a spindly guitar, it builds gradually into a gargantuan torch song, every drop of pain wrung out. From hereon in, the intensity sustains, with tracks from last year’s Sun ‘Cherokee’ and ‘Manhattan’ revolving around the emotional chest-kick that is ‘Metal Heart’. By the time Marshall departs, having thrown bottles of water and flowers out into the crowd, there’s a tangible sense of loss, a feeling that that was a one-off.

Photograph courtesy of Danny North

Bo Ningen should play every hour, on the hour through the night, embedded deep within the woods

But instead they’re on at 3.10pm on Saturday afternoon. In fairness to Latitude, everything runs like a supremely well-oiled machine throughout, but its family-friendliness means that everything errs on the early side. Bo Ningen, it feels, get the worst of this. Their collision of acid rock, primary coloured robes (just the one on this occasion) and flailing hair is no less visceral than usual, but feels like it would be more at home cloaked by the night. That said, the band totally and utterly slay. Four songs in, they declare that it’s time for their final number. The heads that have been banging across the crowd are momentarily thrown, but, as it transpires, that song is the 20-minute-long piledriver ‘Daikaisei’. Mon-Chan is an unbelievable powerhouse of a drummer, Taigen Kawabe flips from banshee screech to silently-mouthed incantation and Kohhei Matsuda transfigures his guitar to wield all manner of ungodly feedback. It’s hard to shirk the feeling that this slightly palls Yo La Tengo’s long-form songs on the main stage the day before, all of which ended with Ira Kaplan going down fretboard wig-out cul-de-sacs; if you’re going to do a guitar solo, why not make it sound like the last-gasp transmissions of a dissembling ISS sieved through a black hole?

… in fact, if you want the good stuff, head to the woods

As much as it sounds like a venue Enid Blyton never christened, The Faraway Forest, as well as the i Arena, host some of the best acts. Saturday morning opened up with Drenge’s Eoin and Rory Loveless on the latter. On record, their dead-eyed, dirt-flecked grunge sounds pissed, but live it’s howlingly abrasive. Eoin wrangles with the riff of ace debut single ‘Bloodsports’, while Rory’s drums wrap out the martial shuffle of its B-side, ‘Dogmeat’. There aren’t too many words spoken between songs, but there’s no need: the bristling, rough-cut sounds the brothers pull out of their instruments say enough and end up cutting them out as one of the most ferociously singular-sounding bands to emerge this year.

Later in the day, Serafina Steer is on the same stage, taking pretty much the opposite tact: she talks nervously between songs, excusing her harp’s new string for an (inaudible) bum note, before realising "no need to draw attention to it" and later taking to a keyboard, telling us: "I’ve changed the sound of this without telling anybody – this is the cosmic flute sound". It turns out the cosmic flute isn’t so much astrally wondrous as charmingly crumby, but Steer’s voice and everyday minutiae lyrics make a virtue of it.

On the other side of the festival, there’s a queue to get into Neon Neon and National Theatre Wales performing the play they’ve written around the recent Praxis Makes Perfect album. Following some avoiding of glances that come after a confident flash of press tent wristbands get us precisely nowhere, we do eventually get in, allowing us to make the valuable insight:

Gruff Rhys is partial to a good conga

The play charts the rise and fall of the 20th-century left-wing Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli and we come in at the point where Soviet soldiers are trying to regain a manuscript he’s smuggled out of Russia, before he hits the town on getting to Milan. Both occasions give the actors (and Rhys, taking a momentary break from singing duties) leave to run around snapping at books and balloons, slapping stickers on audience members’ faces and generally making Feltrinelli’s life seem like a bit of a hoot. (Credit, too, should go to the play for bringing to light Fidel Castro’s uncommonly fine basketball skills). At the end of the play, one of the actors reads out the results of a poll taken to find out whether the crowd support or oppose the monarchy; when it turns out they’re heavily against, guest Asia Argento (already one bottle of wine down) surprisingly gives us all the finger, though it seems everyone takes that as a gesture of support and heads off on their way.

Wahey! There’s a satellite coming towards us!

It’s hard to say anything about Kraftwerk that hasn’t already been said much more eloquently before, but Saturday night’s headline show is expectedly brilliant. The sound loses nothing for being in a field, the drum machine kicks hitting straight to the sternum, and the songs, ‘Computer Love’, ‘The Man Machine’, ‘Radioactivity’, ‘Trans Europe Express’ generate the kind of exultant joy that only Kraftwerk can. It’s a feeling that finds its expression in occasionally bursts of wild cheering that seem, once, to generate a flicker of a smile from Ralf Hütter, but elsewhere people just seem to get off on the 3D visuals (it’s fitting that Kraftwerk should make themsleves an immaculately uniform field of polarised glasses-wearing punters), nowhere more so than when Falk Grieffenhagen’s satellites threaten to poke eyeballs in ‘Spacelab’.

Photograph courtesy of Danny North

Laura Mvula’s husband may not like her music, but we do

With a well-placed spot opening up the BBC 6 Music stage on Sunday morning (taking on a secondary purpose as balm for Tuborg-ed out heads), Laura Mvula deals out her set like a seasoned pro. The vocal harmonies on ‘Like The Morning Dew’ and ‘Let Me Fall’, which Mvula has to play, she explains, because it’s "the only song I’ve written that my husband likes", are rendered in sonic Day-Glo, and even when they go a bit awry on ‘She’, Mvula’s own voice cuts through like a clarion call. She’s an infinitely polite performer, thanking us profusely after every song, which gets reciprocated when the crowd take up the hand claps that beat out the rhythm on ‘Green Garden’, running right the way through and still going even after Mvula leaves the stage.

Seattle, Los Angeles, Southwold, it’s all the same for Foals

Last time they played Latitude, Foals headlined the second stage a little sullenly, having to stop momentarily to ask the front rows of rowdy teenagers to calm down. Now, with this year’s Holy Fire album repositioning their spiky math rock origins within a stadium-trouncing backdrop, the band approach their slot topping the Obelisk Arena with a new vigour. Lights strafe the crowd to begin with, before the lone figure of Jimmy Smith arrives to strike up the spine of Holy Fire opener ‘Prelude’, then gradually joined by his bandmates, Yannis Philippakis bounding on stage last. It’s a deft statement of intent, the guttural roar of fuzzy power chords and synth swells massing up into an iron-cast wall of sound to match the searing light-glare from the stage. “Thank you… What a day!” shouts Philippakis after ‘Total Life Forever’, the first of a clutch of numerous positive, hyper-pumped interjections he delivers while catching his breath. "Let’s do this thing! Oh man!" he says, before Jack Bevan kicks in, joined swiftly by Walter Gervers’ bass, getting the biggest cheer so far for signalling ‘My Number’. Philippakis’ enthusiasm is catching and the band are so preternaturally tight it’s almost physically tiring to watch. So much so that when ‘Spanish Sahara’ fades in, the momentary repose it affords serves only to underline the grandeur of the track’s slow-burning scope, simultaneously uniting the field and crushing any fears the band had about taking the top slot.

It’s rotten in jail (so, praise be, we’re in the literary tent)

Following a closing round from Beach House, whose ‘Wild’ and ‘Lazuli’ take on a sort of luminous sonic glow in the final throes of the festival’s music, as well as a midnight screening of A Field In England (here’s a laugh: get some sleepy festival-goers in a darkened room, start playing a film and then watch them wake in abject terror when said film turns to Reece Shearsmith munching magic mushrooms and screaming: “I SHALL CONSUME ALL THE ILL FORTUNE WHICH YOU ARE SET TO UNLEASH!”), we stumble onto a late highlight, a poetry club hosted by Keith Allen in the Literary Arena. John Cooper Clarke’s Salfordian tones slice out of the tent: “Getting grief from a terrorist who says I’m a moral derelict/ He’s an armchair psychotherapist, nobody likes a clever dick/ Rotten here in jail”. As ever, the words, running into each other, sneaking out with machine gun speed and steadiness, are entrancing, even more so when matched up with Clarke’s almost non-existent frame and impenetrable sunglasses. Sadly, we’re too late and he’s onto his last poem, but Allen pops up and wants to thank all his poets by bringing them back onstage to be serenaded by his band, decking them all out with a “sexy motherfucker” from his singer. Once Clarke (a little taken aback by his new appellation by the looks of things) and the other sexy poets have been given their dues, they’re off, as are we, back into the woods.