As the Second World War recedes from memory, our relationship with it become more ambiguous. SS camp guards may rarely have resembled Kate Winslet, the Rose of Reading (bad pun intended), but it’s no longer seen as a simple battle of the bad guys in the good uniforms versus Fred Karno’s Army with upturned soup bowls on their head (which in fact offered better protection and made an ideal stew receptacle, even if the Hells Angels said ‘nein’ to it). We are now perfectly aware that Stalin was as murderous as Hitler, although better at fighting wars, and how supposedly liberal Holland packed off proportionally more Jews to death camps than any other occupied country (even as the Dutch produced the excellent gallows humour one-liner ‘keep your filthy hands off our filthy Jews’). And that the Europe that emerged from the ruins is a very different place, albeit one created by the collaborating classes who didn’t care to be reminded of their dirty pasts. No wonder Jonathan Littell’s second novel (if you count a spot of cyber-juvenilia penned in his early twenties) written in French by an American, won the prestigious Prix Goncourt and has sold close to a million copies in France alone. Serious, unashamedly literary and ever so transgressive – this is the stuff publishers love.

The Kindly Ones consists of Maximilian Aue, a former SS officer now running a factory in France, recalling just what he did in the war. Although that’s like the immortal description in Halliwell of a mediocre American movie of War and Peace – ‘the adventures of a Russian family during Napoleon’s invasion’. This one thousand page brick of a book is magnificently self-conscious and frankly bewildering, a brutal satire of everything from historical epics to management speak to spin doctoring – the title refers to the Erinye, the original ‘rebranding’ of the rather less friendly Furies of classical mythology. Don’t expect many jokes though – Aue hiring a factotum called ‘Piontek’- Polish for ‘Friday’- is about as good as it gets. Littell even insists that all versions include conversation in blocks of text, rather than conventional punctuation. He wants his readers to suffer.

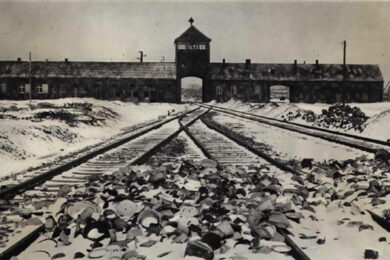

The half-French Aue grows up too stupid to understand the rules of football. Inevitably the black shirted referee lurking within him is drawn to the law and on to the SD, the ideological heart of the Nazi machine. Sodomy and incest are mere hobbies in comparison. He is of course a cipher, an implausible and symbolic figure who turns up in historically appropriate situations (the Babi Yar massacre, Stalingrad, Auschwitz, Berlin bunker under direct attack) or places known to the author (the Caucasus where he worked as an aid worker, Provence where he grew up) and can recall every single conversation in detail that would shame a court recorder.

Anyone familiar with Curzio Malaparte’s Kaputt, a WW2 atrocity travelogue penned by a well-connected Italian journalist (who apparently changed his stance when it became obvious his team wasn’t winning) will recognise Littell’s method (Personally my favourite example of the omnipresent narrator is Jayne County’s splendid autobiography Man Enough To Be A Woman– Wayne/Jayne is present at Woodstock, Stonewall, Max’s, CBGBs and anywhere else where non-genocidal transgression happens, and no one gets shot in the back of the head, although bartender, wrestler and erstwhile singer Handsome Dick Manitoba does endure a mike stand round his bonce)

Wherever massacres are committed old Max Aue is there with his clipboard, making sure that the proscribed procedures are being followed and that every dead Jew, or other untermensch is correctly recorded. But Max is a stickler – only true Jews end up in the flue. The Bergenjuden of the North Caucasus are spared after he pens a lovingly detailed report on their origins (and the locals spiritedly fight the invaders).

Historical figures pass through, some as obvious figures of fun. The French writer Robert Brasillach, friendless, naïve and later shot as a collaborator, is cruelly and accurately described by Aue as “the boy scout of fascism”. Adolf Eichmann, chief bureaucratic organiser of the Holocaust, turns up as a nervous middle manager suddenly empowered by possession of an unlimited company credit card. Heinrich Himmler considers Aue rather pedantic, but does like his eugenics suggestion lifted from a pulp science fiction comic.

The German critics didn’t like The Kindly Ones. Their translation was criticised partly for alleged historical inaccuracies – hardly crucial, this is Sven Hassel with acronyms at times – and because though multi-lingual, Littell doesn’t do Deutsch and therefore wasn’t up to speed with the latest in recently uncovered war memoirs. One reviewer took issue with the dedication ‘pour les morts’, suggesting that this was so glib that surely he had to be referring to the generally un-commemorated SS men. (Littell, though non-observant and suspicious of Zionism, is in fact Jewish enough to have been murdered under Nazi doctrine)

Their present-day sensitivity is understandable, but were pre-war Germans especially stupid, one wonders? Aue carefully explains his justifications, at no point questioning the mass murder of millions who shared little more than a religious tradition and a taste for education. Had not so many died for them they might be simply laughable. His straightforward sister/lover, the faintly drawn Una, instead wonders why if the Jews are so powerful they find it so hard to save other Jews. A captured and condemned Soviet Commissar literally borrowed from Vassily Grossman’s Stalingrad epic Life and Fate tears apart National Socialist theory as a perversion of Marxism (rather obviously spelling out its inevitable doom at Stalin’s hands).

Littell, whose father, thriller writer Robert, moved to France rather than live under Nixon, has said that he wrote this book partly out of fear that in similar circumstances he could have behaved like Aue, in the service of the atrocious, wondering what he would have done at My Lai. Yet, as many historians have pointed out, only the Soviet and Nazi armies actually took the war seriously enough to regularly shoot at each other, largely due to the fear of a bullet in the back from their own side. In the West, estimates suggest that no more than one in ten, perhaps one in twenty of British and Americans aimed to kill, preferring to survive instead. The destruction of even the least important German towns when they refused to surrender is testament to the warped ideology that glorified death and war over good old plunder and pillage.

As this insane, insanely long novel plods on, endlessly detailing intra-departmental rivalries while the RAF and USAAF bomb Berlin to rubble, it becomes ever more compelling and hallucinatory. Aue sodomises himself with a stick in the Pomeranian wood where his sister resides (she’s away), sneaks through Soviet lines evading gangs of feral children, is pestered by two coppers/furies who want to talk to him about the murders of his mother and stepfather and, memorably, bites Hitler on the nose while receiving a medal, earning himself a damn good jackbooting from everyone else present. Eventually he pulls the old Trainspotting switcheroo and flees Berlin. It’s as close as this wild, demanding book comes to the conventionally cinematic – no wonder Littell has already said he won’t allow it to be filmed for fear of glamorising evil.

The quirky KC Reginald Paget, who chose to defend Field Marshal von Manstein from charges of war crimes, also dealt with the SS economic theorist Otto Ohlendorf, another character who passes through The Kindly Ones. Ohlendorf’s death squads murdered many civilians in the East and he happily admitted his guilt. Yet when Paget investigated he realised that his claims had been hugely exaggerated to please his superiors. Making up figures to please the boss and secure a bonus – that is the horrible reality of the vile penpushers let loose by Nazism. Though Littell presumably didn’t intend it, this demanding, sprawling lump of a book is more relevant than ever.