Growing up in Ethiopia, the musical path was not one the young Mulatu Astatke was expected to go down. Instead, in the 1950s he went to high school at Lindisfarne College in north Wales to study aeronautical engineering. While there he had the chance to pick up musical instruments, and discovered he had a natural talent. He soon moved to pursue his interest in music at Trinity College of Music in London, where he studied clarinet, piano and percussion and recorded with Guyanan singer Frank Holder.

"I started taking music myself," he says. "I went to Trinity College in London and studied classical music, and that is where I found myself. They found I had the talent. My musical experience started here." He then moved to the United States to study music at Berklee, Boston, where he was the first African student. Here he learned about arranging and composing, worked with big bands and took up the vibraphone. "And of course there was jazz," he adds. "At Berklee I had a very interesting teacher who said, ‘Be yourself’. So I went to Berklee and became myself, by creating the music, Ethio jazz."

This new music, Ethio jazz, combined traditional Ethiopian pentatonic five tones with twelve from American jazz, using folk and Coptic church melodies with Latin and Afro rhythms to make jazz with an Ethiopian twist. Although the twelve tone diminished scales were introduced to jazz by the likes of Charlie Parker for improvising, Astatke points out that Derashe tribes in southern Ethiopia had been playing these scales years beforehand.

Following his degree at Berklee, Astatke moved to New York and developed the new sound he had envisioned with his group Ethiopian Quintet. "We had some American musicians and some Puerto Rican musicians involved in it, and a different feel, different arrangements," he says. "That’s how I did something different. It was a great opportunity for me. It was great and they were really great musicians and they really loved what I was composing, loved what I was doing, and how I was playing vibes at the beginning. After that I worked upstate New York, and played all different places, making three different albums – The Afro-Latin Soul Volumes 1 & 2, and the third was Mulatu Of Ethiopia, released in 1966, a long time ago. It was all recorded in New York."

Having returned to Ethiopia in the late 1960s (with the first Hammond organ and vibraphone his friends back home had ever seen), Astatke enjoyed success during the latter years of the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie. After Selassie’s death, Mengistu’s corrupt Marxist regime ruled between 1974 and 1991. However, Astatke insists this did not harm his career, and he continued performing throughout. In the late 90s there was a resurgence of interest in Astatke’s songs after they were showcased on the album Éthiopiques, Vol. 4, which was dedicated solely to his music, and part of a larger series featuring many of Ethiopia’s best known musicians. He reached a wider audience still when Jim Jarmusch used several of his tracks in his film Broken Flowers in 2005.

Last year Astatke was awarded an Honorary Doctorate as the first African at Berklee. "I see this doctorate, not for Mulatu only, but this is a recognition of African music and fellow African musicians, while giving so much for the development of music," he says. In 2007 Astatke was awarded a fellowship at Harvard University, allowing him to experiment with developing traditional Ethiopian instruments like the krar, adding strings and developing new tones, to create new musical possibilities and provide an alternative to western instruments like the guitar.

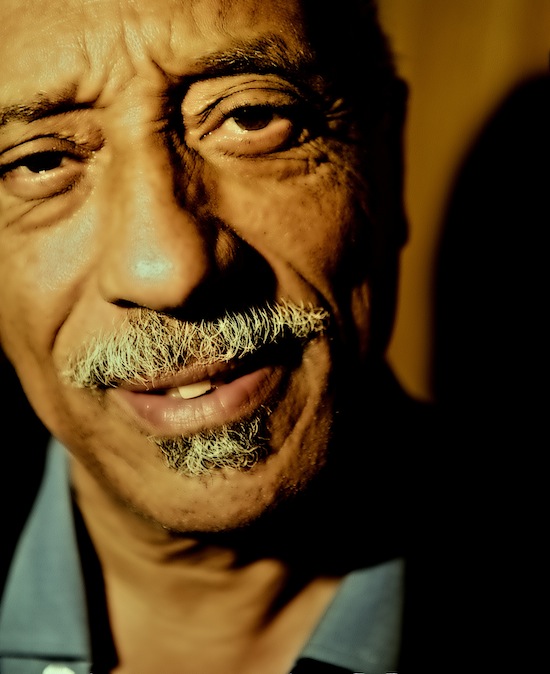

Mulatu turns 70 later this year, and another work in progress is his Yared Opera, highlighting the importance of what he calls Ethiopia’s contribution to world music, the conducting stick. The project is being made in cooperation with a choir from the Ethiopian Coptic Church, and Astatke hopes to get the production on stage soon. A new album is also in the works, and Astatke was giving final approval to the latest mixes before mastering as the Quietus met him in London to discuss his career.

Taking Ethio jazz back to Ethiopia

Mulatu Astatke: When you branch out I think there is a responsibility to share with other people after you get back from studying, experimenting and learning. I really wanted to share this experience with the musicians in Ethiopia and the Ethiopian audience. After that I went to Ethiopia, and of course it is a bit difficult in your heart, because playing new music to people, usually, is dangerous. So, it was very hard work to put this music to people, because it is a different type of music.

In Ethiopia, before I came back, we had conductors, composers, big bands with trumpets, saxophones and trombones, and they play Ethiopian music, it is a different way they are doing it. When I came over it was a different approach to Ethiopian music. We used improvisations, the Ethio jazz feeling, the different harmonic structures, voices, counterpoint work. All this was the ingredients of Ethio jazz. It was difficult at the beginning, but now… Ethio jazz is BIG! That’s not only in Ethiopia, but all over the world it is big now.

Meeting John and Alice Coltrane and working with Duke Ellington

MA: Those people you just mentioned, they were my heroes before. I really respect [John] Coltrane, Miles [Davis], Duke Ellington and Alice [Coltrane]. Alice came over to Ethiopia as she was involved with a trance, meditation movement, and they opened an office in Ethiopia. However, they didn’t know jazz very much. So I knew her, it was so great. I introduced her to Ethiopian musicians and we played together and she recorded at radio stations in Ethiopia. It was a privilege. And when Duke Ellington came over I had the opportunity to meet him and also write an arrangement for his band to play Ethio jazz. I was actually featured at his concert at the Hilton Addis, which is my really great moment in my life. It was so beautiful to just stand next to Duke and play my music with his band playing. It was so great, I really, really enjoyed it. It was so fun.

How African-influenced jazz became incorporated within the new style of Ethio jazz

MA: I studied this music about 40-something years ago. You see all kind of elements in Ethio jazz. Jazz is one of the elements. But also, for my music based on five notes music, I have four different modes. You will compose our music within five notes only, so my music is a fusion between five and 12 [notes]. It is very high tension music, very sophisticated music. When you are combining both you really have to be careful that you do not lose the feel and the touch of the five notes. So that is how I managed to fuse both and come up with some different sounds, different kinds of things. That is how Ethio jazz was initially informed and came up. It took a while, it took many years, but finally it took off.

The ‘golden era’ of Ethiopian music, in the late 1960s and early 70s

MA: I don’t understand what is the ‘golden era’, because every time, everywhere is golden to us, so I don’t know why they call that the golden era. Because we still have big bands, we still have symphony, classical music, we have the music schools and it’s okay, but we also produce a lot of young talent now in Ethiopia, radio programmes, jazz, recorded music and other music as well. So I don’t know why they call it a ‘golden age’. To me music is always gold, all the time, any time, everywhere.

How music making in Ethiopia changed following the end of Emperor Haile Selassie’s reign in 1974

MA: For me it was no problem. I was actually doing what I am doing now. I was traveling and I was playing, and I was also a board member of the International Jazz Federation.

But there was some restriction. For me, nothing very much. It was only that the musical atmosphere was different than what it is now. Now we are freer, you can do what you want to do, sing what you want to sing, play what you want to play, travel and go out. Now we are freer, but there were some restrictions at that time.

The People-to-People tour in 1986

MA: Well, that was a really beautiful experience for the promotion of People-to-People. Number one: there was a drought in Ethiopia, so the Ethiopian government organised the tour for the promotion of Ethiopian culture. I did all the music and arrangements. It was all involved with Ethiopian culture, musical instruments, dancers and singers, and it was a beautiful experience. So it was one hour, an hour and a half of music. It was so beautiful. We went all over the world to say thank you to those people who helped us during the drought.

We even came here [to London] and played at the Barbican, and we played everywhere, man. We played Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, Germany, we played the Lincoln Center in New York, we played the Kennedy Center in Washington. First class. I was so happy to show the richness of culture Ethiopia has to the world. And we showed that, with the clothes, the musical instruments, the dancers, from north, south, east and west. I enjoyed it, I tell you. We went to Havana in Cuba, we played Hungary and Bulgaria, we played in Sweden, Germany, England, Paris, all over the world. And it was really a great and beautiful opportunity to show Ethiopian culture to the world. I loved it so much, I had a great time.

Éthiopiques, Vol. 4: Ethio Jazz & Musique Instrumentale, 1969-1974 released in 1998 and the film Broken Flowers in 2005

MA: Éthiopiques was big. And it was so great. There were a series of volumes of Éthiopiques, done by Buda Records in Paris. This also helps release my music. But more really, the film Broken Flowers.

I tell you, that film was all over. The film was all over the world and it was big also. It helped for my music, and I like the music lovers it brought, but I also got more of an audience from the film goers coming to my concerts. In New York I was playing in a place called Joe’s Pub, only sixty people were there. I played at the Winter Garden in New York, and they were all so young, beautiful concerts my friend. So this music was suddenly just boosted all over the world.

Director Jim Jarmusch’s secretary called me up one afternoon at the hotel I was staying, and said: "We are coming tonight to your concert. Jim and the whole crew are going to come and see you this evening at the Winter Garden." So I said: "Great, just come over." So he came, he liked what we did, and then after we finished, he came backstage and we talked with him. And he said: "Mulatu, I have been a fan for years and years, so I have seen you and I want to talk to you." And I said: "It is great meeting you as well." He said: "I have some ideas. For my next film I want to use your music." So I said: "Go ahead." And then after a few months he emailed me, and that is how the whole thing started and happened.

How collaborating with the Heliocentrics on the 2009 album Inspiration Information offered a new direction

MA: It was great. They were great musicians, nice guys, really nice to be with. And the main thing was also they loved Ethio jazz. All the musicians loved that music, so we really enjoyed playing together. The type of instrumentation is electronic, acoustic, that kind of thing, which is a different direction to Ethio jazz. It was so great, beautiful. So, we enjoyed ourselves, we played together and we did a CD and it became very successful. It was another big development of my music.

Another progression with 2010 album Mulatu Steps Ahead, and a new album soon to arrive

MA: Mulatu Steps Ahead was more acoustic, more how I wanted to hear Ethio jazz originally, that is how you want it. It’s beautiful. I really enjoyed it. The next one should be out in a month or two. It’s a CD called Sketches Of Ethiopia. I think you will love it. Fatou [Fatoumata Diawara] is featured on one song. She is from Mali, which I think is so beautiful – that east meets west of Africa. I hope it will be successful in the world – I just keep my fingers crossed.

On this one there are all experimental Ethiopian cultural instruments evolved together. And that was the structure. So you will hear all kinds of Ethiopian feel within this music, that’s why I called it Sketches Of Ethiopia, with music from different parts of Ethiopia.

The Yared Opera

MA: That is the next one I am working on. The aim is to be able to finish that and get it on stage. It is about conducting. We have a stick we call a mekwamia in Ethiopia. That stick was used to conduct music in the 6th century – and in the 6th century there were no symphony orchestras in the world. So the movement and the system of how they were conducting – if you see the military band march, and the man going in front waving sticks and things – 80-90% of that movement is from mekwamia in Ethiopia. Those basic movements of a conductor – they’re from the mekwamia. Conducting is Ethiopia’s contribution to the world. And I am sure this is true, because there was no conductor, there was no symphony, but we were conducting.

Developing Ethiopian instruments in new ways, such as adding strings to the krar to create extra tones

MA: You know, that instrument [the krar] has been limited for centuries and centuries – the musicians we call the azmaris can only play four modes and five notes. So I managed to upgrade the strings from five to eight strings. And I managed to play several songs, including ‘Guantanamera’, ‘Mercy Mercy’ and ‘Summertime’ on the krar. And then I managed to replace European musical instruments, changing the lives of the azmaris, bringing the azmaris to the 21st century. That was the problem. So I was still working on it. To complete it, I had the chance to go to my team in Boston at this great laboratory. We have been working with some great scientists to develop it. So very soon I will continue with that – after the opera, I’m going to do that. And the whole idea of the Ethio jazz will be to play with all developed Ethiopian musical instruments – without piano, without trumpet, without saxophones.

Mulatu Astatke is on tour around Europe this summer, including an appearance on The Quietus’ stage at Field Day on 25 May. The full list of dates runs as follows:

MAY:

24 – Barcelona, Primavera

25 – London, Field Day

JUNE

5 – Amsterdan, Pitch Festival

JULY

20 – Chanac, Festival Detours du Monde

25 – Nyon, Paleo Festival

28 – Fujirock Festival

AUGUST

2 – Leuven, Midzomer

3 – St Nazaire, Les Escales

10 – Paris, Trianon