Listen to our special Spotify list to accompany the feature

And what costume shall the poor girl wear

To all tomorrow’s parties?

A hand-me-down dress from who knows where

To all tomorrow’s parties

Some thirty years ago one pop band’s trajectory (which had begun several years earlier in the drab London suburb of Catford) ended, to the surprise of the listening public, on a hard-earned artistic masterstroke achieved while fractiously splitting under the strain of internal tensions. Meanwhile, another band had just exploded into the public consciousness having germinated in the nightclub scene of Birmingham. It seemed they were swiftly and hugely rewarded for what many suspiciously regarded as hollow opportunism. Convenient as it may be to categorise and define our saturated pop culture by the decade, as transitional moments go the demise of Japan and the rise of Duran Duran, for better or for worse as the 1980s got underway, makes for an interesting study.

Many bands born of punk’s seismic cultural moment and given impetus by its energy resisted its growing tendency, after the initial wildly liberating iconoclastic spasm, to limit the stylistic and imaginative palate. To point it out now bears the ring of cliché but for all the Year Zero fervour an evolutionary continuum from David Bowie and Roxy Music was clear. Themselves intermediaries between eras, the key to their ‘glam’ legacy lay in the legitimisation of the links, already implicit in the style-obsessed beat boom and psychedelia, between pop music and the fine art/fashion/design nexus. They patented notions of bands as a total production, of pop stars as created personae, and provided a witty riposte to the stagnant idea of virtuoso ‘rock’ as pop music’s authentic mode. They suggested, after Warhol, that anyone armed with an idea could create themselves anew, with something of cultural interest and value as the byproduct – an attitude central to punk’s own empowering ideals. Mainstream pop critics love a two horse race, and the one dominating the 70s saw Bryan Ferry and Bowie supposedly duke it out for credibility. An eloping Eno arguably helped the latter prevail, co-piloting the pop ‘chameleon’ towards an existentialist profundity on Low. Dubbing their Berlin partnership the New School of Pretension, the European art school cover shots for “Heroes” and Iggy Pop’s The Idiot say it all [referring as they do to paintings by Egon Schiele and Erich Heckel]. Ferry’s rather singular, increasingly lugubrious refinement of glamour for its own sake, on the other hand, would come to be judged increasingly one-dimensional.

Japan’s snarling first incarnation, barely recognisable from the mature aesthetes they later became, was founded in the heat of punk. It was this scene which had reduced glam rock’s excesses to its base constituents but was itself splintering under the pressure of the three minute thrash/trash constraints into the fascinating kaleidoscope that would, eventually, be dubbed post punk. A year before Japan’s first release Ultravox! had debuted under Eno’s glamfather tutelage, with John Foxx claiming he wanted “to be a machine”, his band duly intimating their compliance as the album closed out on the febrile, dystopic electronics of eerie cyber ballad ‘My Sex’. Howard Devoto had quickly strayed from Buzzcocks toward the more esoteric ambiances of Magazine, and Wire’s testing of punk’s minimalism to breaking point gave way, here and there, to atmospheric, synthetically textured tracks such as ‘French Film Blurred’.

Dismissed initially as glam throwbacks, this arty atmosphere allowed Japan to gradually emerge from the shadow of critical derision. Incongruity, in any case, was virtually a raison d’être for the band with their charismatic but curiously wary and vulnerable frontman David Sylvian (après Sylvain Sylvain, née Batt) explaining the band’s name as being motivated by a desire, simply, to be as radically different from the milieu in which they had grown up as possible. They dabbled awkwardly during their early phase with reggae and funk, throwing outré shapes – a Germanic march here, a touch of cabaret there – all to incoherent, sometimes bizarre, occasionally compelling effect.

Typical early single ‘Adolescent Sex’ (1978) commenced as something of a nu glam dirge, but a wash of bright synth in its first middle eight signalled a band striving to sound different, modern – unique.

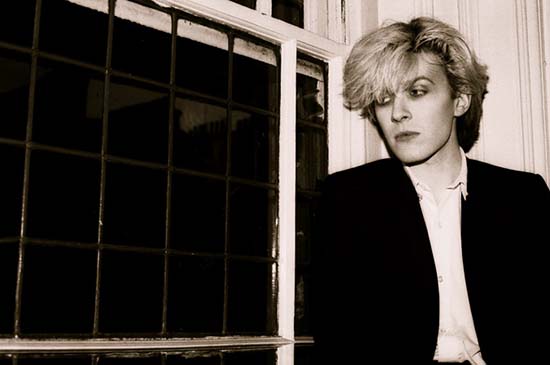

Emboldened by Bowie and Eno’s arch posing but still drenched in Roxyesque glamour, Japan’s sound and image began to alchemise into a remarkably complete aesthetic that seemed to draw on the exotic, foreign and unknown to provide the rhythms and textures in which to couch Sylvian’s oblique musings. Steering clear of an emerging synth pop’s futurist excesses, the sparse yet sinuous sound of 1979’s Quiet Life was perfected the following year on its seamless follow up, Gentlemen Take Polaroids. (That album’s velvet rich production seemed to be acknowledged by their own progenitors when Roxy bowed out on 1982’s densely luxurious Avalon).

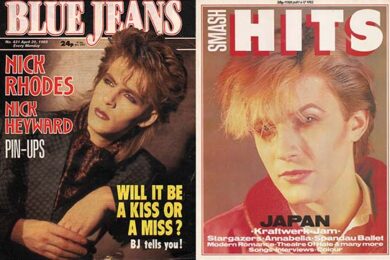

Delivered from behind Sylvian’s kabuki-like mask of coiffeur and pan stick, every other lyric was suffused with melancholic images of “drifting far from shore” in “slow boats”, as from “every port of call comes a time to go”. Sharing the post punk (post Low, post Ferry) vogue for alienation and ennui, they provided a beatifically languid counterpoint to the taut, grey anxiety of Joy Division. By the time of Tin Drum (1981) Japan had refined and driven their blend of abstract rhythm and ambience towards a stark, angular sonic plain.

Stunningly innovative interplay between Steve Jansen (Sylvian’s rhythmatist brother) and Mick Karn’s fretless bass allowed for a Sino-Japanese emphasis on the spaces between sounds. The resulting music displayed every bit as radical an absorption of ‘other’ sounding musical culture by a Western pop/rock muse as was attributed to various contemporaries such as Talking Heads and Malcolm McLaren, and ahead of examples set in the mainstream pantheon by Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon. Crucially they managed to transcend all of their obvious influences to replace them with something that didn’t quite sound like anything that had gone before.

A smattering of geopolitical allusions (from imperialist China to a divided Berlin; all somewhat Bowie-derived) gave the impression of the artistes rather high-mindedly framing personal neuroses in the world’s real politik. All the brooding angst over the need for transformative escape from some nameless oppression mirrored nothing, however, so much as the aspiration of pop careerists wishing to escape an otherwise unremarkable life, thus becoming conduit to the vicarious desire of that voiceless legion which does not or cannot become pop stars, but still wants and needs to dream: the fans. The highly sculpted image with which they presented their enigmatic work was perhaps the main element that eventually saw them turn unwitting midwife to an entire scene with the emergence of the New Romantics – and the predominance of a ‘new’ pop sensibility that Billy Bragg, with some due piety, referred to as “all style over content”.

Baby Jane’s in Acapulco, we are flying down to Rio

Reviewing Only After Dark (2006) Time Out’s John Lewis noted dryly the absence of Sylvian and co from the track listing. It was a retrospective compilation by Duran Duran’s founding members Nick Rhodes and John Taylor (née Nick Bates and Nigel Taylor – self-reinvention, once again, at pop’s spinning deed poll) which celebrated the strange fascination of an alternative 70s music scene that spawned them. The implication from Lewis was that perhaps some influences were a little too close for comfort. In fact, as they rehearsed in Birmingham’s fabled Rum Runner, a nightclub overseen by their entrepreneur managers Paul and Michael Berrow, the nascent Duran were absorbing creative DNA from a veritable cornucopia of glam, post punk, new wave and synth pop, much of it spun by Rhodes as a resident DJ (the provincial counterpart to Rusty Egan at Billy’s) – but there’s little doubt that Japan were a seminal and relatively contemporary chromosome. When Rhodes later had a book of treated polaroids published it became hard to shake the impression that he could scarcely have been more in hock to this particular inspirational predecessor. Suffice to say the art school baton was being passed once again – though surprisingly John Taylor was the only member of either band to actually attend one.

Rather like Tony Wilson in Manchester, the Berrows had turned away from London and looked West for inspiration. Loosely modelling their club on Studio 54, they’d return from sorties to New York with funk, disco and more abstract electronic dance music by the likes of Gino Soccio purchased, seeking a band that might bridge the gap between UK pop/rock and US disco/funk. Speaking of disco, a key step change for Japan had been the incorporation of Giorgio Moroder’s spiralling propellor-like sequencers and synths. These had entranced Brian Eno on hearing Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ into declaring: “I have heard the sound of the future."

Having already used this arpeggiated synthesizer effect on ‘Quiet Life’, Japan collaborated directly with Moroder on the single ‘Life In Tokyo’ (1979, and notably replete with an extended 12” mix) in a calculated bid to bring art rock to the (disco) dance floor. Though Sylvian’s diffidence would steer his band from the discothèque door, Nick Rhodes applied similar sequencers on four out of the nine tracks that made up Duran Duran’s eponymous 1981 debut – including first single ‘Planet Earth’ – to seal that bid. Those paying close attention would also have noticed a percussive lift from ‘Tokyo’ meshing with the camera shutter that fires off ‘Girls On Film’. With spirited naïveté, and ignorant of the re-edit and beat stretching techniques pioneered in US clubs, producer Colin Thurston and Duran set about recording extended ‘night versions’ of their early singles in their entirety, from scratch. Drummer Roger Taylor’s powers of concentration were sorely tested – they really don’t make ‘em like that any more.

Rhodes’ love affair with sequencers continued on to the follow up album widely regarded as Duran’s definitive moment, Rio (1982), where the patterns took on an opulent twinkle reflecting a decisive departure towards a warmer, melodic chart friendly pop. A synth obsessive, he shared Japan’s keyboardist Richard Barbieri’s predilection for sparingly deployed, quirky sonic minutiae to create new and abstract sounding textures. This tendency lent ‘Save A Prayer’ (in whose mystic indulgence lay the colour reverse to the despairing negative of ‘Ghosts’) its exotic plangency, and was given free reign on ‘The Chauffeur’, a studio production tour de force whose glinting enigma and Helmut Newton inspired video drew on a strikingly similar set of references to Japan’s ‘Nightporter’. In a similar dynamic to Japan, Rhodes’ electronics blended with the commercially astute and individually innovative disco/ funk/ rock hybrid of the Taylor triumvirate and Simon Le Bon’s zesty turn of phrase and melody to create a musically ideal pop hybrid for its moment.

Technology during the 70s had infiltrated and reinvigorated conventional ideas of the pop/ rock group with a quotient modernity, something both bands had grasped in their desire to challenge and continue that lineage. In fact it’s hard to resist seeing a symptomatic parallel in the first casualty of either band being lead guitarists Rob Dean and Andy Taylor – was the most traditionally ‘rockist’ element, willingly or otherwise, the most expendable? Mick Karn, who contributed wind as well as his hallmark – nay benchmark – fluid bass to Japan’s sound, was rumoured to have been open to a collaboration with Duran before his sad early death from cancer in 2011. He was the bona fide instrumental pioneer Duran could never quite claim in their ranks; the flamboyant and playful yin to Sylvian’s solipsistic yang, he might well have been spared the frustrations he encountered in Japan had he somehow been born a Duranie instead.

As Duran’s original lead singer Stephen Duffy comments, “It was exciting because we started the band at a point before music started repeating itself… since then music has become more or less derivative. But with things like Kraftwerk and Bowie’s Low… you just thought it was going to go more and more futuristic." Rhodes averred in 1982: “Things were getting very stagnant in England, when the punk thing died out just after the Sex Pistols split up… it was about time people stopped reviving things – there was a rockabilly revival, a mod revival… when some new band like us came out it was like a breath of fresh air to a certain extent.” That neophyte spirit seemed gradually to drain from UK pop in the decades to come; having weathered the relentless retro of the Britpop 90s he’d perhaps be wise to keep his counsel now as Duran’s own era of ascent is, predictably enough, subject to revival.

Sweetheart I’m tellin’ you, here comes the zoo

“Duran Duran dressed like Japan… then they went off and made a sensible commercial hit record” rued Japan’s manager, one Simon Napier-Bell. “Japan could not do that. They played their own esoteric music. But it gelled on Tin Drum. And when it gels it sells!” Eschewing the overt introspection that hung over even the more glamorous corners of the post punk zeitgeist, but retaining enough of its darkness for shading, Duran built on ground won in the wake of Gary Numan and Adam Ant’s return to unabashed, Bolanesque idol-making – and yes, you could almost smell the gel.

The shaping presence of urbane, more middle class management marks another similarity between the bands – but also a significant difference. A predilection for fashion, make up and the conscious integration of image and music came as naturally to Duran as it did to Japan. Their precocity stood in contrast with Sylvian’s talk of image being “a mask to hide behind” however. The briefest glance at the live film As The Lights Go Down (1984) shows Duran doing for euphoria what Japan’s show Oil On Canvas (1983) did for stately ambience. Poised restraint was transmuted into an outburst of energy that spoke directly to the exuberant yearning of youth.

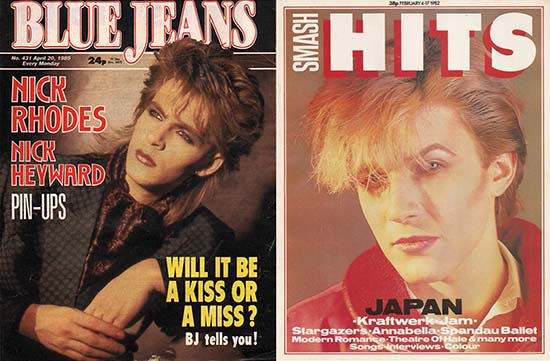

The ensuing teenage hysteria – something they often claim (perhaps a little disingenuously) not to have anticipated – gave rise to an enduring perception of Duran as some sort of missing link between The Bay City Rollers and Take That. It was the ruthless pursuit of commercial success that aroused the suspicion of cynical ‘marketing’. They did jump with a splash into the brio and gloss of the pop mag boom, moreover granting shoots to Jackie et al in the hope of ramping up brand recognition and sales – credibility be damned. Nonetheless, with a powerful live show that amped up their self-conceived pop and would go on to fill stadia across the globe, their integrity as a band was by no means a negligible aspect of their rise to popularity. It would be nearer the truth to posit them as a bridge between the flamboyant spontaneity of glam and a certain studied style (Franz Ferdinand, The Killers, The Strokes) prevalent for the last decade or so. The aesthetic of the current relentless boy band treadmill – by turns grinning, sentimental, melismatic – owes far more to the comfortingly retro soul pop virtuosity of Wham! or Culture Club. Duran’s often abstract art pop was always less housewife’s choice than a baroque, romantic escape from the heartache in every dream home (or housing estate, or classroom, or dead end job).

The machinations of an Epstein or Loog Oldham were one thing; the arrival of a Ziggy Stardust another. In the new decade’s media environment a tipping point was nearing where record companies second guessing the market appeal of their signings would become second nature. This prompted the rise of an army of ‘stylists’ and what had seemed like a radical creative strategy in the 70s gradually became a music industry contrivance. Sylvian hinted in interviews at tensions between Japan’s artistic vision and their often lurid presentation under Napier-Bell’s hit hungry guidance. In one last ditch campaign the manager thrust the role of “most beautiful man in the world” on Japan’s resentful frontman – but the face of an era was self-consciously resisting the era of The Face.

Accounting for Japan’s disintegration in terms of “the valuable content of both lyrics and music (being) buried beneath… too much imagery” Sylvian complained that “people tend to stop at the image either of the band or of the music – they don’t tend to look any deeper because it’s enough for them”. His growing ascetism had its disciples. Talk Talk – Duran’s labelmates and one-time support act – would follow Sylvian’s lead into more jazz-tinged contemplative mode, crafting music that would lead Rob Young to cite both in his book Electric Eden as purveyors of ‘visionary’ English music; a retreating Stephen Duffy would seek pastoral escape from me-decade excess with The Lilac Time.

Napier-Bell, meanwhile, could but envy Duran’s ready collaboration with their custodians’ stellar ambitions. “I had never met people with such ambition before…” Duffy nervously remembers. John Taylor recalls: "It wasn’t just sitting and dreaming, it was Hammersmith in 82, Wembley by 83, Madison Square Garden by 84." When, remarkably, this game plan reached its heady zenith in reality the album they were promoting even included the Berrows in its overblown title: Seven & The Ragged Tiger, a septet of band members and managers grappling, as Le Bon put it, with a “a symbol for luck, chance, success”. Teaming up with promo director du jour Russell Mulcahy, the Berrows had flown the band to exotic locations (Sri Lanka, Antigua etc) to shoot clips so cinematic they were able to sell little English nuggets of Hollywoodised imagination back to a mainstream America who, excitably fixated as ever on the dream of success through sheer ambition, believed a second British Invasion was on. “Video to us is like stereo was to Pink Floyd” Rhodes exuded grandiosely to Rolling Stone, and it became routine for the press to link Duran’s staggering US success to the fortuitous arrival of MTV.

The team’s luck was rooted not so much in foreseeing the explosion of video as viral marketing tool however as much as their single-minded targeting of the majors, eventually signing with the then world bestriding EMI. This would allow the economic opportunity to entrance and allure adolescents and adults alike with a sophisticated confection of sex, humour and style – hardly surprising they’d soon peak with a Bond theme. By the middle of the decade they had seemingly mirrored its arriviste spirit: this wasn’t panto, it seemed to offer an actual lifestyle. With a string of shiny, confident and increasingly brash trans-Atlantic hits, Duran Duran flashed a light (as the cliché goes) off chrome in exclusive nightclubs and palm-fronded, surf-lapped beaches in unknown exotic climes, back out into the ordinary world of the pop loving populace. Therein lay the rub: for a serious American and European rock press that had learned too much from punk to be fooled again, it was too late for all that. Lennon’s wide-eyed goal of the “toppermost of the poppermost” had apparently lost its innocence. Political credibility was something Japan had never particularly had to contend with, but Duran’s conspicuous commercial success guaranteed that the more they shrugged it off the more they would be defined through its prism.

Of deep meaning philosophies where only showbiz loses

The roots of the long-standing rivalry between Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet at the garish heights of 80s chart dominance actually belie their glitzy arrogance. Both were post punk groups who emerged from contemporary club scenes that were the latest blueprint for a continually evolving notion of clubland as an imaginary escapist zone liberated from social norms. Music, style and erotic deviation – plus a few optional drugs – were the currency in the dry iced demi-mondes of Iggy’s (or Grace’s) ‘Nightclubbing’ and Siouxsie’s ‘Happy House’, thronged with the political swingers of Bowie’s ‘Fashion’. Of course, when it came to The Blitz in its famously extravagant pomp, you had to make an effort to get in first and Steve Strange’s notorious door policy drew charges of elitism, but Gary Kemp recalls a deliberate absence of distinction between the bands onstage and the audience.

Spandau’s early cod imperialism saw them lose credibility never quite regained from the sensibility – taste by any other name – that the Rum Runner’s reputedly warmer provincial vibe fostered in its house band. A London thing perhaps, but the point remains that prior to the era of expensively bland wine bars, designer wear and rare groove (thankfully obliterated by acid house and that great leveller ecstasy) punk’s ideal of DIY inclusivity was upheld. The motto could easily have been Ziggy’s shamanic exhortation to “gimme your hands ‘cos you’re wonderful”. The New Romantics fused the sweaty rush of disco and punk with the arch froideur of Europhile art school pretension to become the profound manifestation of what Michael Bracewell calls "the paradoxical proposition of an exclusivity that was open to all”.

At the end of 1984 Duran walked off from Spandau with the final scoreline of Pop Quiz, but they’d already clinched first prize for Thatcherite hubris earlier that year when a naively posturing Nick Rhodes tried on a bit of band philosophy at a US press conference. “We have a very positive thought of our own… you should move forward instead of being taken by all the gloom… we’re just saying we’re about entertainment… sort of private enterprise… doing something for yourself instead of being pulled down by everybody else.” This handed the knife to those all too ready to associate them with the distasteful rise of the yuppie. More accurately they represented a music industry paradigm of that small ‘c’ conservative ethic which says work hard and reap the rewards. Hardly the first (or last) band in history to sneak models, champagne and cocaine onto the rider, the hedonism that had once been a target of punk’s cut price speedy rage was now conflated with the malign notion of a heartless ‘politics of envy’. Always the most ‘punk’ in spirit, John Taylor’s sensitivity on how Duran were perceived probably contributed to his spiral into drug and alcohol dependency; in the context of pioneering art pop up to arena-packing level the closest he’d get to rebellion was saying he preferred Pepsi at a junket for tour sponsors Coca-Cola. Rhodes’ preferred strategy was to play up to the role. Knowingly casting himself as a Liz Taylor-esque soap bitch (he even briefly resembled her in his Arcadian phase) he closed out a 1997 BBC documentary on Duran thus: “The Life and Times of Duranasty. [smirk] Yes."

The consumer bomb detonated by the global success of the Beatles exploded as the horror and austerity of war receded. Punk’s aftershock followed barely more than a decade later, the first time a revolutionary attempt was made to take stock and question the values, morality and social impact of the monumental industry that pop music had become. Ideological conformity, of course, breeds rebellion and the wave of 80s ‘new’ pop aimed to entertain and delight unfettered by intellectualism – and unafraid to demand commercial recognition for the effort. Pop, in other words, that lived up to its implicit meaning: desire. Colin Newman recently remarked that “Duran Duran were Wire with nice looking boys and nice cheerful tunes… people talk about the early 80s as being this amazing post punk thing… most of ‘em didn’t even know about that stuff, what they knew about was pop. Pop suddenly supplanted everything.” Because that’s what pop does.

Scritti Politti’s Green Gartside has remarked that “the unexamined pop life wasn’t worth living”; in punk’s wake his and other self-reflexive projects such as Dexy’s Midnight Runners, Heaven 17’s British Electric Foundation and Public Image Ltd attempted to use style and pretension to infiltrate and subvert the business – i.e. music’s corporatisation – from within, publishing manifestos, launching labels, forming ‘companies’ and pastiche branding their product. All the faux autonomy and ironic business suits were, however, only so much fancy dress, bankrolled as they were by the woolly-sweatered likes of Richard Branson. It was wry to note that whilst, plus ça change, card-carrying Red Wedge members of yore H17 funded their recent comeback doing an ad for a community-based Yorkshire broadband company, across the luxury gap Duran settled for Dior. And Swarowski. Perhaps Fad Gadget, an act at the left of the synth pop spectrum, was right to ask on ‘Luxury’: “Can a man ever have too much?” One consistent liberal credential running through post punk and on into new pop was an empathy and identification with black music’s struggle and celebration, exemplified by BEF’s reimagination of Steel City Sheffield as a cousin to Motor City Detroit. Duran’s road to pop Babylon involved at least one radical pitstop in this respect with Nile Rodgers recalling Capitol executives rejection of his electro-stutter remix of ‘The Reflex’ on the grounds that it sounded “too black”. The band stood by the mix and the record became a worldwide, era-defining smash (and one of the stranger number one records in living memory) striking a blow against a racist corporate hegemony – by accident as much as by design. (Whether it excuses their later cover of ‘911 Is A Joke’ is, of course, debatable…)

John Taylor was often quoted as wanting Duran to fuse Sex Pistols with Chic; most could see the parallel with the latter’s svelte, sophisticated disco pop, but were baffled when looking for evidence of the former’s confrontational nihilism. The Clash seemed more apposite: ‘radical-chic’ poseurs with a less equivocal embrace of dub, funk and disco (as compared with PiL’s morbid abstraction of the same) who furthermore ‘sold out’ and went stadium rock in signing to CBS. Nonetheless, if the hoped-for fusion was never borne out musically (Taylor would go on to collaborate with Steve Jones) Duran’s emergence from punk and subsequent espousal of disco is revealing. Punk’s narrative was (and continues to be) rife with talk of rising up from the (sub)urban doldrums, escaping and getting ahead – on your own terms. With the manifestly upwardly mobile Chic the same agenda was self-evident, however differently expressed. Following disco, the rise (and rise) of hip-hop as the globally dominant black musical form has often been considered analogous to punk – not just for its anger but also, crucially, its aspiration.

With equality of gender and sexual orientation amongst punk’s other progressive gains, Rhodes quipped that, “Duran Duran are a band for girls, boys and everything in between." Pleasure was the unifying principle – but it was dystopian, like warm leatherette. ‘Girls On Film’ saw them inherit the accusations of sexism from Roxy’s ‘covergirl’ tradition – yet it tends to provoke catwalk struts and vogueing on the dancefloor. Its once notorious video (directed by art pop alumni Godley & Creme and intended for giant banks of screens in nightclubs) may seem on reflection to be almost a gateway to today’s hypersexual voyeurism, particularly hip-hop’s blend of five-carat misogyny (the kind memorably lampooned in Chris Cunningham’s clip for Aphex Twin’s ‘Windowlicker’). Nevertheless, as much as it revelled in the glamorous sexual frisson never entirely absent from pop, the lyric’s implied erotic violence tempered that thrill with a perspective on its commodification.

One thing was for certain – Duran Duran would be marked out for nothing so relentlessly as they were for sensual gratification and materialism. In an ever more morally complex pop culture perhaps it all begins to make some strange kind of sense. Take Kelis, an empowered sex kitten with claws (who recently recorded and performed with Duran): no matter what she would go on to achieve she kicked off her career paying tithe to her "pimp" Ol’ Dirty Bastard. “In exploitation’s name” as Le Bon once mused on pop as a marketplace, “we must be working for the skin trade."

When two tribes go to war a point is all that you can score

“You poor little cows who buy Duran Duran records, you need serious help ‘cos those people are conning you” railed John Lydon. “Making records for people just because you think that’s what they want – to me that’s fascism.” As with much of punk’s seditionary rhetoric its lordly avatar’s fulminations foundered on the rock of absurdly finite logic: as brilliant a contrivance as Metal Box could hardly have been recorded and packaged in the belief that no one wanted it. It was ‘indie’, of course, that would emerge as the most enduring vestige of punk’s idealism and it was against this ultimately numinous concept that any group perceived as a ‘style band’, let alone one signed to a major, would come to be most severely tested. Growing out of the left-leaning, essentially Marxist side of punk that hoped to guide youth culture beyond the zero sum game of cash-from-chaos anarchy, a scene developed that was dressed-down and thrifty, anti-materialistic and non-commercial by nature. Sadly, more often than not, altruism succumbed to the pressures of survival, many labels serving as subsidiary clearing houses for the big companies.

Scritti Politti’s Camden bedsit squatters had helped pioneer (along with the Buzzcocks of ‘Spiral Scratch’ and countless others) the very idea of independent production and distribution. Green’s bold journey from the haven of ‘indie’ obscurity on Rough Trade into the shark-infested waters of global success with Virgin was considered a key moment, and would eventually prove, by his own account, to be mentally debilitating. Morrissey, whose dramatis personae of cringing loners would become the most visible antithesis to new pop’s brazen dazzle, envied the move. His foil Johnny Marr, arguably keeper of The Smiths’ true flame, downed tools on the verge of signing with EMI on the grounds that having become bigger than their own heroes Roxy Music and T Rex they should probably leave it at that. “They did have a series of hit records” recalls Geoff Travis of his flagship band, “but I think they just felt they should have more. And I mean that’s understandable, but irrational… [they] weren’t making anodyne, pretty pop records for 14-year-old girls therefore they’re not gonna sell as many records as Duran Duran, it’s just a fact of life. You have to get used to that Morrissey”.

That the mild mannered Travis should express such apparent contempt for teenage girls – and presumably actually meaning the mass pop market, which included plenty of boys and possibly even some grown ups – says much for the strength of ideological conflict played out in the 80s pop scene. It was an attitude that fostered a paradox – by deliberately appealing to a constituency that defined itself outside an elite-driven mainstream, alternative or ‘indie’ rock became the very epitome of elitism.

Whilst an undeniable plethora of stunning innovation flourished from the condition of ‘independence’ (Orange Juice, Cocteau Twins, My Bloody Valentine, The Smiths themselves… the list is endless), a sanctimonious assumption of ‘indie’ as the very kite-mark of righteousness began to take hold amongst a tribal and seemingly rather white bread demographic, something Green refers to with typically intellectual precision as “the reification of indie”. It was a tenuous creed that would soon unravel: how to set rational limits on pop’s innate drive to succeed remained ambiguous.

“We want to be the band to dance to when the bomb drops” went an early Duran sound bite, but by the middle of the decade you could have been forgiven for thinking they might seek profit from Armageddon itself. Zang Tuum Tumb didn’t dally with the vagaries of ‘indie’: coming right out of the traps as an imprint of Island Records, the label’s success with the outlandish and outrageously artificial marketing bonanza of Frankie Goes To Hollywood torpedoed the glossy complacency Duran typified. Seizing the initiative in deliberately and radically combining overt political provocation with crass commercialism, it also marked the moment when style and artifice turned from post-modern ruse into knowing irony. An ideological coup that came at a human cost, the band were fed through Trevor Horn’s Fairlight compressor to emerge embittered puppets in new pop ‘theorist’ Paul Morley’s cunningly staged media manipulation play. (The mise-en-scène was curiously reminiscent of punk’s denouement in the feud of Johnny and Malcolm). In reaction to the Frankie phenomenon, and a measure of the tone taken in various inky columns at the time, Simon Frith wrote of “the neurosis of a society told, amid the wastelands of dead factories and eked out social security that the solution to our problems is to have fun”. The very idea of pop success, and the mindlessly complicit hype-believing record-buying public on which it is supposedly predicated, was being at once satirised (by ZTT) and criticised (by the cognoscenti) as the suspected enemy within.

Little doubt that they played their part in the false plastic dawn of the 80s, but as Simon Le Bon recently demurred, "People talk a lot about Duran Duran and a decadent lifestyle, a hedonistic thing, and that’s not right. That’s not what we were selling… we were presenting optimism – and that’s what people were attracted to." In what is perhaps a crowning irony it takes Bob Geldof, high priest of self-eviscerating 80s pop philanthropy, to point out that as the consumerist boom and the rise of celebrity culture smoothly moved up another gear “what (Duran) were showing to Britain – very cleverly in my view – was this newer world”. With the passing of time Rough Trade’s fragile utopia was torn asunder by its inability to reconcile the contradictory forces of maverick freedom and economic reality; a little later the story of Creation concluded in the blizzard of neo-Roman decadence brought about by the phenomenal success of Oasis. The 1990s lad/ette rallying cries of “let’s ‘ave it” and “livin’ the dream” sounded every bit as acquisitive as the preceding decade’s mainstream excess, by which point, frankly, the urge arose to reach – á la Quentin Crisp – impatiently for one’s trilby with the admonition that decadent celebration is all well and good but really, boys and girls, what about the presentation…

“9 a.m. the beach, tequila mayhem/ The sum of all suburban daydreams” sang Le Bon on ‘Mediterranea’ (from 2011’s creditable Mark Ronson-produced Duranalogue All You Need Is Now) harking back to the ‘exotic video’ phase for which they would spend the rest of their careers apologising. Every bit a tender paean to the massed Balearic pilgrims that ‘indie’ anthem ‘Girls And Boys’ was scabrous caricature, the notion conveyed was that however unattainably affluent their fantasies might have been, they were only ever to be shared in the imagination of their audience – one thing you couldn’t accuse Duran Duran of was hypocrisy.

The whiff of pseudish condescension could linger poisonously over pop’s great socio-allegorical debate. For all that times were hard and hard times are back again, it can get to the point where you might as well say “We don’t want any more people from Sheffield flying away on cheap holidays” – and they might not care for sand but trying telling that to the Arctic Monkeys.

Where are we now?

The artistic cross-pollination exemplified by Bowie and Roxy has helped give rise to a generation that defines and empowers itself by its cultural and consumer choices. In today’s reality, esteemed members of the arts community can be heard citing their contribution to British economic life when making the case on Radio 4 against government cuts to arts funding (…which kind of makes you want to ask if they realise they were faking it, baby?) Dame David and Lord Biryani Ferrari, as they were variously dubbed in inkies and glossies alike, have often been critically distrusted as superficial and shallow, mere actors – sometimes by their own admission. But the constellated work of pop’s conscious stylists could catch, reflect and even influence far more of a changing society, however beautiful, however trite, than some of their allegedly more authentic peers. As much as pop music serves as a compelling metaphor and index of our times, its most important function is to provide us with timeless transcendence from them; they skilfully encompassed both aspects, mirroring the zeitgeist whilst creating memorable, beloved music with their song craft. And this was everything Japan and Duran aspired to.

In some ways artifice was the point, to question what was real about pop, what was valid in modernity. Liberated after the 60s from social constraint artists were free to roam the post-industrial jungle and express themselves through the plastic, the synthetic, the technological bounty that increasingly characterised the physical and cultural life of the so-called Western world. The quixotic relationship between human desire and an ever more ubiquitous materiality was as wittily expressed through Roxy’s ‘Ladytron’ as it would be decades later in the fetishised fembot of Duran’s ‘Electric Barbarella’ (1997, and appropriately enough, as Nick Rhodes loves to boast, the first-ever single to be released exclusively for digital download/purchase). Japan took Bowie’s lead towards a more spiritual quest, diverting technology and style towards an expression of something less material, more profound. Humour, of course, was forfeited.

Michael Bracewell, in his recent cultural analysis of Roxy: The Band That Invented An Era, describes a young, working-class Bryan Ferry being “drawn to the transformative magic commanded by glamour” predicating the band’s popularity on their dissemination of “style as the agent of social mobility”. Glam itself seems to have considerable resonance as a turning point in the long view currently taking hold that the gradual decline of industrial manufacturing in Britain during the late-Twentieth Century has prompted an identity shift towards being a nation of entertainment and service providers. The idea was poignantly encapsulated by visual artist Jeremy Deller in his recent exhibition Joy In People which displayed a photograph of 70s wrestler Adrian Street stood, attired for all the world like a fully paid up member of the Sweet, next to his soot-faced coal-mining father at a South Wales pit-head. What price a snap of the Batt brothers David Sylvian and Steve Jansen flanking their old man in his overalls outside the Catford branch of Rentokil?

A likely element of Roxy’s near-mythic Bryan/Brian rift was the former’s gradual blurring of an imagined vie deluxe with a cologne-drenched narcissistic reality. Ferry’s recent honouring as a CBE seemed more like the correction of an oversight, so long has he been embedded in the rolling acres of the landed gentry. Further down the socio-cultural food chain Duran, who Rhodes, sly to a fault, describes as an “aristocratic band with a working class work ethic” were Lady Di’s faves – natch. By telling contrast David Bowie declined offers of both a knighthood and CBE (“I seriously don’t know what it’s for – it’s not what I spent my life working for”) thus aligning himself not only with his absent friend John Lennon but also those who might prefer to approach the monarchy with a sponge and a rusty hammer.

Social climbing and class war notwithstanding, Ferry’s estranged collaborator (the Bri with an ‘i’) displayed the same basic tendencies in his theoretical decision to “turn the word ‘pretentious’ into a compliment. The common assumption is that there are ‘real’ people and there are others who are pretending to be something they’re not. There is also an assumption that there’s something morally wrong with pretending. My assumptions about culture as a place where you can take psychological risks without incurring physical penalties make me think that pretending is the most important thing we do”. These days Eno keeps flush helping Coldplay pretend they’re U2, hitching his kudos to a quasi-religious, pseudo-political post Live Aid consciousness closer to populism than pop. It’s almost tempting to believe this might be his anodyne, penitent response to the revolution that never came. Pop music has failed in the age of late capitalism to be the lightning-rod for progressive change it once promised to be. The fear is that it may be just one facet in the rise of an aggregated, global, information-based media whose very raison d’être is to spread connectivity and desire. As the sustainable limits of human consumption loom it might be prudent to ask again what the ‘physical penalties’ for pretending might be, because if you’re going to play the pop game you’ll always end up, as joueur extraordinaire Malcolm McLaren might have put it, with ‘Some Product’. It may well be futile to pretend otherwise.

Maybe it could all boil down to the essential decadence of a mid-Twentieth Century artistic movement whose protagonists simultaneously demonstrated the wanton disposability at the heart of industrialised modernity whilst reaping unimaginable wealth doing so. If Pop Art theory was coined by Bryan Ferry’s onetime tutor Richard Hamilton (“Transient… Expendable… Low cost… Mass produced… Young… Witty… Sexy… Gimmicky… Glamorous… Big Business”) then Andy Warhol’s infamous “business art” aesthetic minted it. Their ideas resonate through pop music like shiny balls in a bagatelle; ironically the inexhaustible stream of pretenders to pop success wish for nothing more than to be indisposable, desperately seeking a lasting place in culture’s ever lengthening memory. The democratic curse of TV talent shows wilfully laying the process bare and the existential threat posed by digital technology seem almost… karmic. The 1980s may have been the last time pop music could, however precariously, balance a spiritedly cynical take on modernity with a celebration of that almost infantile spirit embodied by a T-Rex lyric. Pop today is a well-oiled production line of diamond star halos, be they cut or in the rough – shining bright, untarnished by doubt. David Sylvian seemed to explicitly rescind Pop Art’s values in the almost reactionary purism of the title he chose for Japan’s posthumous swansong, Oil On Canvas.

Is this the way they say the future’s meant to feel?

Seasoned free festival attendee Bowie had his (glorious) lap of honour at Worthy Farm. Having thrown open the paddock gates to American hip hop and r & b aristocracy with both Jay Z and Lady Bey to headline in all their multi-split-screened, sequinned opulence, wouldn’t it be suitable to celebrate the former glories of some home grown provincial British bling? The style and sophistication of Roxy or Duran might seem a little absurd in the context of a muddy field in Somerset, some might say morally incongruous. But as the ashes of pop’s utopian illusions and revolutionary delusion swirl amidst the detritus of mass consumption that blows down the highways of today’s proliferate, profligate festival thoroughfares, a little refined glamour could be just the tonic – “a diamond in the mind” and not just Kate Moss’s Hunters.

To quote Jarvis Cocker, a main stage titan perhaps justly canonised for marrying an obsession with style to an acute social conscience, “it didn’t mean nothing”. Did it?