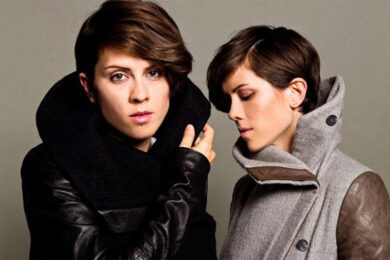

When an indie rock act has been steadily gaining traction over their past few records and decides to change direction and create a slick pop album steered by three different producers, anything can happen. It’s not often that the result is that band’s best work to date and garners mass appeal while still keeping longtime fans interested. But that’s exactly what happened in the case of Canadian duo and twin sisters Tegan and Sara.

On their seventh studio outing, Heartthrob, the Quins prove themselves to be a band committed to evolution. While their earlier music and live shows (going back to a 1999 Lilith Fair stint) maintained a more straightforward singer-songwriter flavour, pop sensibilities have been bleeding into their work for a few albums now. The band’s breakthrough single, ‘Walking With A Ghost’, from 2004’s So Jealous (notably covered by the White Stripes) was the first signpost towards the band’s more recent pop-inflected output, including The Con and Sainthood, both produced by Death Cab For Cutie’s Chris Walla.

But it is more than music that has put the Quins in the spotlight. The openly gay sisters are devoted to using their position responsibly, which can create a media circus, as was the case when Sara Quin penned an open letter to Tyler The Creator, calling him out on the homophobia and misogyny of his lyrics. On another occasion, the band probably received more attention than they had wanted in 2009 when NOFX released a song called ‘Creeping Out Sara’, chock-full of anti-gay sentiment that songwriter Fat Mike claimed was tongue-in-cheek. (Fat Mike’s defense in a Spinner interview contained the memorable quote "We think gay people are awesome and better than straight people because they’re having more fun".)

Though such identity politics can overshadow the media’s focus on the band’s music, the Quins know when to leave the politics out and focus on art. From lead single and album opener ‘Closer’ on, Heartthrob is a deliciously sugary tour-de-force that focuses more on up-tempo songs of love and lust. There is decidedly less angst here than on the band’s earlier work, but that anxiety isn’t missed.

To start by going back into your history, how did you start making music, and how old were you?

Tegan Quin: We were fifteen when we started writing. We’d been playing piano since we were seven, even though we were showing interest in piano, we’d never shown interest in being a band. We were not those kids who were, like ‘I wanna be famous and be in a band! Pay attention to me! I’m going to do backflips and sing for you!’ We were very shy. We were in the school choir, but we were never soloists or anything like that. It was when we became teenagers that we started listening to grunge and the Pacific Northwest Riot Grrrl music and we were going to gigs all the time with our friends. I had this instinct that if they could make music, then I could too. I started composing on the piano, and I had been classically trained for eight years, so I didn’t feel comfortable expressing myself outside of the classical genre. We had this guitar in our house and I started sneaking it into my room and writing, and Sara had the same instinct. We started to explore writing together and recording each other. We let a few friends listen to it, and the response was really positive. We let a few more friends hear it, and before we knew it, we were making cassettes in our radio broadcasting class and selling them in the hallways between classes.

When we graduated high school, we didn’t have any other plans. Our mum had tried to get us to enrol in university, and we were really unsure of ourselves and we didn’t know what path we wanted to take. We came from a lower middle-class family, so university was a serious investment and we felt nervous about committing to it, so we asked our parents if we could take a year and play music instead. They were really resistant at first, but then they came around. Within our first year, we made a record, and we signed a record deal and we were up and running.

I actually saw you open for Rufus Wainwright back in 2001.

TQ: Oh, yeah! What city were you in?

I was at the 9:30 Club in Washington, D. C.

TQ: I remember that show!

I could tell that this was a band that was really going to evolve over the years. That’s been

what’s so exciting to me about your music – the evolution.

TQ: Especially during that era, we made a full band record, but the record label laughed hysterically when we asked if we could bring them on the road with us. They were just, like, ‘No. We signed you because you’re songwriters and you’re going to go on the road and support yourselves’. That was terrifying! So there was this whole evolution where we became performers. We always wanted to be a band, and to be seen as a band and not songwriters. But they forced us to be seen as performers and develop our voices. It was like a second adolescence.

You and Sara trade songwriting duties, and I was wondering how you achieve a coherent sound despite your individual aesthetics.

TQ: Sara and I were talking about this earlier today. There was never any competitiveness and we always enjoyed each other’s view, and we always shared our music with each other before we shared it with anyone else. Each time we sit down to write a new record, there’s some excitement and enthusiasm from each of us about what the other one is going to bring to the table. With Heartthrob, we tried to do a lot more collaboration that we have in the past. For five years now, we’ve written for other artists, ten, twelve different artists. It was a funny thing, like ‘We’ve never done this for our own band. But what if we sat down and wrote for our own band the way we write for other people? What if we imagined writing our songs for someone else but it’s about ourselves?’ And, all of a sudden, it was like all five songs of mine that made it on Heartthrob were songs I collaborated with Sara on. I think it helped make the record more cohesive. I think it gave the record two distinct voices that are working together. It feels like a record where people can really get into all ten songs, and not think ‘Oh, this is more me’. I think in the past Sara and I were two different sides of the same coin. Now it feels really cool to be speaking from the same place.

Can you talk a little bit about Tyler the Creator, and what happened there?

TQ: We’ve been asked that for quite a while. Sara called me one day and said ‘There’s this guy and his record is really offensive, and a certain part of this industry considers him a great new talent. And yet he sings these really awful songs about raping a pregnant woman and bragging about it and says ‘faggot’ like 250 times on the record’. I felt really annoyed that the industry is supporting this record, and there’s another side to the story. She said, ‘I want to write an open letter to the industry and the media and talk about the responsibility that we all have to make sure we’re representing our audience’. And the audience we have is diverse, and we wanted to say, ‘This isn’t cool. If you take offense to it, too bad’. I hadn’t heard the music.

So she wrote this really beautiful letter, and we edited it down to what we thought was reasonable and she posted it, and there was this firestorm. It was amazing how many people reached out – TV producers and major editors for huge magazines. We were just, like, ‘We’re not going to support this’. The world is not going to change if we continue to support certain stereotypes. And now that I know so much about it, I think there’s a lot of artists who explore and push boundaries and are not offensive, and I’m not sure that Tyler the Creator is actually that hateful. I think he was really young and pushing boundaries. There’s a lot of bands that are pushing boundaries, and I say ‘Go for it!’ I do think that there’s a certain responsibility in the media, and that’s what Sara was trying to get across. Just because you work for a magazine doesn’t mean you aren’t responsible for what’s in that magazine. It’s okay to stand up and say ‘I don’t want to work for a guy who’s perpetuating ignorance. Even if he’s not ignorant, he’s supporting this idea to be ignorant’. I thought it was really smart of her to push that boundary.

I’m reading Kristin Hersh’s memoir right now. She’s describing the early years of Throwing Muses, and reporters were essentially asking them why they were women. How do you navigate questions like that?

TQ: This is a hybrid answer to your question. Early on in our career, things like our being gay or our being twins overshadowed our music. Then, for a really long time, it felt like us being women and trying to take a bite out of indie rock was overshadowing our music. And now it’s like the pop production of our music overshadows our music. I read other people’s press, especially male press, and I wonder if they are perceived or have to go through so much explanation about being who they are. I wonder if men just get to talk about being musicians and that’s the end of it, whereas women have to talk about being women or being gay or being a twin or being Canadian or being from this genre or that genre. I wonder, and it’s so interesting because for a period of time we were very vocal about marriage equality and Sara was very vocal about Tyler the Creator, and then NOFX wrote that song ‘Creeping Out Sara’ so the media wanted to talk about that.

There was this interesting period where women from that 90s Riot Grrrl movement reached out to us and gave us a lot of support. It was this really amazing time because we got to have a lot of conversations about what it’s like to be a woman in this industry. What I’ve concluded and decided is that all these conversations have left us – I hope – being the most and educated and informed artists that we can be. Ultimately, our job is to make great music, and I hope that that’s what we’re doing. I hope those other things don’t overshadow that we’re trying to make music that will help you through your most miserable moments and also your most romantic and wonderful moments.

You touched a little bit in your last answer about politics and what issues have been important to you. What other issues have been on your radar?

TQ: Right from the start of our career, we were encouraged by our record label and by people around us to be vocal about who we are. Specifically, initially, it was about being women in indie rock, and then it was about being gay, and then it turned into a conversation about marriage equality and feminism and misogyny in our industry. All of those issues have turned into important causes for us. Specifically right now because of what’s going on in American politics and also in England and France, marriage equality for gay people and trans* people is super important to Sara and I. I hope that we can reconfigure how people see and think about queer people in culture, and that we can help buffer some of the transition period from people thinking we’re so different, when really we’re all the same. Those have been the issues. We try to focus our charity work on those issues.

You did some electronic work with the likes of Tiesto and David Guetta. Did that influence your sound on Heartthrob?

TG: Yeah, to a certain degree. Certainly over the last six years since we started collaborating with dance and pop artists. I think what it did was encourage Sara and I so we didn’t worry that we were limited to one genre. I was always interested in that music. I was recently going back to old interviews and old records and even back in the day when we were supporting records like The Business of Art and If It Was You and especially So Jealous, a lot of people were asking questions like ‘You have keyboards on the album. Do you like 80s music?’ Records like If It Was You and So Jealous really had an 80s influence, and I think that we felt like we had to stay within the indie genre so we weren’t able to express that side of ourselves that much. But growing up in the 80s, Madonna and Kate Bush and David Bowie were huge influences on us. And it’s come full circle and there’s so much 90s and 80s influence on us, we felt like we really needed to let our artistic flair just happen and see where it went, and not hold ourselves back and hold ourselves within a genre.

You worked with three producers for Heartthrob. I was wondering when each producer was brought in and how that worked for you.

TQ: The first producer that was brought in when we were interviewing producers was Greg Kurstin. I called Sara and was like, ‘You’ve gotta meet this guy!’ He was working on the Shins record, but he’s also worked with Kelly Clarkson and Pink and Ke$ha and Lily Allen and Kylie Minogue, and he’s got all this female pop vocalist experience. But he’s also worked with Beck and Bird & The Bee and The Shins and Ladytron and all this amazing stuff. I thought, why on earth have we limited ourselves to someone who’s only worked on indie rock? We should embrace this world. Sara agreed to meet with Greg, and she claims within five minutes she was sold. He talks about music, especially pop music, as something that was a living entity, and it really inspired Sara and I, and it made us feel like we could trust him with our songs.

And then after we committed with Greg, he initially said he could only do four songs. I continued to meet with producers, and the next one I met with was Mike Elizondo, and I found him to be really inspiring as well. He’d worked under Dr. Dre for ten years. He had a lot of pop and hip hop experience under his belt, but he’d also just done a Regina Spektor record and a Mastodon record, so again, similar to Greg, he’d also some really incredible and credible records with indie artists, so I really liked him. Then Greg came back and said he could do eight songs, so we only needed one more producer.

Then the M83 record was blowing up, and people suggested we meet with Justin Meldal-Johnsen and I always loved M83, and I loved the transition from indie rock to much more mainstream, hook-y kind of music. I met with Justin almost on a whim. I expected not to like him. I thought ‘He’ll probably be some sort of hipster, some weird savant that I didn’t understand’. But within two minutes, he was standing on his chair and was, like, ‘I just love your music and I want to make stuff!’ I thought, I really like this guy. I think he’s really weird, and I would love to work with him. After that, it was like, I think we have our team. We’ve got these three really amazing people. And they had all played with Beck. That was this really strange thing they all had in common. We’ve got these three awesome people and they all know each other and they all respect each other; they’re all going to listen to each other’s songs and we’re going to make a cohesive record, and that’s what we did.