John Le Carré’s The Spy Who Came In From The Cold – that chilliest of Cold War espionage novels – centres on the character of Alec Leamas: weary, sombre, cynical, scarred inside and out by the things he has seen and done, yet still possessed of a curious nobility that he neither aspired to, nor much cares for, nor has been able to shake off. Leamas accounts for all human behaviour, good and bad, in drily reductive fashion: "A dog scratches where it itches. Different dogs itch in different places."

In the movie version, Richard Burton inhabited the role of Leamas as if it were his own, old overcoat. His Leamas makes one think he would have been ideal to play Don McCullin. But in this age of the documentary, there is no need to wish him back for that purpose. McCullin, fortunately – this film spells out just how fortunately – is available to account for himself.

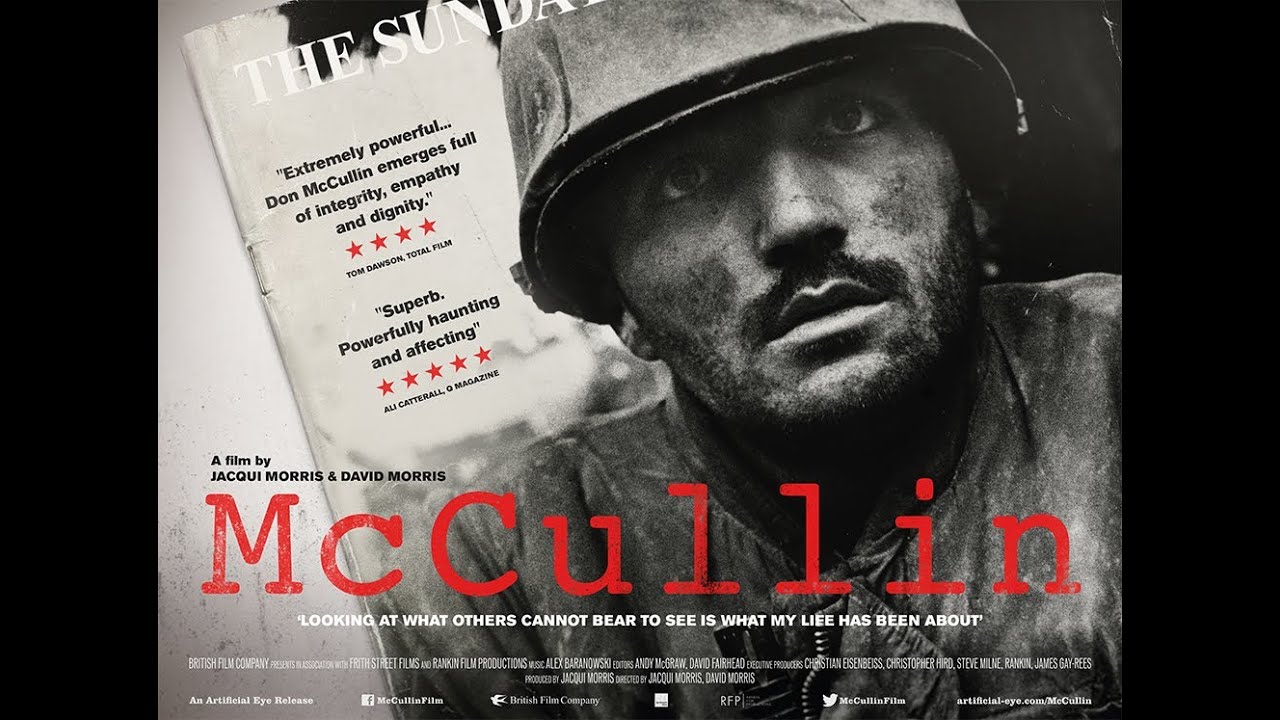

McCullin, the outstanding British photojournalist of the outstanding era of British photojournalism, is described by his onetime editor at The Sunday Times, Harold Evans, as "a conscience with a camera." Which is true; but far from the whole truth, and McCullin himself would evidently not have you accept it as such. Throughout his career, he would have you know, he was scratching where it itches.

McCullin is as much an existential investigation as a biography. Its subject is a serious man of the old school; by which I mean a type given neither to solipsism nor false modesty. Don McCullin does not play down the risks he took; to do so would imply a heroism he does not claim. He was courageous – foolhardy, in retrospect – but he was addicted to action. It was harder for him to stay away than go. He didn’t laugh in the face of danger. There was nothing to laugh at. Just horror unfolding upon horror, to which he was often the only witness of record. He doesn’t understate his opinion of his own work; he knows he was – is – damn good. He cites his own deep integrity, not as a boast, but as a relevant fact. It becomes apparent as the film runs its absorbing course that what he wants to consider, just as it’s what the audience wants to discover, is why he did it. Not why he scratched where it itches – that much is obvious – but why it itched there in the first place.

He speaks – a low, faintly gravelly voice – in the quasi-RP common to a generation of those who Got On from unpromising backgrounds. We hear a faint North London inflection as he recounts tales of his grim Finsbury Park youth. His fellow roughs were his first photographic subjects. He found he possessed a peculiar sensitivity that came out in his pictures. His first war assignment, in Cyprus, honed it, in terrible circumstances. "I was learning a new trade. I was learning about the price of humanity and its suffering." There it is, the impossible alliance at the heart of reportage. One’s trade. Human suffering. From the very start, the key question so often asked of reporters, not least by themselves, was at the front of his mind: "How can you just watch? How can you not help? How can you not act?"

McCullin was made of rugged stuff. He did both; he recorded, and he acted. Throughout his career he crossed the line between observation and participation. In Vietnam, it would become erased altogether. "I became totally mad, free, running around like a tormented animal." The fate perhaps rather patly attributed to Kevin Carter – Pulitzer winner, suicide – was not for him. Does he have nightmares? "Only in the daytime. My darkroom is a haunted place."

There is no self-pity in McCullin, but nor is there an ounce of cant. He suffered too, and will not pretend otherwise. Not as his subjects suffered (although he was wounded, and surely came within a whisker of death as often as any civilian now living), but in passing his life amid atrocities one could not imagine had he not given us pictures of them. He sacrificed the greater part of himself to bring the truth home to our doorsteps – not intentionally, not as a martyr to that truth, but because that’s how it (in hindsight, inevitably) worked out. He wanted to show the worst of the world for what it is, and he wanted to be in it, amidst it, because he couldn’t stand not to be. His impulses were as honorable as one could hope, and as base as one might fear.

McCullin also addresses, as it must, the reasons why even a willing McCullin, or his successors, would now find relatively few outlets for the kind of work he did from the Sixties to the Eighties. The state of mainstream journalism – and of reportage and photojournalism in particular – is not encouraging. But as McCullin might point out, even when it was flourishing, it hardly helped do away with the outrages it showed. It allowed us to know, is all. Many of us would consider that a significant good in itself. But most of us don’t possess the rigorous standards and improbable ambitions that made Don McCullin Don McCullin. He looks back on his career – an extraordinary one by almost any measure – without sentiment, and deems his life’s work futile, as a kind of activism if not as a kind of art.

He now takes pictures of landscapes. As he has said elsewhere: "I am sentencing myself to peace." McCullin shows us a man of preternatural exterior calm, but one seemingly too pensive and unflinching within himself to serve out that particular sentence.