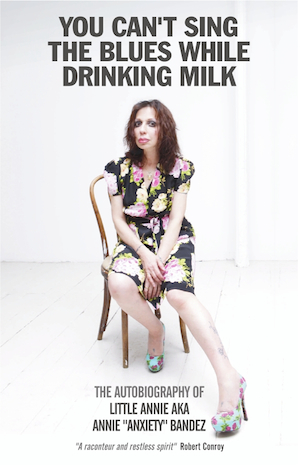

Little Annie, Annie Axiety, Annie Bandez: one life with three names. All are listed on the spine of You Can’t Sing the Blues While Drinking Milk, and the Annies have one incredible story to tell. If you don’t know Annie (or Annie, or Annie), you may know the names of friends and collaborators who open the book with gushing forwards: David Tibet, David J, and Antony Hegarty, who sums up the lady impeccably: “Annie, from Yonkers, Little Annie Anxiety…. A New York baby and a London legend, survivor, impoverished icon… she of dripping truth, curling lip and glistening black eye.”

Annie Bandez still carries the ‘Yonkers honk’ proudly in her voice and also grasps the unsubtle New York sensibilities. She holds back no opinions and holds no shame over her story. Her teenage years would make even Jay-Z’s I-shot-my-cracked-out-brother-over-bling tale look like happy times in the suburbs. Having read the book, it seems a bloody miracle she’s survived. As she mentions in this interview, everyone described in the first half is no longer with us: whether it be disease, drugs or more sinister and more dismal demises in back alleys of New York. By 17 she had been dancing in clubs for years, living on the street, abusing drugs and even took off across the country to LA for a spell. Then one Steve Ignorant came into her life and invited her to England for two months to live in his group Crass’s now-infamous anarchist commune in Essex. Those two months turned into over a decade in Europe and a much lauded, but now much-overlooked music career.

Bandez is extremely aware of the story she wants to tell and purposefully omits ‘distractions’ such as details about her drug addictions and marriages – and she’s had a few of each. In fact, judging by the book, the only significant lover in her life was Italian immigrant Billy, or Guido, who she met when she was a teen and he 29-years-old, and with whom she shared a serious stint of substance abuse, that ultimately took his life. He has much more mention than any husband – she even claims she was a “widow at 16”. Yet even without the majority of gory love and drugs details that so many autobiographies focus on, her life still wipes the floor with fiction.

Even more shocking is the fact she holds a decade worth of life yet to regale us with. The book only documents up to the year 2000, leaving us hanging for Part 2…

What made you want to put it all to paper?

Annie Bandez: Originally the idea came up about 12 years ago, because I was asked by Virgin to do it. But at that time I didn’t really want to – I didn’t think it warranted a story yet. But, basically, I had this really horrendous roommate that I wanted to get away from, so I went back and said yes, so I could move! But once I started, I realised that I really enjoyed the process. More so than a song; it’s problem solving, I got really into the mathematics of it, it was a great learning experience. So having not wanted to do it originally, I’m really glad I did.

Why does it only document up to the year 2000?

AB: Well it was originally supposed to come out in September 2001, but Virgin were going through the process of firing half their staff at the time, then 9/11 happened. They were about to go to print with the cover, which was a problem because I basically looked like one of Bin Laden’s wives, you know, the way I was styled with a veil and everything. I mean, they didn’t say it, but I think it would have sold two copies with that sleeve! So, with all that going on, it just got dropped. But I was really happy; it seemed so inconsequential in the backdrop of what was going on. It felt really inappropriate anyway.

So why didn’t you update it?

AB: I was going to update it but then, for one, it would have been the size of the Bible – the last ten odd years since have been a whole another life again. Also, the past couple of years have been particularly tough, I lost my parents last year, and I don’t know what that means yet. I started to write it and it just started to sound maudlin and self-pitying… Right now I feel I’m too in it to document it.

I noticed that the experiences you had aged 14-17 make up quite a large part of the book. Why did this period of your life warrant so much focus?

AB: I think I went from being – well – I think everyone goes through so much change, but I went from being a good kid, a smart kid, and a relatively happy kid, but you turn overnight into a nightmare; life becomes nightmarish, you become a nightmare to be around, and I just think those years are a rite of passage. It’s a really important time and unfortunately, in that time, just because of the demographics in which I grew up, there was nothing. Literally most kids that I knew ended up getting pregnant and marrying someone from two blocks down the street. I mean, especially if you were female, there was just no future. And I kind of figured that out young. And I didn’t like it. So my rebellion was nuclear.

People reading the book might be a bit shocked at the things your parents let you get away with: travelling the country, living with older men, dancing in clubs. But you speak of them in the book as being very supportive and caring. From your point of view, were they just free-thinkers, or were their methods more ‘of the time’?

AB: My parents realised that they couldn’t push any harder. I got punished like all other kids, but it didn’t stop me. You could not stop me. If you locked the doors I would crawl out the window – literally. I was so desperate to bust out, not away from them, but out of the mould that was being set. And it wasn’t my parent’s parameters, it was the world’s. They realised that the best they could do was harm reduction. They’d say: “at least just let us know where you are.” If they had pushed any harder, I would have just ran. They had talks about making me a ward of the state, but in that case you end up having no control over what happens to your own child. The options were so few at the time. So I don’t think that they were particularly liberal, I just think that they were just very smart.

Can you tell me a bit about your years living with Crass and in Essex? The house they had is looked upon with social significance as this anarchist commune. Did you experience any particular politics or ideals that affected you down the line? In the book it more comes across that you just saw it as a nice place with nice people.

AB: In a sense, the DIY ethic of it stuck with me – but to be honest I couldn’t understand what the hell they were talking about! I really didn’t know that the words meant, it was all so new for me. It’s good to hear that there were political ideologies that went beyond the left and right, and that people were questioning things, but I grew up with that anyway, my parents were both self-educated, working-class. They questioned everything and read everything, so it was kind of in my nature anyway. But on another level I think I was just naïve. Even though they all seemed so worldly and sophisticated to me, because I’d lived on the streets, I felt more protective of them than anything. I thought their beliefs were really great, but I didn’t see how they would work.

In the book, you don’t seem to focus much on your own songwriting or creative process much. You talk of your notepads of poetry, but don’t actually talk about writing the poetry itself. Is that down to you not being particularly introspective or is it because your work flows so naturally that you don’t dwell on the process?

AB: I’ve never thought about it really… it’s just always been something that I just did. It felt so natural that I just never really thought about it. It just had to be done, and I don’t really have the chance to reflect on it. But there’s also that part of me that believes that if I reflect on it too much, I won’t be able to do it. I take a from-the-gut approach to almost everything!

What do you think your story would have looked like told as a modern story in current times?

AB: Well, on a bad day it’s Don Quixote! There’s a bunch of windmills out there and I can either make them into skyscrapers or monsters depending on what mood I’m in. But it’s hard to say, I’ve been blessed in that I don’t think over things too much to where I don’t think they can be done – I’d put that down more to naivety than stupidity or anything. I don’t see the limitations. So maybe that makes it more of a fairytale? I mean, limitations exist and you can come crashing into them, but when I’m starting out with something, I don’t see the limitations, I guess… gosh, it’s a good question. I mean, I’m such a workhorse that it’s never occurred to me not to work. I never analyze things because it would take time out of the work.

Though you don’t focus too much on the business side of your life, you do go into detail about the process of being signed and dropped from your record label. What do you think of the current climate in the business – the vastness of the Internet and that power being seeped away from those major labels?

AB: I think it’s a great thing! It’s WONDERFUL! It couldn’t happen to a nicer bunch of people – they’re like the mafia; I learned that the hard way, as you can see in the book. At first I thought they were all lovely, wonderful folk, which maybe they are when they’re at home. But in business it just doesn’t work like that. I think it’s leveled the playing field. I mean, sometimes you see the other side. That Levi’s ad [a 2007 use of “Strange Love” by Annie and Antony & the Johnsons] got like 60 million hits or something and I know I got paid nowhere near that, but if I’d done it 15 years ago, I’d be a very wealthy woman right now. So on some levels it is totally out of control, but I mean, as artists we were getting robbed all our lives anyway. I’d rather see stuff go to the public for nothing than see some record company idiots rob both the artists and the public. It’s taking out the middleman and I love it.

There is such a huge array of colourful characters in your book, but often seem to pass through quite quickly. If you were to make a cast-list for the book, who would be the top names and why are they the ones who stuck?

AB: Oh goodness, there are so many people who are dear to me, and so many people I’ve lost. It’s been 30-odd years. But there was Billy – his name was Guido – he is still a big part of everything I do; even though he’s been gone for that long, he’s been very much with me. And I think that if he had lived that book would not have been written because I think part of my need to create came out of needing to find a reason to stay on the planet, and keep going things. If he had lived, maybe I wouldn’t have found the need to go on stage or do any of the things I ended up doing, having adventures and all that. My parents, too – even thought I don’t talk about them much in the book because I didn’t want my actions to reflect badly on their lives. But they are so much a part of the way I see the world. A huge impact. But then there was Adrian Sherwood and (his wife) Kishi – a huge mentor of mine; she taught me a work ethic. And CRASS too! These people were a huge part of my life because I was running ragged and they helped me out. So many of my contemporaries and my friends are gone, and it doesn’t make sense to me, it’s illogical. All the people I talk about in the first half of the book are gone, but I really believe they are all still with me in some form.

You Can’t Sing the Blues While Drinking Milk is out now, published by Tin Angel Records

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more