Dressed in black and wearing brothel creepers in London’s Vortex Jazz club cafe, Gee Vaucher’s youthful demeanour and attitude belies the age of someone born just after the end of World War II. It’s testament to living a holistic life and working on her own terms. A life that’s brought international renown as a political artist for Rolling Stone and New York magazines, notoriety as a member of the Neo-Dadaist Fluxus-related performance art group EXIT, then as the Crass collective sleeve and visuals artist. Now the publisher of Exit Stencil Press, Vaucher’s life has always revolved around her tremendous work ethic for art – stretching back as far as she can remember.

Her grandfather – but not her parents – was artistic but it’s easy to get the impression that she was self-taught from an early age. "Every child draws, don’t they?" says Vaucher about her first forays into art as the youngest of her family with three older brothers. "My most lasting memory is having made a lot of Christmas cards. I must have been six or seven. I remember sitting at the table working away. And my brother did a wobbler and tore them all up. Such cruelty – it never left me. It was the first demonstration of something that was really cruel, especially as he was child himself.

"What kind of cards? Just drawings, scribblings, not much twinkle. There wasn’t really much twinkle around in those days," smiles Vaucher.

Vaucher’s upbringing in the bleak post-war rationing and poverty of working-class east London informed her enduring DIY aesthetic towards art. Creating something from nothing is wholly intrinsic to her art – almost as a philosophy or raison d’être. "It’s art in itself," she says. "And you could say that relates to the war – I was born a month after it ended. It was still wartime – there was still shortage. My father was an absolute genius at making something from nothing. Like me, he would pick stuff up off the street. I still do, and use it.

"He made all our toys. He’d find bits of wood, bring them home and put two together but with a step, says Vaucher starting to smile at the recollection, "then we’d hobble around on them like stilts!" A chef then boiler cleaner by trade, Vaucher’s father apparently invented an early version of what became to be known as streak racing for kids’ toy cars: "Once he came home with all these long piece of ply," recalls Vaucher. "Really long. You could put them from one wall over to the next. He said, ‘go and get all your toys!’ And we’d race them along while mum would be sitting underneath it all knitting.

"He made a golf course in the garden. He got all mum’s eggcups and sunk them down into the ground and then he made these putting things. He was brilliant. He’d never throw anything away. He was a very inspiring man. My mum was as well. She’d always unravel jumpers and re-knit them so there were no holes."

It may be back in vogue because of the recession, but that wartime make-do-and-mend culture seems a thing of the past now. Grassroots recycling and reusing was once simply common sense, before an industry was built around it. That fundamental understanding of permaculture seems like a distant memory, basic skills that only out-of-touch grandparents would practice. The inability of a generation to create or cook without an expensive magazine for instruction, or a hobby shop for the requisite overpriced tools and materials. Is that practical DIY initiative dead? "Not in our house it’s not!" avers Vaucher. "I love making something from nothing, and I’m good at it. A lot of people can’t do that – they can’t adapt."

Something from nothing is where we came in: the enthusiastic art of children. At the one-time Crass commune of Dial House, Vaucher runs summer art days for local kids. As with Crass, action – as activism – is as important on a practical level to Vaucher as the lyrics or art: "We have art students visiting the house saying they’re doing PhDs or Masters and whatever in art. I tell them, ‘just get on with it!’"

Children, the innocence of youth and the fleeting changes of their looks is a recurring theme in Vaucher’s artwork. In 2007, her Children series of portraits was based on deliberately androgynous kids who have seen too much too soon, "whether it’s domestic violence or rape," she explains. More recently, Vaucher produced Angel for this year’s Raindance film festival, an ‘exercise in visual perception’, the 40-minute film features a barely-moving portrait-like image of a young girl, caught for a moment in time before maturity catches up. The bittersweet nature of these works seem at odds with Vaucher’s own childhood which she describes as happy and enormously positive – her parents were supportive of her talent for art. For someone with so much warmth and love (she spends the interview anxiously fretting about close friend Penny Rimbaud’s illness) and as such a caring, almost maternal type, it’s a surprise to learn Vaucher has never had kids of her own. "No, I have no children of my own, and even if I did they wouldn’t be mine," she later tells me. "I don’t regret not having children."

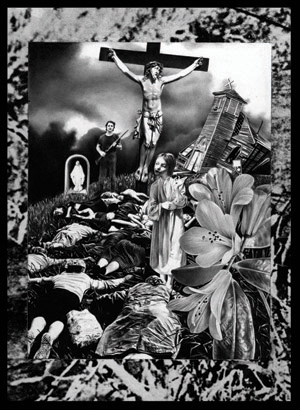

Nevertheless, children are integral to her art. And it was a historical tragedy involving children that would later be responsible for her most renowned anarchic art. Whilst finishing college in 1966, Vaucher was hugely affected by events following the Aberfan disaster, when the collapse of a huge slagheap by a Welsh mining village killed 144 people – 116 of whom were children attending primary school. The ensuing outrage around "the dishonesty and corruption" prevalent amongst private industry and politicians at the time (not that dissimilar to this year’s denouement of the Hillsborough tragedy) politicised Vaucher for life.

Five years earlier, Vaucher had started her career at the South East Essex School Of Art & Design in east London’s Barking, which, appropriately for Vaucher, specialised in the applied arts: drawing, print-making, letterpress. And it’s where she met fellow student Penny Rimbaud walking down the corridor. "He looked different – he had a parting on the side of his head and a tweed jacket on," recalls Vaucher. "I remember seeing him in the corridor and thinking ‘hmm, he looks a bit smart’ and he spoke smart as well – because of the totally different class background."

Penny was also responsible for Gee’s name. Vaucher is a family name, but she’s never been keen on giving her original first name. "Your real name is what you adapt to, isn’t it? In fact Pen gave me the name and it got shortened in time. It used to be ‘Grout’ at college. I was moaning about something and he said, ‘stop grouting’. And I said, ‘you mean grousing’. Anyway, the Grout name stuck and everyone started calling me Grout, and then it gradually got shortened to Gee."

At college Vaucher threw herself into her work, spending an enormous amount of time in the life drawing room. Left to her own devices, her initiative and self-motivation came into its own. "They respected what you were doing and let you get on with it. From the start I didn’t want any help. I hate people telling me anything – in the sense that if I don’t ask. If I needed help I’d ask for it; I need to make my own mistakes, I really do. And I did. I loved drawing. I spent all my time in the life room. Nowadays everyone uses computers."

While Vaucher uses a computer as a tool for publishing/layouts (she’s self-taught in Photoshop and InDesign, unsurprisingly), it’s not something she’ll use instead of traditional materials. "The computer has its use, like any new invention. But to throw all the knowledge away from before, that’s foolish. You take things with you. I have a use for the computer but it doesn’t fucking run my art. I like to get in the studio and throw things around; splash paint around and tear paper up. It’s a physical thing."

Like many students, college was where Vaucher first became involved in activism. But perhaps not the kind of campaigning you’d associate with students nowadays – in fact she fought to spend more time working. "It was my life," says Vaucher. "The college shut at 6pm and I fought to keep it open until 10pm then fought to keep it open at the weekends – which it did."

Activism of a more world-changing nature would emerge from the 1960s counterculture movement, born from student politics across Europe and the USA. There’s no doubt that being involved during 1961-1966 must have been an incredible cauldron of ideas and an exhilarating time to be at art college. "Oh yeah. It was all happening. Hockney was still at college and inspiring. It was a great time. I’ve always loved Hockney. I still love him even though I don’t like some of his work. I love his spirit and his passion. I didn’t like Picasso at the time," says Vaucher on her other major influence. "It took me a long time to warm to Picasso then it just turned on like a light."

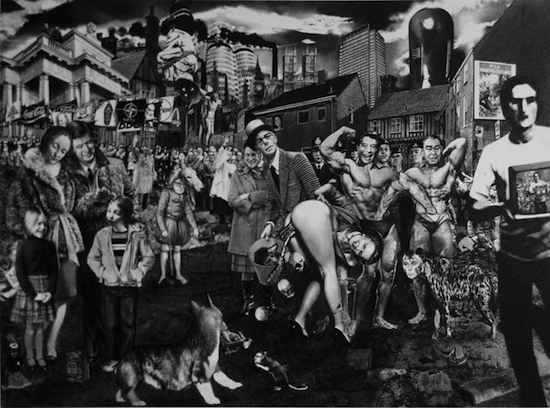

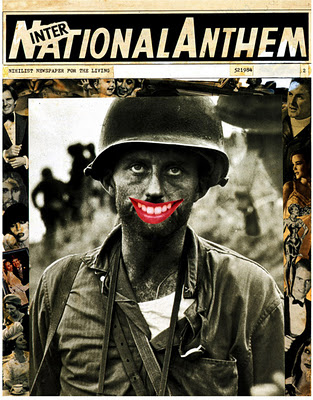

Picasso provides one of two quotes which Vaucher uses in her preface to her new compilation of punk rock art Punk: An Aesthetic. Tellingly, the other quote comes from RD Laing, an unorthodox psychiatrist whose views on the causes and treatment of mental illness were informed by existential philosophy. Such views are only now beginning to receive mainstream acceptance. Both of the quotes sum up Vaucher’s influences and inspiration: they may sound like unlikely bedfellows but together they epitomise the originality and abstract/surrealist, schizophrenic unease of her collage work.

The publication of Punk: An Aesthetic accompanied an exhibition that recently ran at London’s Hayward gallery. The book also features Linder Sterling, Jamie Reid, Raymond Pettibon and John Holmstrom among others, with essays by Jon Savage and William Gibson. Despite being included in many exhibitions featuring other artists and having her own dedicated exhibitions across the States in New York, San Francisco and LA, she’s never had one in the UK. But it’s not an issue for her. Vaucher may be independently-minded with regards to the art industry to the point of being frustrating, but she is modest to the point of being maddening.

Is art still art when it commands the prices of Damien Hirst? Can he still legitimately call himself an artist?

"You could say that about Picasso," says Vaucher diplomatically. "He spent the second half of his life as a millionaire many times over. Could he still make art when he had money? I think he did, yes. But then he had that integrity to start with – and he did everything [himself]. He didn’t have other people doing his art. I have problem with that – Hirst has a team of people doing his art."

Like a factory?

"Yes – but then that’s another form of art. Andy Warhol probably set the trend. The Factory [Warhol’s studio] was a factory – turning out silkscreens. They all have a value but whether I would choose to go that way is another matter. It’s another way of thinking, another way of driving something. Warhol was into high society and money – that’s how he made it. If you’re in it to make money, that’s the best way to go about it. It seems integrity doesn’t really matter any more. It does to me but I’m not interested in making hordes of money. It’s not the object."

Somewhat predictably, Vaucher is difficult to pin down regarding a description or overall summation of her style of art. Wildly distrustful of any hegemonic or hierarchical art ‘movements’ or categories, the general default epiphet used to describe Vaucher is a ‘political artist’. But such a term, she maintains, is tautology: "All art is ‘political’, all aesthetic is ‘political’. How do you draw the line? I used to do paintings that were pontillist, abstract. I used to try it all, y’know, to see what all of it was all about.

"Everything is to do with art. My work has always been about the psychology of action, or being – the way people go about things, or the way they solve problems – or the way they add to them because of the way they’ve tried to solve a problem.

"I’ve never thought that way," says Vaucher, incredulous at the very idea. She likens her logical thinking to a basic task such as making a cup of tea if she’s thirsty – and the steps she must take in order to end up with one. "How can I solve this problem with the little that I might have?"

This basic ideology emphasises Vaucher’s practical attitude to art. Her approach underscores the DIY ethic that would later become synonymous with 1960s counterculture and the hippies, then later with Crass and anarcho-punk. It’s also an artistic psychology that has a wider bearing on her life as well as her work. "It’s all about sensitivity, it’s all about truth, honesty, understanding the foundation of the problem. How far do you go back? Do you just stem the wound with a plaster or do you go back further and see what’s creating it? It’s the same with your health. It’s holistic. Because life is holistic isn’t it? You can’t just take one little bit. Everything to me is so linked. You have to step back and see where it all comes from… it’s unending."

The reissue of Crass Art And Other Pre Post-Modernist Monsters by Gee Vaucher is out now, published by Exit Stencil Press; Punk: An Aesthetic, edited by by Johan Kugelberg is out now, published by Rizzoli

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more