In an article for Time Out in March 1982, Pete Townshend wrote of his initial encounters with the young Paul Weller. Despite both being of the mod ilk, the pair clashed on the importance of breaking the American market – among other things. The Jam’s frontman, though a fan of early Who, saw the band then as one of the "establishment rock acts" that punk had burst out against and wasn’t interested in Townshend’s seemingly commercial motivations. Townshend, both in admiration and in question of Weller’s white-knuckled grasp of his principles, wrote: “As I approach my forties I find it harder to give my time to the proudly independent desperation of the young. I tend to think hard before committing myself in a song or an interview the way Weller does without fail. And yet he feels old at 24. Will it happen to him too?”

It was just a few short months after Townshend’s words were published that Weller announced to his bandmates that The Jam were over.

Punk was completely dead by 1982. The surviving bands who had risen from the working classes to rebel against stadium rock were now looking at much bigger venues, bigger money, and in Weller’s case, a bigger moral dilemma. The Jam’s energy was still electric, and Weller’s political convictions still seethed, yet he was becoming more and more aware of the contradiction in becoming an ‘over-25’ idol of the dissatisfied youth.

Beyond that, Weller’s song writing had become more sophisticated, his voice both on paper and on record had gained range and depth. His musical direction was also shifting. His intensified love of 60s soul of the Stax and Tamla/Motown variety had given him a vision for The Jam’s next album, one he would ultimately struggle to actualize.

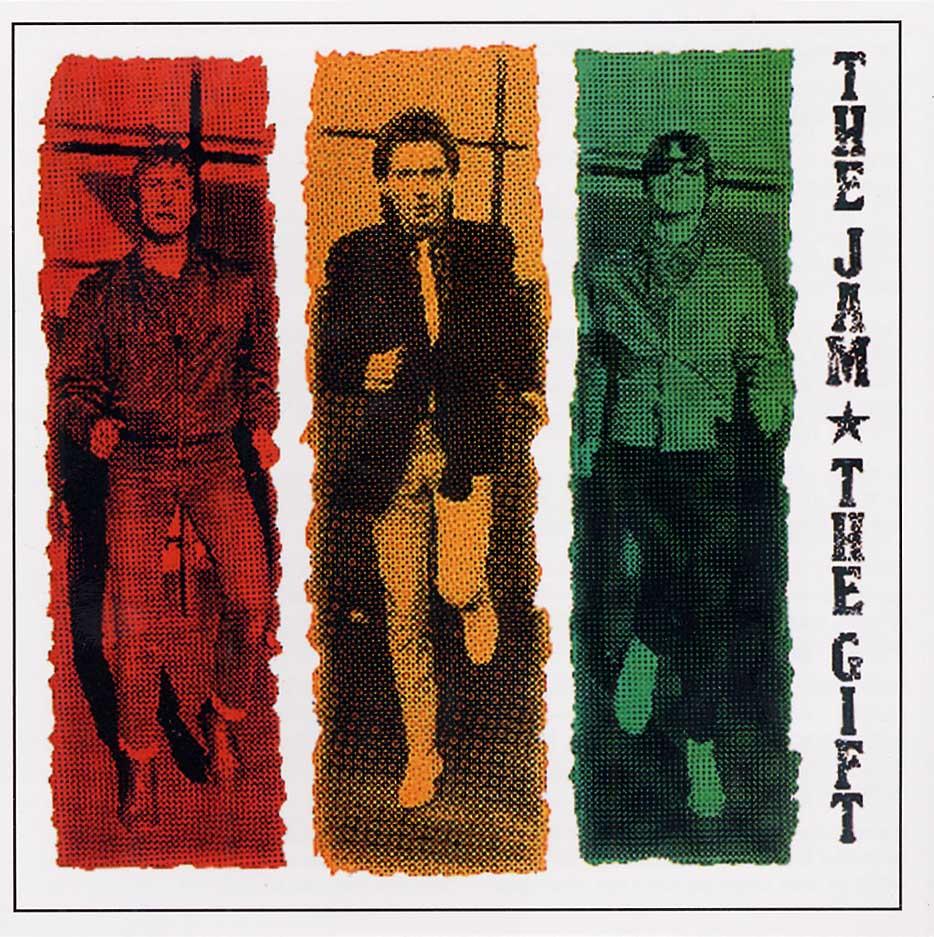

Their sixth and final record, The Gift is only barely a Jam album, so it’s fairly unsurprising that many fans of the band wouldn’t rank it among the group’s best. Yet for the Paul Weller fan – who names himself a fan of both The Jam and the Style Council, as well as the man’s wildly varied solo career – this is a cornerstone of his catalogue. It’s Weller with one foot out the door, only a Jam album with a Jam sound because Bruce Foxton and Rick Buckler are making themselves known. A rhythm section so distinctive that their timbre comes through on even the most divisive of Weller’s musical sidesteps.

The band may have been tighter than ever before but Weller was gagging to loosen up. He was realising that he had not only outgrown his fanbase, but also his band’s line-up.

Despite suffering the beginnings of Weller’s self-exile, The Gift has some undeniably Jam-esque moments, such as the opener ‘Happy Together’, bereft of the horns that feature on much of the record and also featuring the familiar serrated guitars and front-mixed Rickenbacker bass that characterized the band from the start. ‘Just Who Is The 5 O’Clock Hero’ perfectly illustrates lyrically the challenges faced in the lives of the modernly mundane – in this case inspired by seeing his father John coming home from work every day “covered in shit and aches and pains” – in the way that only The Jam’s Weller could. In contrast ‘Carnation’, a realization of the innate dark side in everyone, wears its anguish on its sleeve with mournful chord changes. Lastly, the often-overlooked ‘Running On the Spot’ has everything an excellent Jam tune should, but polished to a tinny sheen. The rhythm is so solid and the harmonies so tight, all over the usual potent social observations such as: “Out in the pastures we call society/ You can’t see further than the bottom of your glass”.

And then there are the tracks that clearly show Weller struggling with the limitations of The Jam in articulating his new direction. The most obvious of these is ‘The Planner’s Dream Goes Wrong’. Appropriately prefixed by Foxton’s clunky ‘Circus’ instrumental, ‘Planner’s’ is indicative of the bubbly positivity abstracting a truly grim political point that would be common in the Style Council era with tunes like ‘Come To Milton Keynes’. Yet the song falls flat on its face with a calypso beat and steel drums manhandled into the mix, overpowering the message.

Weller’s message was also changing in his songwriting. Themes of unity pervade the usual disenchantment; he’d begun to offer suggestions and solutions along with his social commentary – seemingly more confident in his political leanings. ‘Trans-Global Express’, the spoken word call-to-arms is certainly a sign of what was to come, but the lyrics are so buried in the production that they are virtually inaudible. Still the Stax-style romp laying over it is great fun, even if the words are telling the world to strike and “see the hands of oppression fumble/and their systems crash to the ground”. Perhaps that political nerve still had a ways to go.

But The Gift has its outright successes, where the soul influence found its place among The Jam’s sound. Oddly, they all seem to be accompanied by some manner of direct lift from another tune. ‘Town Called Malice’ for one, nicks the beat and bassline from The Supremes’ ‘You Can’t Hurry Love’, but pairs it sublimely with a cutting look at Thatcher’s Britain. The other tune on ‘Malice’’s double A-side single, ‘Precious’ gives more than homage to ‘Papa’s Got a Brand New Pigbag’, but again the funk bassline seems to suit Foxton perfectly. Then there’s the title track, infectiously soulful with bubbly lyrics full of moving and grooving, topped off with a riff-lift from the Small Faces’ ‘Don’t Burst My Bubble’.

Set apart from the others is possibly the highlight of the record: ‘Ghosts’. A testament to Weller’s now finely tuned soft touch, beginning with sliding bass and a low register whisper, joined by brass, hand claps and a soaring vocal – beautifully expressive of the pursuit of happiness he’s encouraging.

It’s been 30 years since The Gift was released and, as is customary, the record has been repackaged and supplemented as an anniversary issue. The ‘super deluxe’ package out now is comprised of three CDs and one DVD, including demos (often recorded entirely by Weller himself), instrumentals and alternate versions of the original album tracks as well as b-sides and many other additional pieces relevant to this particular era of The Jam. Disc three contains the live set from the Jam’s Wembley appearance on December 3rd 1982 and the DVD boasts a collection of promos, live performances and TV appearances from the time. All in all it’s about as complete as you can get when it comes to showing where the Jam were as a band, and where Weller was going.

Importantly, the collection includes the two 1982 singles that were not on The Gift’s tracklist: ‘The Bitterest Pill (I Ever Had to Swallow)’ and the band’s swansong chart-topper ‘Beat Surrender’. The former of these is a real precursor to the Style Council – a point cemented by the demo (also in the collection), which is so completely realized that Foxton and Buckler were redundant by the final take. Similarly, soul covers ‘Move On Up’, ‘War’ and ‘Stoned Out of My Mind’ have more a Weller stamp than a Jam one – it’s even been reported that Weller used a drum machine for the latter two.

But if anything could have suggested a future for The Jam, it’s the punchy ‘Pity Poor Alfie’, which appears on the new edition of The Gift in in two versions: the first undulating into ‘Fever’ and the second, a swing number. It stands out from the rest of the soul numbers and from the group’s usual sound, almost big-band-like; yet there’s something intrinsically Jam-like about it. Buckler and Foxton are on incredible form here, certainly enough to bring curiosity on what could have come next had they remained a trio and just applied a touch of the Style Council revolving line-up on the next record.

However, while I’ve been happy to see many bands hop the reunion bandwagon in recent years – especially the ones who either because of age or geography evaded me previously – I hope that The Jam never do. This, simply for the reason that respect for the group’s legacy and for Weller’s convictions is very much tied up in the circumstances of their demise. The Gift is inerrable proof of his foresight.

In truth, I don’t think The Jam will come together again. Anyone who believes otherwise need only look to Weller’s dark ages in the early 90s following his reviled too-early romp with house music, which saw the Style Council dropped from their label and subsequently disbanded. By all accounts he was a man lost, confused and distrustful of the instincts he had relied on so heavily throughout his career. Yet even among that insecurity, the idea of reforming The Jam for what would have undoubtedly been a massively lucrative and fanatically welcomed outing, remained unappealing to Weller. Keeping in mind that the man has yet another solo album hit under his belt from just earlier this year, I think all of the ‘just Jam’ fans out there shouldn’t hold their breath. Besides, as one of Pete Townshend’s cutting, apt observations of Weller’s nature concluded: "I have never come across any other artist or writer so afraid of appearing hypocritical.” It’s Weller’s greatest personality flaw, which has also proved to be his greatest artistic strength. Just as he couldn’t bear being an old man leading the young, he also could not claim to be a progressive, ever-changing artist if he repeated himself. The Jam ended with a number one album and number one single, a death with dignity for which we should all be grateful.

The super deluxe box of The Gift is out now on Universal