Call Me Kuchu (‘kuchu’ is slang for gay in Uganda) is a powerful, award-winning documentary by first-time filmmakers Malika Zouhali-Worrall and Katherine Fairfax Wright. It deserves all the attention it can get for shedding light on the struggle of homosexuals to be accepted in that most homophobic of countries, Uganda. The film reminds us why we cannot remain complacent with the freedoms we have, detailing in particular the life of key gay activist David Kato, who we see fighting a daily battle to win rights for gay people, including opposing the notorious Anti-Homosexuality Bill which proposes the death penalty for ‘aggravated homosexuality’.

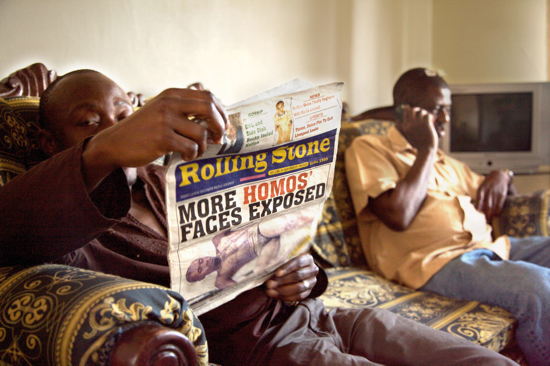

Kato, the first openly gay man in Uganda, is an extraordinary person full of humour, bravery and compassion. He makes for a compelling subject. The film also follows fellow gay activists Stosh, Naome and Victor as they struggle to live their lives with the daily threat of violence. And we meet Bishop Christopher Senyonjo, dubbed the Ugandan Desmond Tutu, an unlikely hero who is helping the gay community. We also hear the horrifying views of people like Giles Muhame, managing editor of Ugandan weekly tabloid Rolling Stone (nothing to do with the outraged American magazine), who unashamedly condemns homosexuals and prints their photos in his paper, encouraging violence against them.

I talked to the documentary’s co-director and producer Malika Zouhali-Worrall about gaining intimate access to the activists’ lives and the steps being taken to educate different communities…

How did you come to be involved with this story?

Malika Zouhali-Worrall: We were just very aware that the main stories we were hearing about LGBT issues in the US and in Europe were mainly around same-sex marriage and they were very western-centric. Whereas we’d become increasingly aware that there were LGBT communities in the global south who were having to deal with much more crucial issues, and in some cases issues of life and death.

We ended up focusing on Uganda partly because we’d heard about a transgender LGBT activist called Victor Mukasa. A few years ago his home was raided by the Ugandan police and all his computers were taken and he decided he wasn’t going to stand for it. And he sued the Ugandan Attorney General in a Ugandan court and won his case of police harassment, which was phenomenal. We were blown away by the idea that there were these activists on the ground who were courageous and determined enough to do something as gutsy as that. And that there was a judicial system that was independent enough to be able to rule against government in a case. And all of this going on, of course, while there was these horrible sodomy laws on the books that meant that LGBT people were being arrested and imprisoned.

Then we were introduced to David [Kato], before we’d even gone to Uganda we had a phone conversation and he just told us that we had to get there as soon as possible. He was the first person we were met when we were there and he basically introduced us to the whole community and told us about the people whose stories we should try and document.

Were all the people in the film happy for you to be telling their story, given the dangers of being outed?

MZ-W: Essentially in order for us to follow anyone intimately they had to be out already or had been outed. It would be just too risky to film a lot with anyone who wasn’t . So all the main characters wanted the opportunity to tell their own story on their own terms, and have people understand them for who they really were, rather than as these strange and horrific monsters that people would describe them as.

Your film shows the horribly callous attitude of government officials and people such as Rolling Stone managing editor Giles Muhame. How hard was that to witness?

MZ-W: It was definitely difficult. Pretty early on we managed to just switch off. We figured out that being too emotionally engaged during those kind of interviews didn’t really help, because we didn’t want those interviews to be debates between ourselves and the people. We actually realised that all we wanted and needed was for them just to describe their motivations and opinions and what they were doing. In order to do that we realised the best thing was just to ask the questions, and there was a certain need to numb ourselves a little throughout the whole process.

I found the Bishop Christopher Senyonjo to be one of the most courageous and inspiring characters. How did you come to meet him?

MZ-W: The Bishop was someone we were aware of really early on just in our research, because he’s such an incredible person. So I actually spoke with him as well as David by phone before we went to Uganda for the first time. We knew from very early on that we had to include him just because he was the least obvious character: he’s this straight, 80-something-year-old Ugandan bishop who’s decided to defend the LGBT community. So we knew before we’d even met him or spoken to him that that was pretty incredible, and that we had to get an interview with him.

The film has won numerous awards and had a great reception, but how hopeful are you that it could really make a difference for gay rights in Uganda and even Africa?

MZ-W: That’s definitely a big component of the distribution strategy we’re working on right now, so we’re really figuring out partnerships to use the film as advocacy on multiple levels; Uganda to start with, and to do that we’re partnering with Ugandan activists. But we’re also working to partner with international human rights and LGBT organisations, to incorporate the film into training for LGBT/human rights activists around the world, because we feel like parts of what these guys are doing in Uganda could be applied elsewhere.

In the US and Europe we’re partnering with organisations to bring the film into religious and especially Christian communities so that they can begin to think about their relationship between Christianity and LGBT acceptance. Especially because we want some churches to be aware of what their pastors are saying in developing countries. We’ve also got great partnerships with Amnesty International UK and that’s brilliant because they do incredible work through their LGBT network. We have a website with them, so we’re hoping to really develop that partnership over the next few months. There’s a lot going on.

I think it would really help for religious communities to see this film.

MZ-W: We really hope that the film – and a lot of people have said this to us – that the film could potentially help people. Especially people in poor environments who are used to just reading statistics and reports on the issue, help them think about the fact that this is about human beings and individuals. We’ve also been thinking about screening it for people who are key policy makers in Europe and the US and international bodies like the UN. It feels like there a lot of ways it could be used for crucial advocacy.

Call Me Kuchu is in selected UK and Irish cinemas now; for a full list of screenings check the Dogwoof website.