Don’t read the Metro. Each page you turn will inversely affect your poetical ability. Even as a guide to the state of the media it is at best second hand.

In Stevie Smith’s 1949 novel The Holiday, the narrator is annoyed to share a carriage with a man who is reading a book. Why can we no longer sit on a train and simply think, she wonders. Why do we need constant distractions? But she is curious. She tries to see what book he is reading, what book could be so gripping that he cannot bear to leave it even for a train journey. It turns out to be a soft porn novel and a prediction of the future of travel. A future of packed carriages rustling to the sound of turning free ‘news’papers and bassless beats clicking out of mobile phone headphones, while adults violently thumb computer games or studiously slide the ‘pages’ of their electronic readers loaded with the illustrated version of 50 Shades Of Grey.

In 2012, the train is no place for the silent thinker. Just reading a book that is not self-help, the Koran, the Bible or other best-seller is a start towards marking you out as a better breed of traveller.

Travel often and often alone. Find the corner seat, sit back and observe.

Avoid misanthropy. ‘Stage’ poets love the comedy commuter-rage, particularly about the tube. You know? How unfriendly it is, with its ever present smell of armpits? The tube does not smell of armpits. Kat Francois uses this start to lure us into some sharp observations about race and people’s manipulatable perceptions. Zena Edwards begins her epic poetic investigation into anger here. But the best performers don’t make a whole piece out of their comic-hyperbolic suffering in a cartoon of a stuffy fart-festering carriage.

‘Page’ poets are often no better. Many a book-and-lectern reciter enjoys the Larkin-esque moan from behind glazed windows, observing the passing of sad and futile lives. Or they may shudder behind their Martin Amis novel at the hooligan football fans in whose sadly degraded company they found themselves one cold and care-worn evening. Know thyself, is the tannoy message at Delphi Parkway.

Talk to strangers sometimes and let other mad people talk to you. If you are a poet, you probably have your own mental health issues, more or less resolved. You probably understand these people in a way that will frighten you. They will impress you with their prophetic truths and also scare the shit out of you. “Abandon him and you must make your own / House of incinerating madness.” They make good poetry.

Say ‘excuse me’ when people are in your way. Ask for directions when you need them. Walk up the moving escalators. You might not necessarily be in a rush to get anywhere (if you are a poet, you are unlikely to have work to go to) but you should wish to have some agency over your travel.

Graffiti advertising posters amusingly and politically. They are asking for it.

On the last train from Brighton to London, sit in the first class carriage with the frosted glass doors. Open the windows and a can of beer and light up a smoke. Clean up your mess afterwards.

Cautiously celebrate the conveyance that coincides the strangers who travel together. The earth keeps spilling out with people. That you know some of them and not others has little to do with your conscious choices. On buses and trains, we are not alone and it is this fact, this proximity to others, that means (note this) there is no public transport translation of ‘road rage’. When ranting occurs it is done, most often, with a degree of consciousness of the public audience for whom it is intended. It is drama composed, freeform rant as public artform, not private tantrum indulged. We laugh kindly at small misfortunes, brush legs accidently, pass the time of day incidentally, cough germs at each other, flirt more or less successfully with eye contact, carry bags and pushchairs for struggling mothers.

In the samesame humdrum of the brandscape, observe the curved brickwork of the tunnel, the ringing metal that carries the wheels, the tar-grouted asphalt of the road out the window. Adverts and safety messages will thrust themselves at you – grabbing you from the backs of seat, stabbing at your eye level and booming out in automated drone recordings. This assault on the senses pushes us to shut out the world around us. It is sensible to avoid listening to brainless security warnings, to turn blind eyes to messages meant to seduce us with promises never to our advantage. Those begging our attention are dumb and faceless; it makes sense to bury our heads into inner space. This is no place for the poet, however. Observe the materiality beneath the photoshopped coding.

Be considerate. It is, after all, public transport.

“Caz, I said, when I am with people I do not feel so cold. I like to sit in the tube train to watch the people and be watched. The light and warmth of the train bring the faces to life. They are alive alive-o, that before was wandering in a desert of night dreams with landscapes.” – The Holiday, Stevie Smith

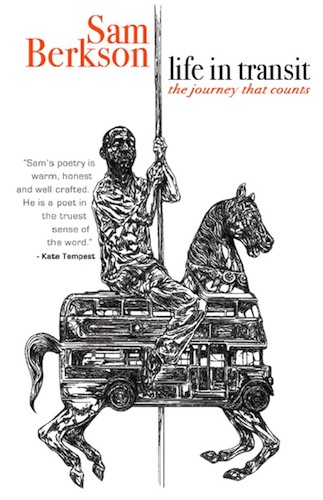

Sam Berkson’s book of poems and prose dealing with travel and transport, Life in Transit, is out on 5th November published by Influx Press and will be celebrated with a launch event at Arcola.