It’s no surprise that Orson Welles was drawn to adapting The Trial for the screen. The twists and frustrating turns of his career over the preceding two decades must’ve left the portly polymath feeling a powerful sympathy for Kafka’s hero Josef K: tortured, taunted and at the mercy of a mysterious higher power, with no hope of deliverance. Having established himself on stage and radio, Welles’ signature work Citizen Kane (1941) is now recognised by almost all students of film as a key leap forward for American cinema, expanding its storytelling vocabulary with its bravura use of camera and lucidly experimental editing techniques, but his ambitious efforts weren’t so warmly embraced by audiences nor, by logical extension, the studio machine.

His subsequent career in Hollywood was a portrait in frustration and disappointment. Most crucially, after it ran over budget and schedule, his next feature for RKO, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), was taken out of Welles’ hands and finished by the studio, who sliced away almost an hour of footage from the writer-director’s original rough cut and changed the ending. Compounding this insult, the missing footage was later lost forever, cheating Welles of the opportunity of restoring the movie to his intended vision after his work was rediscovered and lauded by the Cahiers du Cinéma generation, a desire he nurtured enough to have considered reshooting the missing scenes in the 1970s, while the principal cast was still alive.

Welles’ experience with The Magnificent Ambersons is indicative of the frustrations he would suffer in the years that followed, the master storyteller denied the opportunity to use his skills freely, or even at all, by the Hollywood establishment. He chose a self-imposed exile, moving to Europe where he made money as an actor, struggled to finance and complete an adaptation of Othello, and was removed from the edit suite of 1955’s Mr Arkadin by the producer, again as his quixotic grasp for perfection saw the film fall hopelessly behind schedule.

One can imagine how an artist with as well-developed an ego as Welles chafed under such indignities, restrained from completing his visions to his satisfaction by circumstances even he could not control. As his experience on Mr Arkadin proved, even Europe – which had first hailed him as a cinematic visionary, and which he had so passionately embraced after leaving America – would ultimately thwart him just as painfully as Hollywood had done.

He undertook The Trial following another brief and frustrating sojourn in Hollywood: hired to co-star with Charlton Heston in the late-era noir Touch Of Evil, Welles stepped behind the camera after Heston lobbied for such as a condition of his agreeing to appear in the picture. Universal Studios subsequently recut and reshot Touch Of Evil before release, just like RKO had done to The Magnificent Ambersons the previous decade. Welles returned again to Europe, and spent much of the 1960s working on a Don Quixote film he never completed – a project financed, in part, by his work on The Trial, produced by Alexander Salkind and his father Michael.

Orson Welles’ take on The Trial is a powerful – almost overpowering – vision, its visceral impact deriving from the dreamlike mood it establishes. No, not dreamlike – nightmarish. Not even nightmarish – it is a nightmare, playing out like a nightmare does, a work of paranoia (albeit of the ‘just because you’re paranoid, don’t mean they’re not after you’ sort) that, with each subsequent scene, doubles down on its creeping sense of terror. A uniquely banal terror, perhaps: there are no ghouls, no monsters, no moments of sudden jeopardy thrown in K’s path, but Welles’ film depicts a descent into terror, as K is ever further hemmed into a pathway that leads him inexorably towards a grisly end that’s nonsensical, maddeningly bureaucratic, and entirely inescapable.

Like a nightmare, little makes sense, and little is explained, Indeed, this absent explanation for what is going on, why all this is happening, is like a morsel of cheese at the end of the maze Josef K powers along which has, unbeknownst to the subject of the experiment, been removed by the scientist. Anthony Perkins is perfect as K, establishing a sense of sustained panic that almost exhausts across the picture’s length. He’s an ideal extension of the audience, seeming as helpless and befuddled by his fate as we are, even as he works to find answers, confront his accusers, and actually find out what the charges are.

If the narrative is disjointed, that’s doubtless on purpose, to give us a sense of K’s confounded anguish – again, like how a nightmare rarely runs like anything but an impressionistic bustle of fears. But these gaps of logic in the narrative don’t hurt the film, as its catalogue of disturbing sequences, its dark vignettes, deliver the story with imagery that haunts, days after screening.

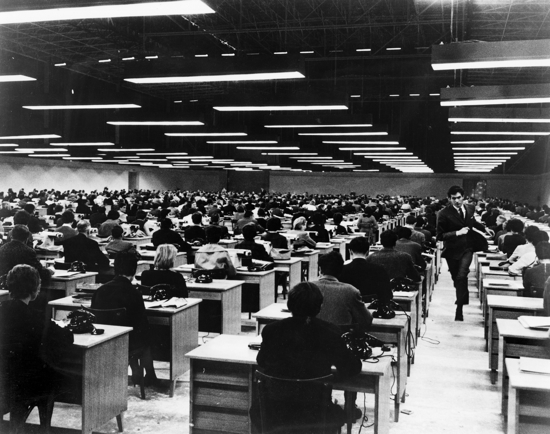

Welles’ production wandered across Europe for locations, filming K’s workplace in the former Yugoslavia – in a cavernous exposition hall in Zagreb, an alienating and dehumanizing space. Welles hired 850 secretaries to hammer away at 850 typewriters, a vast faceless mass that’s seemingly collectively oblivious to their workmate’s woes. As K confronts his neighbour’s landlady in search of answers for his scourging, the pair slope across a stark post-industrial landscape of brutalist social housing, grand and lifeless and blank tower blocks against an oppressive winter twilight. It’s a vision straight out of 1950s anti-Soviet propaganda; perhaps it’s worth noting that the director was denied permission to film scenes in Prague by Czechoslovakia’s ruling Communist government.

Meanwhile, budget concerns prevented Welles from shooting interiors at the Bois de Boulogne studios in Paris, ending up instead at the Gare d’Orsay, but this ultimately works to The Trial‘s advantage. Old, dusty and worn, the abandoned railway station’s walls and pillars evoke a mouldering society, and are settings for some of the most memorable scenes. Played by Welles himself, the advocate Hastler has an office that seems equal parts a wrecked library littered with piles of books, and a wretched opium den. The courtroom where K gives a spirited but impotent speech in his defence more closely resembles a gallows, or a cattle exchange.

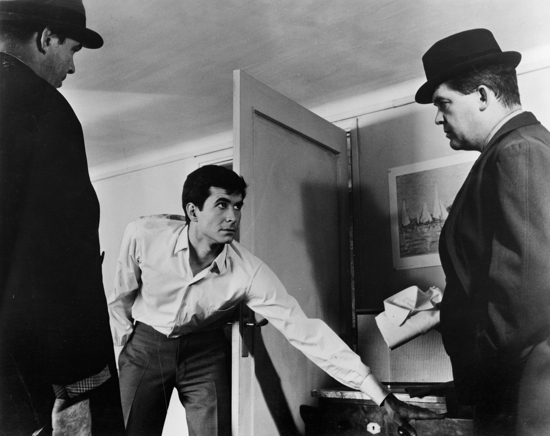

It’s the people who infest these rooms that are most disturbing, most unforgettable. Compounding the nonsensical predicament K finds himself in are the twisted pockets of humanity that surround him: his lame landlady Mrs Grubach (Madeleine Robinson), dragging her iron leg along the ground as she curses him; the silent trio of colleagues he discovers rifling through his neighbour’s possessions in search of incriminating evidence, like some morbid bizarro Marx Brothers, if they were all Harpo; the sad, old, lost, gummy faces that wander about him in the streets. They behave in ways that make no immediate sense, their veiled and unknowable motivations beyond K, and the viewer. Then there are the masses who cheer for K, at the request of his accusers, in the courtroom; the mysterious amorous advances of Hastler’s mistress Leni (Romy Schneider); the intentions of Hastler himself, the law advocate who might hold some answer to all of K’s questions, if he could only be cajoled into sharing them.

Assembled, they make up a sinister contortion of society: blind and powerless and complicit in their world’s sins, as K is when the policemen he accused of corruption are tortured and punished in his office. It’s one of the most unsettling scenes, a flash of actual violence in a film where its implication is everywhere, as the half-naked victims apologise to K for disturbing him with their howls. "He’s putting the tape across our mouths," one simpers. "Don’t worry, you won’t hear us scream."

An unsettling and powerful movie, The Trial isn’t a lot of fun to watch. The conclusion is, inevitably, disappointing – the film is better at establishing its sulphurous sense of paranoia than drawing it to a close – and its claustrophobic anxiety is ultimately suffocating. However, it’s worth persevering. What Welles achieved here was remarkable, a perfect evocation of paranoia, fear and frustration, emotions with which the director had become intimately acquainted through his filmmaking career: a perfectly Kafkaesque experience.

The Trial is out now on Blu-ray and DVD via StudioCanal.