The success of Fender and Gibson inspired the creation of similar guitar models in the Eastern Bloc, with many countries manufacturing regional variants of these global brands. One person who was central to guitar production in Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia during this decade was an instrument manufacturer called Josef Růžička. At the end of the 1950s, models he designed, such as the Arioso and Arco, stormed the Brussels Expo in 1958, sweeping up awards. In 1959, a new model, the Neoton went into production in Hradec Kralove. In 1960, guitars made under the Jolana brand were introduced in this region for the first time. Managed by Růžička, the legend says the Jolana company was named after his daughter – the instrument’s history in communist countries, where it was tough to obtain well-seasoned wood, was now inaugurated.

These models rapidly gained a great reputation as high-end instruments accessible to musicians of all skill levels. And these guitars travelled – the Futurama reached the hands of George Harrison, Jimmy Page, and Eric Clapton, in partly due to a British embargo on US imports until the end of the 50s. The Czech company was also known for its commitment to innovation and experimentation. Jolana guitars had a distinctive look complemented by a design which pushed guitar boundaries, incorporating a bolt-on neck, which allowed for easier and faster changes, and adjustable bridges, allowing players to fine-tune their instruments’ actions and intonation easily.

These guitars spread across eastern Europe, finally reaching Azerbaijan, which lies in the South Caucasus, between Western Asia and Eastern Europe. The country’s oil wealth led to the cultural development of capital city Baku, from the late 19th century onwards. Local composers and musicians experimented with traditions, styles, and genres – the music of European orchestras met the sound of traditional instruments such as tar or kamancheh, possible as a new musical infrastructure involving theatres, radio stations, a recording industry and conservatoires emerged under communism. But this mix of traditions really exploded after the war, as Jolana guitars, imported from brotherly Czechoslovakia, found fertile new ground waiting for them.

In the 1960s, musicians along and across the Caucasus adapted the instrument, inspired by traditional genres such as mugham (the classical music of Azerbaijan) and the songs and tunes of Ashiq bards. With its distinctive sound, new techniques, and playing styles, a subculture emerged defined by the Azerbaijani gitara. It became more widely known when Rafiq Hьseynov (aka Rəmiş), who played the tar modal music of mugham, popularised the instrument. He was altering the tuning by quarter tones to match local Azerbaijani scales, which set him apart from American or European musicians.

A Czechoslovakian guitar was ideally suited to this task. The way the strings were elevated between the bridge and end-pin of the hollow-bodied semi-acoustic allowed the player to bend the strings with their wrist while playing, altering the tuning by quarter tones to match local musical conventions.

Soon, more names appeared, and, by the 70s and 80s, the guitar became a national instrument in Azerbaijan. So many people played it, that it started a domestic revolution; an analog of the British rock & roll explosion of the 1950s. Soon the distinctive sound of the Azerbaijani guitar was heard at weddings, official parties, any functions at all. Some musicians would put the instrument on their knees and play it like a steel guitar, many holding the neck raised very high, reminiscent of how musicians play tar. A magnificent documentary called Gitara charts this development. The film, made by Stefan Williamson Fa and Ben Wheeler Mountains of Tongues, a collective preserving and promoting less-well-known music from the Caucasus region, also records another instrument, the Fitar, an Azerbaijani guitar model created by Fikret Quliyev.

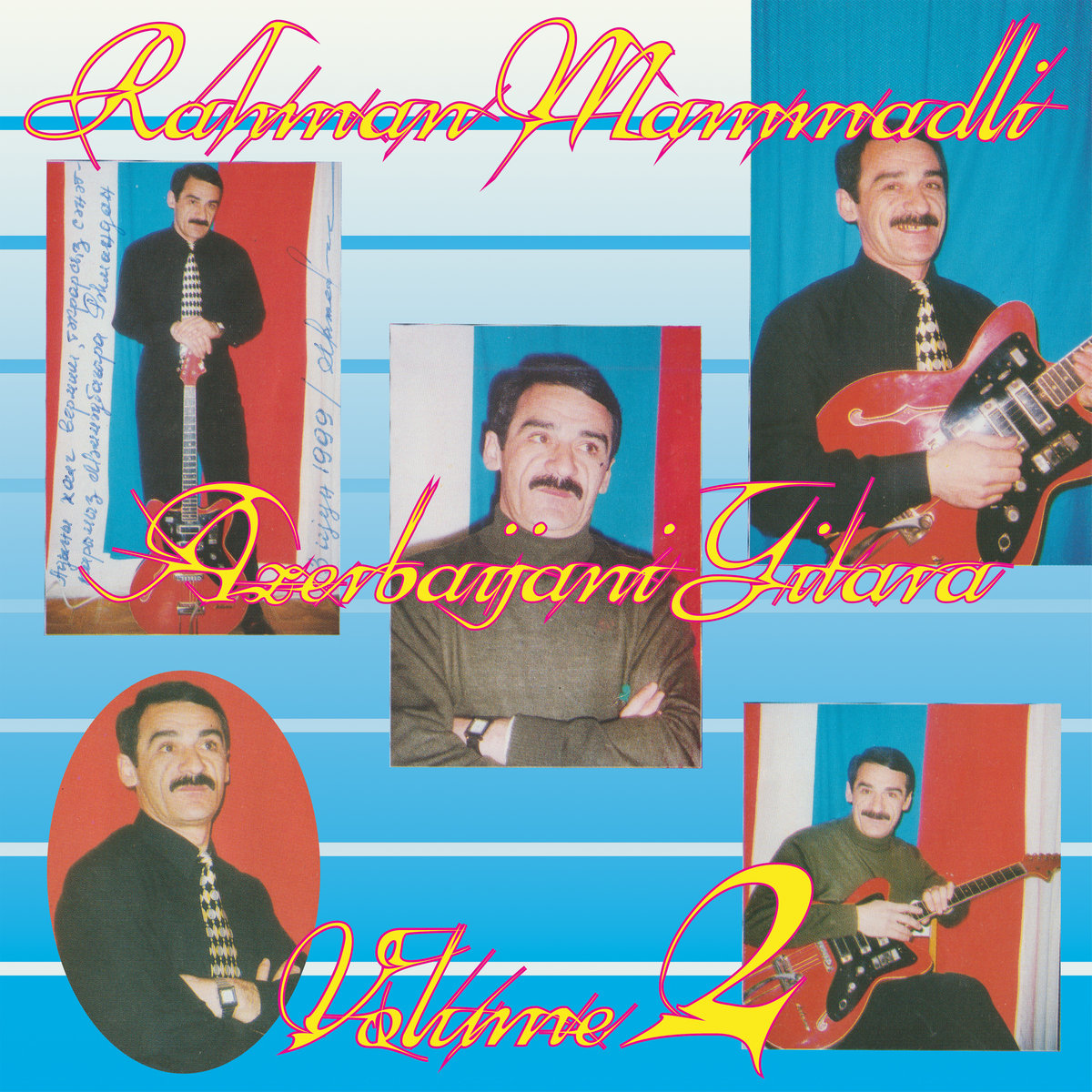

Mountains of Tongues released a self-titled album by Rьstəm Quliyev on cassette a few years ago, which was then reissued by Les Disques Bongo Joe as Azerbaijani Guitara. Each guitarist featured, forges their own path. They were experimenting with the sound of the instruments. For instance, Rəmiş was laying melancholic lyrical melodies, and Rьstəm Quliyev weaves various influences and soundtracks, Afghan pop, Spanish flamenco, and Western psych. They grew up in the Karabakh region, as did Rəhman Məmmədli, whose music is now released on Azerbaijani Guitara Volume 2.

Məmmədli puts his spin on the sound by combining it with Azerbaijani folk music. He experiments with modifications to the instrument, adding frets to facilitate playing in traditional modes. Born in 1961, he grew up surrounded by the region’s music. As a child, he played the garmoshka, a Russian button accordion, but it wasn’t until the guitar – which he taught himself to play in the mid-1970s – became his main instrument that he could tackle a whole spectrum of melodies, and he soon found himself in the Karabakh Ensemble.

He introduced distortion to his sound in the late 1970s to accurately reproduce the harsher tones of some traditional vocal styles. In doing so, he was graced with the nickname ‘oxuyan barmağı’ – the one with the singing fingers. You can hear this in ‘Xal qalmadı’ – a rendition of folk singer-songwriter Cabbar Qaryağdıoğlu’s song, where the guitar sounds almost like a vocal too. He plays fast – it’s pure maximalism – and he uses the instrument with quick movements as if it were a tar. With a guitar, you constantly change strings and make more finger movements on different octaves. But tar players tend to utilise different techniques. Məmmədli combined the two practices – in the Gitara documentary he explains precisely how he’s bending the strings by moving his wrist to get quarter tones.

The melodic line is hidden under several layers of ornamentation. The result is a sonic conundrum akin to the psychedelic guitar music of 1960s California. Məmmədli rarely composed his own tracks, instead reinterpreting Azerbaijani folk songs, mughams, and folk dances, arranging them with spacey synth chords, distorted guitar, and primitive beats – sometimes machine rhythms, sometimes using local percussive instruments like ghaval or naghara. From the outset he was attempting to bring new life into Azerbaijani tradition. In 1980, he was signed up for military service – after finishing in 1983, he would be the artistic director of the Culture House of Bilajari Railwaymen until the end of the decade. Later, after Azerbaijan proclaimed its independence in 1991, he continued playing guitar and tar, performing at weddings, on TV, and recording small run cassettes.

There is a lot of colour crammed into this compilation. Just listen to ‘Qoçəlı̇’, an escalating dense cascade, a display of virtuosity; he plays spasmodically over synth lines and then erupts into a percussive trance. Faster ‘Yanıq Kərəmı̇’ has the rhythmic freneticism of singeli, but in the accumulation of synthetic primitive beats, the guitar cuts through clearly, in jazz scales, to the fore. ‘Xarı Bülbül’ is more march-like; the guitar does not attack so vigorously; instead, it weaves expressive phrases, distorted until it starts to resemble an entirely different instrument. ‘Qoca Dağlar’ and ‘Uca Dağlar Başında’, are arrangements of repeatedly performed Azerbaijani songs, while in ‘Leylı̇can’, the musician jumps into higher registers, where his grandstanding soloing impacts more decisively.

In the 1970s, Jolana Guitars was forced to shut down in Czechoslovakia due to increasing economic pressure and political unrest. The factory was sold, and the employees were laid off, but the instrument had made its mark in the region and these models always sell for exorbitant prices on internet auctions. Production resumed in 2003. Rəhman Məmmədli is still active, too – he works as a tar teacher at a children’s music school in Fuzuli. He often plays live for hours at a stretch, and you can see these performances in electrifying videos uploaded to social media.

Last autumn opened another chapter in his musical journey making his first appearance in Europe, at Le Guess Who? festival. And now the first Western release for his music. Məmmədli’s work is the essence of a subculture in Azerbaijan centered on the electric guitar. His music combines his local heritage with echoes of surf guitar. He is now working on a new album and will return to Europe in June for a tour.