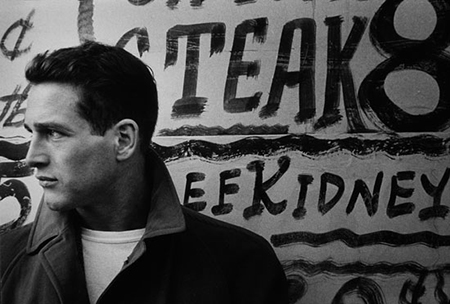

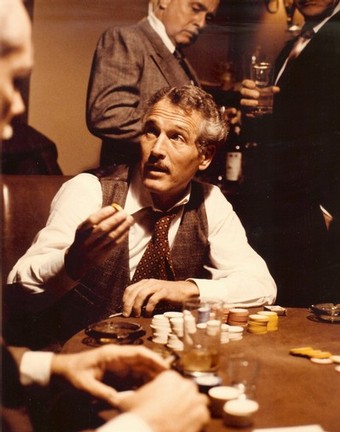

I don’t remember the first time I saw The Sting. It was, and remains, my mother’s all time favorite movie and so as a child I saw it a lot and from a very young age. For a long time it was for me the idealized version of a movie. Not being able to imagine a world in which people actually dressed that way and listened to that kind of music, it seemed like a perfect and perfectly unique universe. And Paul Newman’s Henry Gondorff was that universe’s perfect man.

Never mind that when we first meet Gondorff he’s broke, drunk and in hiding. The first lesson in manliness I learned from Paul Newman was that great men will go unappreciated. The second lesson I learned was that when men aren’t doing the one thing they’re great at (and there can be only one), they drink.

Soon enough, we would get to know Henry Gondorff and to see him as he truly is, a master of every situation. A man, it turns out, is someone who is aware of and understands the world around him, so much so that he is completely sure of everything that will and should happen. He shows no doubt, not because of hubris but because he has experience and plenty of it.

In the end, a man will come out on top. He will be victorious because he has earned victory by being in the right and by working hard (and always enjoying the work he is doing). These are the lessons in manhood Paul Newman taught me by the time I was six years old.

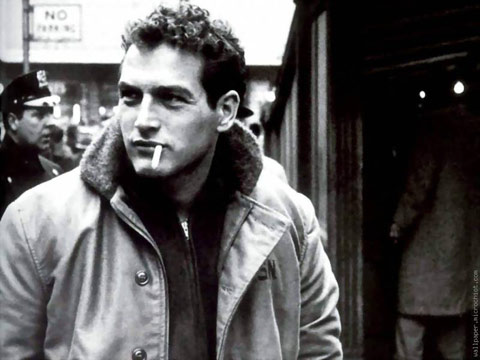

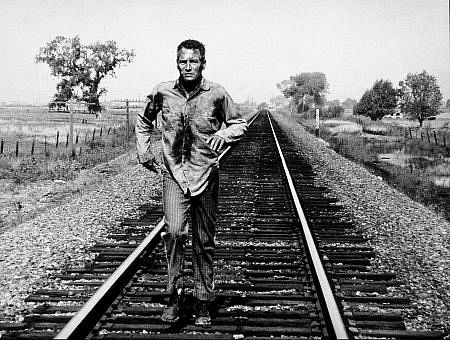

I distinctly remember the first time I saw Cool Hand Luke. I was a couple years older and, in my father’s eyes, mature enough to see and understand what was always his favorite film. Though it bore the same rating from the MPAA this was a grittier, more adult and even more manly film than The Sting. And, of course, the lessons in manliness were on a more nuanced level.

Again, our introduction to Newman is in a state of advanced drunkenness. Cutting the heads off parking meters may be a mild form of social protest but doing it with blatant insouciance is a major form of being cool.

A true man, according to Luke, is an outcast by definition because he carries and lives by his own moral code, not that of the status quo. He stands up against transgressions of this code but not in base ways. He does not rage against his enemies. He really has no enemies because he is too mature and far too self-reliant to define himself by the opinions of others.

That said, he is not against trying to impress people, at least those whom he deems worthy of being impressed. Luke eats fifty eggs in an hour on a bet. He is not simply the most popular guy in prison, he is Jesus Christ after the feeding of the 5,000. He performs this feat as a leader, not as a status seeker.

The next lesson in Cool Hand Luke comes when Luke has been worked and beaten to a point where he finally must beg for mercy. In the eyes of his fellow inmates, this makes him less of a man. But the movie and the audience know better. A man is, after all, a human. Asking for mercy makes him better than his oppressors, “the bigger man,” as the saying goes.

The final lesson is the most important and the most difficult to take. I learned it at that iconic moment at the end when Luke is framed in that church window. The lesson here is that a man can’t beat the world, at least not in any traditional sense. The world is meaner, colder and far less righteous than a true man. A man’s victory must be a moral one, one based on the principles and standards he has developed for himself.

At the end of my life (and may we all get one that spans 83 glorious years), if I can say that I have achieved such a victory, I will have lived up to the example my parents were trying to give me by showing me their two favorite films.

As I got older, I would learn further lessons from Paul Newman. The Huslter taught me that men can be foolish and cause themselves to be taken advantage of. The Verdict taught me that drinking is cool only up to a point. But, for most part, I have tried to live up to the examples Newman taught me in those first two films I saw.

Try as I might, though, I still can’t eat fifty eggs in an hour.