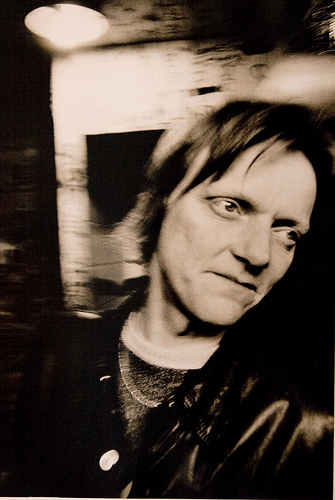

The death in June of Earl Brutus frontman and one-time Jesus & Mary Chain drummer Nick Sanderson robbed music of one its more colourful characters. Robust, intelligent and immensely funny, Sanderson is to be honoured at the upcoming Train Driver in Eye Liner tribute concert at The Forum on October 27th with a line up that features Black Box Recorder, British Sea Power and a headlining slot from The Jesus & Mary Chain.

With the event just a few weeks away and the imminent release of The Jesus & Mary Chain’s B-sides and rarities box set, vocalist Jim Reid broke his self-imposed press silence and spoke exclusively to The Quietus about Nick’s contribution to the band before discussing the highs and lows of The Jesus & Mary Chain’s illustrious career.

[For more details and tickets click here.]

How did the Nick Sanderson gig come about?

Jim Reid: “I think that William came up with the idea; y’know, when someone dies you always sit around saying, ‘Well, what can we do?’ and we immediately thought of [Nick’s wife] Romi [Mori] and [their son] Sid and stuff like that so we thought it’d be a nice thing to do. It’s gonna raise money for them, not much, but whatever we can do, y’know?”

There was talk of you recording Earl Brutus’ ‘Teenage Taliban’ at some point.

JR: “People have come up to me [since Nick’s funeral] and said ‘Oh, I hear you’re doing “Teenage Taliban”’ and I’d say that it’s not out of the question but I barely remember that song. There was a version of it that was recorded in my living room about 6 or 7 years ago or something like that and I don’t know who’s got that and I can barely remember what it goes like; I remember it was pretty good and I’m sure we could do a good version it.”

How did Nick come to be involved with the Mary Chain?

JR: “We actually rejected Nick; we were doing auditions for drummers and Nick came along just reeking of booze, basically and we were like, ’Do you know any of our songs?’ and he goes [does a very good Nick impression], “Nah…I don’t know any of your songs’ so we thought to ourselves, ‘Fuckin’ hell, this guy’s fucked and doesn’t even have any drumsticks’ but looking back on it – and I can’t even remember what joker it was we ended up employing – but Nick was one of our kinda people, you know what I mean? He was a friend of our tour manager and that’s how he came along in the first place and this tour manager kept saying that we should give Nick another go so we did. I think the first audition was between [Nick’s time in] The Gun Club and World of Twist.”

What did Nick bring to the Mary Chain?

JR: “Nick was a great drummer. That’s the thing; he was a great frontman for Earl Brutus but people forget just how good a drummer he really was. The trouble with Nick is that he loved life so much that he didn’t want to waste time practicing the drums for four hours a day like a lot of drummers seem to do; he didn’t do that. Towards the end, I don’t think he even wanted to drum at all. Yeah, he was just a great drummer but he was the most disorganised person that I ever knew and he brought that element of chaos that always kinda seemed to be around the Mary Chain anyway.”

You continued working with Nick in Freeheat after the Mary Chain broke up . . .

JR: “After the Mary Chain broke up, Nick would just…he was my mate, he was my friend and we were just sitting around the pub one night; it was me, Nick, [former Mary Chain guitarist] Ben Lurie and [one-time Gun Club bassist and Nick’s girlfriend] Romi [Mori] and we were thinking, well what are we gonna do? And it occurred to us that there was a band sat around the table so we said, ‘Let’s form a band’. But Freeheat was more of an excuse to go drinking around Europe than it was a rock’n’roll band.”

But Freeheat were still a good rock & roll band. Were you pleased with the results that you made musically?

JR: “Yeah, it was fun. I mean, if truth be told, I don’t know how seriously any of us took that band. It was more of something to do because there was nothing else to do at the time, if you know what I mean. But we were all into that music but at that time we were too soaked to the gills to get anything done.”

Did going dry remove you from the band element?

JR: “No, stopping drinking came much later on. Y’know, I’d moved outta London down to Devon and I had children and it just didn’t seem appropriate to be swigging away at a bottle of whisky at 10 o’clock in the morning and things like that.”

Did it really get that bad?

JR: “Well, yeah…it was that bad for me for years! I mean yeah, yeah…I drank all day every day for quite a long time. I was hugely overweight at one point; I was around 15 stone. But that was caused by long periods of doing nothing.”

Did you miss being away from music at that point?

JR: “Not really. It gets to the point where you think that you wouldn’t mind doing it again but I quite enjoyed my days of whisky and burgers; it wasn’t all bad.”

Do you miss the drinking days at all?

JR: “Oh yeah. In those days I didn’t have a care in the world. I’d just put on my shoes, go buy some drink and just get slaughtered but if you do that for too long it’ll just be the end of things.”

How hard has it been to resist temptation since the Mary Chain have reformed?

JR: “It’s pretty hard, I gotta be honest, it’s pretty hard. The hardest bit was that I’d never done a gig sober until the Mary Chain got back together and I wasn’t sure that I was going to able to do it and I did and it wasn’t as bad as I thought and I then thought, Christ, I wish I’d done this years ago! But the hardest bit is when you come off stage and you’re just sitting around and everybody’s just sitting around the dressing room drinking and you’re just craving a drink; that’s the hardest bit. I mean, at home, I don’t even think about drinking anymore but when you come off stage and into the dressing room I’m just gasping for a drink. With Coachella there was a lot of pressure and the [warm up] gig the night before was terrifying, actually. The warm gig actually did the job and all my nerves were sorted out at that gig and Coachella was kinda unreal, if you know what I mean. It was nine years since we’d been standing on a stage like that; it was almost like a dream and I was thinking, well how am I going to do this sober? But it went by like a dream.”

How did the reunion gig come about?

JR: “To be honest, it was the Coachella people who kept harping on at us. Y’know, we’d kinda thought about the idea of getting back together and a lot of people tried it over the years and a lot of it was that I wasn’t sure whether it would work with me and William and he was the same. We didn’t know if we could share the band again because it was pretty hideous towards the end when we broke up in ’98 and neither of us really wanted to go back to that. So we thought that if we are gonna do it again then it’ll have to be different, we can’t just go back to bickering over anything.”

How is it different now?

JR: “Well, I guess we’re a bit older, we’re more sensible and we realise now…I know exactly how to get on his nerves and he does me because we used to take some sort of perverse pleasure doing that but now you think, well what’s the fucking point? If I say this then I know there’ll be an explosion so let’s not say it and get on with the music?”

So can we expect new material?

JR: “There is new material and we’ve got an album in the pipeline that we’re in the middle of. We’ve recorded bits and pieces here and there but we’re getting there. We’ve always been quite slow workers and the very fact that William’s in LA and I’m in Devon doesn’t exactly help but we’ll get there in the end.”

Given the distance between you, how exactly does the song writing process work?

JR: “Well, it’s kinda always been William’s songs and my songs; very rarely have we actually sat down and written together but traditionally, he’s always been the main songwriter in the Mary Chain. He always was and always will be and if we do another album then it’ll probably be largely William’s songs with about four or five of mine.”

You say that you’re lazy as a band but the new box set shows that you were actually a massively prolific band. If you weren’t lazy, just how much stuff exactly would you be producing?

JR: “We were always good at working to a deadline. We always were lazy and we always will be but there was more pressure back then. Now we don’t even have a record deal. There’s no one saying you’ve got to have a record ready by the first of January or whatever but back then you’d have someone saying, ‘Look, you’re fucking up and we need a record’ and we’d put it off until the last possible moment and it was now or never and we’d get our shit together and get it done.”

Going back to the start of the box-set, the track ‘Up Too High’ is about as far away from the Mary Chain sound as you could imagine. It almost sounds like The Pastels.

JR: “That first demo isn’t really a Mary Chain song; that was William. That demo was around before the Mary Chain even existed. It was recorded about 1983 or something. We talked about recording that song but for some reason we never got round to it. I remember that we played it to [WEA boss] Rob Dickens just before we were going to record Psychocandy but we didn’t have any stuff to play him and I said, ‘We’ve got that tape of “Up Too High”, why don’t we play him that?’ And we took it round to his office and he was going ‘Yes! Yes! That’s a Top 10 hit!’ and then for fuck’s sake I can’t remember why we buried that song for all this time. Honest to God, we’ve spent our entire careers shooting ourselves in the foot! We’ve got the chairman of the company saying it’s a Top 10 hit and we bury the bloody thing. I think the only reason we didn’t record it was because we were thinking we couldn’t do the song any justice at the time because we were thinking of a big production like the Walker Brothers or something like that and at that time we didn’t know how to do that. I imagine at the time that’s why we decided not to do that one and sort of forgot about it.”

So how did you get from there to the trademark Mary Chain feedback sound?

JR: “At the time, I guess it was down to the kind of music we were listening to at the time. I’ve probably said it a million times but it’s the truth: at that time we were really into stuff like the Shangri-Las but we were also really into stuff like Einsturzende Neubauten and we thought just wouldn’t it be amazing if we had a band that had the melodies of the Shangri-Las but the production values of Einsturzende Neubauten and we thought we’ll become that band, we’ll do that! It was just an idea that we had. We felt pretty good about ‘Upside Down’ and we wanted it to grab people by the throat and it kinda succeeded. We wanted a record that attacked people, we didn’t want it to come out of the speakers or the radio and go unnoticed. It may be naïve, but I also remember [being surprised] that ‘You Trip Me Up’ never made it to Number 1. I was always trying to work out what I was gonna wear on Top Of The Pops but fucking hell, we never stood a chance.”

How isolated did mainstream rejection make you feel?

JR: “We felt as we didn’t fit in anywhere because we wanted to be mainstream and you couldn’t admit that in 1985. There was this kinda DIY, sorta Woolies sandals and big cardie brigade that thought that indie music should only sell about 25 copies and that you should only play to about 10 people in the basement of a pub. That seemed to be the way of indie music back then and we hated that. We wanted to take Psychocandy to football stadiums. It sounds nuts now but that was our intention so if you told anybody that…we just seemed to alienate everybody. The indie kids hated us and the mainstream had never heard of us because we’d never get played on the radio.”

Did you ever feel like giving up?

JR: “No, not then because we always felt that we’d break through eventually. We had such belief in what were doing that we thought, well it’s a bit frustrating that it’s not happening now.”

Your early gigs were characterised by short sets and violence. Was it your intention to create such terrifying environments?

JR: “The idea with the Mary Chain at the time was that we didn’t wanna be just another band; if you found yourself by accident standing in front of the Mary Chain one night we wanted to make sure that you were never gonna forget that. The idea of playing Psychocandy and the songs of that time for a period of an hour seemed like a plod at the time. Y’know, those songs were like explosions and they were like an assault on the audience. To us, the gig should be 20 minutes, maybe half an hour, period. Anymore than that it just seemed that the impact was lost. But we didn’t invent that – The Fire Engines gave us that idea; they used to play for 20 minutes and we thought, Fuck! What a great idea! We’ll do that too!”

Was the violence an uncalled-for by-product?

JR: “To be honest, it was nothing that we’d planned. It was unfortunate. We didn’t want anybody to get their heads kicked in at a Mary Chain show and I certainly didn’t wanna get my head kicked in but I did [get a kicking] on many an occasion. Usually by the security.”

In the light of Alan McGee’s Art As Terrorism press release in response to the North London Polytechnic riot gig, did you feel any anger towards him for stirring things up for subsequent gigs?

JR: “Nah…we kinda let him go off and do what he wanted. He thought he was Malcolm McLaren at the time and would say these things without even realising it. He’d quote McLaren outta the ‘…Rock’n’Roll Swindle’ and we’d just piss ourselves laughing! He’d be: ‘Jim! Jim! Rule Number 1: No playing rock’n’roll houses’ and we’d go, ‘But that’s outta the ‘Rock’n’Roll Swindle” and he’d go ‘Oh, is it? Oh…oh…OK’. But it was funny, do you know what I mean? He was into McLaren and we were into the Pistols but nobody took it that seriously.”

So you didn’t have that antagonistic relationship with him that The Pistols had with McClaren?

JR: “Nah…Malcolm and the Pistols hated each other but we got along fine with Alan until we didn’t need him any more, if you get my drift?”

How big a deal was it for the Mary Chain to get to go to America for the first time?

JR: “It was great cos we’re into American culture like the Velvet Underground and The Stooges and to go to places like New York City just blew my mind. We went there in March 1985 playing to a few hundred people and in January I’d just signed off the dole. For me, it was just unreal. For me, it was like living a fantasy.”

Part two tomorrow