Three weeks before the first cobblestones were thrown in the explosive student revolt in Paris, May 1968, Télévision Suisse Romande broadcast the image of French yé-yé chanteuse France Gall’s small unconscious body carried down the hatch of the Savoie, a paddle steamboat floating on a frosty, overcast Lake Geneva. A strange funeral procession followed her down: a top-hatted illusionist, two muscular dancers dressed in sparkly forest-green bodysuits and white furry gilets, a dour Napoleon lookalike, comic singer Henri Dès in a purple Nehru jacket and pantaloons, and five ballerinas in bejewelled go-go boots and pastel-coloured wigs. A minute later, Gall would be upright again, dancing in the film’s grand psychedelic finale – but, with intense social and political upheaval looming, her mock death would unknowingly mark the symbolic death of yé-yé, the playful bubblegum pop movement that made Gall, Françoise Hardy, Sylvie Vartan, Chantal Goya, Annie Philippe and so many others famous between 1962 and 1968.

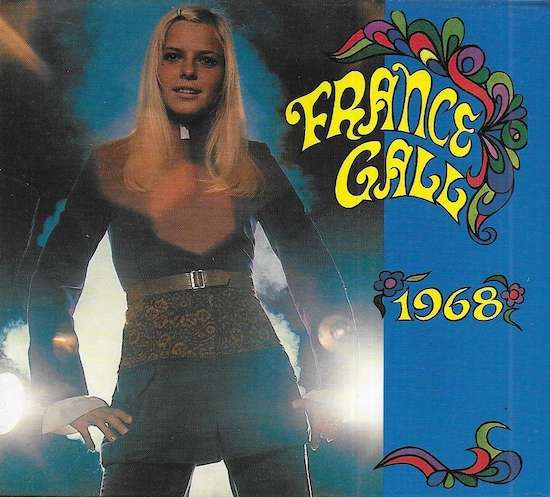

Gall’s mock funeral appeared in Gallantly, a 33-minute nautical caper promoting her seventh LP, 1968. Released in the first weeks of that year, the LP’s title and free-flowing flowery artwork seemed to promise 1968 would continue the carefree, loved-up hippy ideals of 1967 – and likewise the music within repeated many of the tropes of the Summer of Love sound: sitar-heavy exotica (‘Chanson Indienne’), chamber pop (‘Toi Que Je Veux’), North African slithering scales (‘Nefertiti’), hyperactive psych (‘Teenie Weenie Boppie’), cartoonish flute-led lounge jazz (‘Les Yeux Bleus’). Lyrically the LP is equally haphazard, taking in the perils of LSD, the pleasures of mini golf, Queen Nefertiti’s fragrant bandages, an insatiable flesh-eating giant, Anglo-Gallic dispute over the Channel Tunnel, the vicious love of a baby shark. While not wholly cohesive, 1968 is held together by Gall’s sweetly emphatic vocals: more than any other yé-yé singer, her sincerity and versatility enabled her to skip from genre to genre without ever tripping into parody or mawkishness. Throughout the mid 1960s, she was the embodiment of youthful optimism, consistently selling hundreds of thousands of records – but, by the time the stones and Molotov cocktails rained down on the Latin Quarter, she was no longer a fixture on French TV, her sales had slumped, her career seemingly irrelevant to this new, politicised youth.

Yé-yé was itself a potent youth-cultural revolution, exploding like a marshmallow cobblestone five years previously. The term ‘yé-yé’ was coined by sociologist Edgar Morin in a July 1963 Le Monde article, inspired by the opening ‘yé-yé-yé-yé’s of Françoise Hardy’s 1962 ‘La Fille Avec toi’, and singling out the movement’s more innocent, "festive, playful hedonism" in contrast to the aggressive, leather-jacketed machismo of the blousons noirs that had come before it. Morin’s article appeared shortly after 150,000 well-dressed youths had descended on Paris’s Place de la Nation for a raucous concert organised by radio station Europe 1, featuring yé-yé power couple Johnny Hallyday and Sylvie Vartan among many other Mod-suited, polka-dotted teen idols. French president Charles de Gaulle’s comments after the show – "These youngsters seem to have so much energy to spend. Let’s have them build roads!" – marked him as being complet…