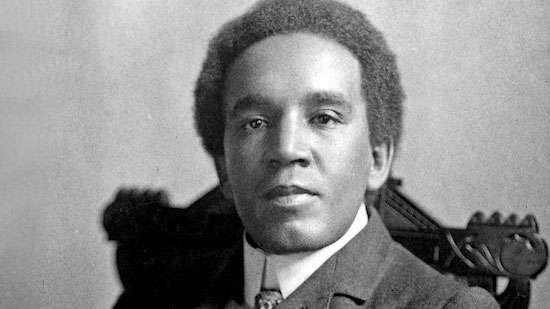

At the end of the 19th century, word was spreading in English music circles of an outstanding new talent – a composer in his early-20s called, a bit bizarrely, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (his mother had named him after the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge). His fans included Edward Elgar, who described him as “far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the young men”, and Arthur Sullivan of Gilbert and Sullivan. In November 1898, he told Coleridge-Taylor ahead of a concert at the Royal College of Music in London, “I’m always an ill man now, my boy, but I’m coming to hear your music tonight even if I have to be carried.”

Coleridge-Taylor was a recent graduate of the Royal College and he was returning on invitation of his old teacher to premiere an ambitious choral work, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. It was performed by students, who made a hash of it, but it caused a sensation nonetheless. Hubert Parry, writer of the song ‘Jerusalem’, later called the concert “one of the most remarkable events in modern English musical history”. In its aftermath, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast took off. It became wildly successful across Britain and then America, making a music star of the young composer as we recognise one today – a household name, critically and commercially lauded, and on both sides of the Atlantic to boot.

Elgar, already in his 40s, didn’t have a comparable success until the following year, when his Enigma Variations were premiered. Coleridge-Taylor’s former classmates at the Royal College, Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams, would have to wait much longer. And what makes this story of glory all the more exceptional is that Coleridge-Taylor had been born on Theobolds Road in Holborn, London – an expensive area these days, but not in the late-19th century. As the writer Mike Phillips points out in a biography for the British Library, it was just around the corner from the Fetter Lane slum, which Dickens described in Great Expectations as “the dingiest collection of shabby buildings ever squeezed together in a rank corner”. Coleridge-Taylor was also mixed-race. His father was from Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is no longer a household name, and it’s not exactly easy to work out why not. His story isn’t about the working-class composer of colour who was shut out and silenced by the musical establishment. Against the odds, he triumphed, and he became even more famous in the decades after his death in 1912, aged 37. Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast was the first in a trilogy of cantatas, The Song of Hiawatha, based on the epic poem of the same name by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In the 1920s and 1930s, season upon season of a ballet version of the full work was staged at the Royal Albert Hall, complete with an eye-popping 1,000 performers (choir, orchestra and dancers) and an enormous set in the round. This was an annual cultural event – an all-bells-and-whistles show for families of all classes – that punters would attend dressed as the Native American characters in the story. It was after World War II that Coleridge-Taylor’s name and music slipped away. By coincidence, he was very recently featured in a new BBC series on the last 100 years of British classical music, Our Classical Century, only for presenter Lenny Henry to ask the same questions I’m asking here: “Why didn’t I know about this guy? Why has he become forgotten?”

It might be that Hiawatha became an albatross around Coleridge-Taylor’s neck. He was good with music, bad with money, and he famously sold the rights to its popular first part for a lump sum of 15 guineas (it would go on to sell hundreds of thousands of copies). Because of that, he’s often been written about as having a career arc similar to a one-hit wonder in the pop business today: needing to make a living, he tried to follow up Hiawatha with another big hit, failed, released too much easy-win ‘light music’, fell out of favour, and drove himself to an early grave by working too hard, not just as a composer, but as a teacher at the Trinity College of Music in London, and a conductor of provincial orchestras.

If there’s any truth to that – and I think there is – it’s a tragic story, but it isn’t the only way to look at Coleridge-Taylor’s life. In recent years, musicians searching for a piece to record that’s off standard repertoire have been looking beyond his salon music and finding pearls – particularly his Violin Concerto in G minor, which he wrote in his final year. It wasn’t recorded until the 2000s and it’s now considered to be a classic, forcing something of a reassessment of Coleridge-Taylor’s musical reputation. And there have also been discoveries of major works once thought to be lost, including his only large-scale opera, Thelma, written between 1907 and 1909. A PhD student researching Coleridge-Taylor unearthed the original manuscript in the British Library and it received a long-overdue world premiere in 2012, exactly 100 years after his death.

We understand Coleridge-Taylor better now as a composer than at any point since he died, but there’s yet another way to consider his story and it’s perhaps the most astonishing of all. He visited America three times in his life and published music in the country that was probably never sold in Britain, like his 24 Negro Melodies – piano arrangements of spirituals. Those works made him a cultural icon to African-Americans in the proto-civil rights era and offered him a legacy in the States that’s markedly at odds with his one here. In 2012, a documentary called Samuel Coleridge Taylor And His Music In America, 1900–1912 was released and it’s genuinely revealing. This Anglo-African composer, who’s barely a part of any conversation in Britain in the 21st century, remains a figure of great historical importance in America, a country which – by birth, at least – he had no connection to at all.

The upbringing of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is knotty and it’s only recently been unpicked by his biographer Jeffrey Green in a 2011 book, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, A Musical Life. We know that he was born in 1875 to a white English mother, Alice Martin, and a black Sierra Leonean father, Daniel Taylor, a medical student at King’s College, London. They probably weren’t married and it’s likely that Daniel never knew that his 18-year-old girlfriend was pregnant. He returned to Africa before his son’s birth to work as a coroner for the British Empire in Senegambia.

It was a squeeze at the house that Coleridge-Taylor spent his very early days in – 15 Theobolds Road. It’s thought that Alice was the illegitimate daughter of a blacksmith called Benjamin Holmans Sr. and she was living with him and his family (her own mother was in Kent) at the time her son was born. A census shows that two other families inhabited the same house, until it was demolished when Coleridge-Taylor was 18-months-old. His mother moved him to the relative security of suburban Croydon, where she married a railway worker, George Evans, and had three more children. Coleridge-Taylor never left Croydon and he’s absolutely one of the town’s many musical heroes, alongside Ralph McTell, Kirsty MacColl, Saint Etienne, Stormzy and Skream.

Jeffrey Green believes that Coleridge-Taylor’s talent was inherited from his mother’s side – the Holmans, who were a musical family. Benjamin Holmans Sr., an amateur violinist, gave his young grandson violin lessons, then paid for professional instruction when it became clear he was a prodigy. Supported by both his family and local members of the music community in Croydon, Coleridge-Taylor applied for a scholarship to the Royal College of Music when he was just 15. He got in as violin student, then switched to composition.

Coleridge-Taylor suffered appalling racism at school. He was nicknamed ‘coaley’ and once had his hair set on fire. The story – as told within the cosy confines of the classical world – is that music saved him, although it isn’t true. His professor at the Royal College, Charles Stanford, was once forced to silence an abuser by saying that Coleridge-Taylor had “more music in his little finger” than the other student had in “his whole body”, and there’s evidence that he was the victim of further racist attacks throughout his life. In 1899, he married a fellow student at the Royal College, Jessie Walmisley, and they had two children. Long after he died, his daughter Avril – an acclaimed pianist, conductor and composer in her own right – wrote that there was a group of youths in Croydon who would continually make comments about the colour of his skin, and, “When he saw them approaching along the street he held my hand more tightly, gripping it until it almost hurt.”

In his biography for the British Library, Mike Phillips says, “It takes no great imagination to see in Hiawatha’s Wedding a substitute for African-American experience,” and it’s fascinating to trace the racial awakening in Coleridge-Taylor’s life and work. Two figures are key: the African-American poet Paul Dunbar and Frederick J. Loudin, leader of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an a cappella ensemble made up of students at Fisk University, a black college in Nashville. When Coleridge-Taylor was 21, he heard that Dunbar was in London, so he sought him out and they collaborated on a number of early, pre-Hiawatha works that I don’t think have ever been recorded – Seven African Romances, A Corn Song and Dream Lovers. It was also in London that Coleridge-Taylor heard the Jubilee Singers. He befriended Loudin and wrote in the foreword to his 24 Negro Melodies that it was through Loudin that he “first learned to appreciate the beautiful folk music of my race”.

In England, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast was hailed as a great choral masterpiece in a tradition stretching back to Handel’s Messiah. In America, it took on a more socio-political bent and was held up by African-American leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington as an example of what an artist of African origin could achieve. Coleridge-Taylor met them both and it was Washington, then the most famous black man in America, who wrote the preface for 24 Negro Melodies, published in 1905: “It is especially gratifying that at this time when interest in the plantation song seems to be dying out with the generation that gave them birth, when the negro song is in too many minds associated with rag music and the more reprehensible ‘coon’ song, that the most cultivated musician of his race – a man of the highest aesthetic ideal – should seek to give performance of the folk songs of his people by giving them a new interpretation and an added dignity.”

In the late-19th century, composers across Europe were looking to folk traditions for inspiration. With 24 Negro Melodies, Coleridge-Taylor was doing something similar. He would have known that one of his music heroes, Anton Dvořák, had visited America before him and declared “the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called negro melodies”. His arrangements were a response. “What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvořák for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro melodies,” he said. The results are stunning and they have been recorded, including in 1979 by Frances Walker, sister of the composer George, who I covered in a previous column and died earlier this year. Her album was made in

one take at home in New York, giving them a warm, intimate and personal feel. “When I play the pieces, I’m not thinking what Coleridge-Taylor is thinking,” she said in 2012, “I’m just playing what I think is beautiful music. But I know where it’s coming from – it’s describing suffering, and happiness, and instances when slaves suffered.”

Coleridge-Taylor visited America in 1904, 1906 and 1910, on invitation of a society set up in his name. “Once he got here,” reported The New York Times when he arrived on his first trip, “the most eminent musical people of Washington turned out to honor him – as a composer, an eminent composer, not a negro composer.” He was invited to meet – one-on-one – President Roosevelt at the White House, and he attended a concert of his works. “The musical critics of the Washington papers, mostly Southerners, conceded that the chorus of negroes was one the best managed, best drilled, and most successful choruses that had ever appeared in Washington,” the Times added. “The one weak point in the performance, according to the critics, was the orchestra. And the orchestra, alone of the component parts of the festival, was made up of white men.”

On a later visit, he became the first musician of colour to conduct an all-white orchestra, giving him the nickname ‘African Mahler’ (his music sounds nothing like Mahler’s, but Mahler was as famous at the time for conducting as composing) and he left such an impression in America that two schools have been named after him – in Louisville, Kentucky and Baltimore, Maryland. In Britain, there are none, although there is a youth centre in Croydon bearing his name. It’s not enough. Each year he’s discussed during Black History Month, then ignored again. He should be thought of a composer who isn’t lost, but ripe to be explored. More of his works need to be recorded and, as Stuart Jeffries wrote in The Guardian in 2003, “If they can rename Liverpool Airport after John Lennon and call a Parisian street after a black musician and revolutionary, why not name West Croydon station after Samuel Coleridge-Taylor? Commuters could stand on the platform and, during the long wait for delayed trains, think about what might have been had he not died so young.”

It was on a platform at West Croydon station that Coleridge-Taylor collapsed in 1912, suffering from exhaustion and pneumonia. He made it home and was reported to have been conducting his recently completed Violin Concerto to himself, in a delirious state, right before he died. He wasn’t broke, but he wasn’t wealthy either. A memorial concert was held at the Royal Albert Hall to raise funds for his family, arranged by musicians who were stunned to learn that he’d signed away the rights to Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. A scandal ensued and it led to Coleridge-Taylor making one final gift to music, from his grave – the case led to the formation of the Performing Rights Society (PRS) in 1914, meaning that all musicians who came after him would be properly paid.