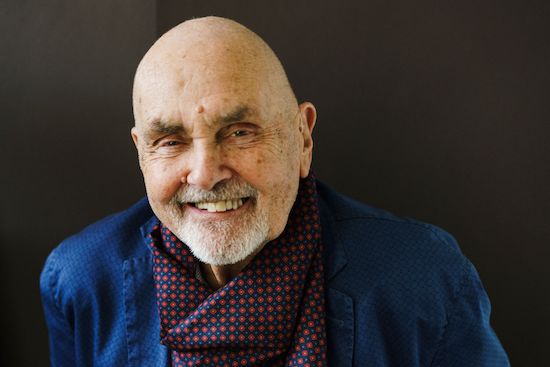

“I have a good memory. I think everything from the beginning of my childhood until now is somehow predestinated – cantors and preachers, art, making music. My life’s project started a very long time ago indeed – perhaps since Adam and Eve.”

Hans-Joachim Roedelius is surely among the oldest surviving practitioners in rock/post rock and, still more remarkably, still producing work of vitality and contemporary relevance. He was born a few months before Elvis Presley, in 1934 and, before his relatively late start in music lived a varied and extraordinary life, buffeted by the rise and fall of the Nazis and the postwar cleaving of Germany. As a child, in the pre-war Nazi era, he appeared in popular films. During the war, he found solace and refuge in East Prussia, striking up an affinity with nature that would be lifelong. After the war, he found himself in East Germany, arrested by the Stasi as a supposed spy before making it back to West Germany just in time, before the Wall went up. He took a variety of jobs, including gardening, nursing before becoming a masseur.

“I worked a long time as a beauty therapist,” says Roedelius. “It’s a hard job listening to customers every day, listening to their stories. These were people of all kinds, everything from politicians to wine merchants, every kind of social circle. I worked with old ladies in their beds, first thing in the morning. I was really able to connect with them, I had a gift for it. So I worked first as a therapist, then as a therapist through music.”

A turning point in his life came when he met Conrad Schnitzler, the great outsider artist, sonic brutalist and incorrigible maverick, with whom he would go on in 1968 to found the Zodiak Free Arts Lab in West Berlin, one of the cradles of Krautrock, in which he became involved in various noisenik happenings and loose free Improv collectives. “Conrad took care of me when I went over from East Germany to West Germany. I really appreciated the care he took of me, made me part of his family. He taught me a lot; so much so, that without Conrad Schnitzler, I would not be where I am today. He was also quite a strange person. He left the Arts Lab shortly after its inauguration to work on other projects and yet it was he who invented it. He invented Kluster with a K, a whole stream of music with his power, energy and talent.”

When the Zodiak Free Arts Lab shut after just a few months, Roedelius would team up with Schnitzler and Moebius to form Kluster, later (minus Schnitzler) Cluster who would evolve from untutored but inspired purveyors of abstract, industrial noise into a gentler but no less radical proposition. Throughout the 70s they created first drafts of a putative new mode of pop, based on deceptively unassuming loops and evocative use of the new electronic palette. Brian Eno, whose thoughts were turning in a similar direction post-Roxy Music, sought them out in West Germany and they would record a number of albums together, like minds in tandem, including Cluster & Eno and, with Harmonia, Tracks And Traces, recorded in 1976 but only released in Krautrock’s lengthy, posthumous golden era in 1997.

“Brian Eno was a great help on our way. When he came over to meet us, to work with the already-split Harmonia it was very much according to the Cluster principle – playing music in the moment, with no overdubbing. It was great to see him play as part of this four-man group. Because it was recorded on a four track machine, no-one thought it could be a record afterwards. It needed 20 years to bring it to the market. But it’s a very important milestone in all our careers.”

A devout Catholic, Roedelius reminds of the Dada leader Hugo Ball in some ways, a man who eventually decided he could no longer “bid chaos welcome”. With Cluster and over countless solo albums and collaborations, he has pursued a music which Julian Cope aptly described as expressing a “raging peace” – a tranquility borne out of a full knowledge that the world is desperately un-tranquil.

“I think I come out of the great German Romantic tradition. It’s part of my inner experience. Beauty, optimism, hope – I can’t save this crazy world but I do want to bring to this world some peace, some release from the constant strain, especially in times like these which can feel really, really hopeless. Artists are responsible for the health of the world. Brexit!” he exclaims, in despair at Britain’s present pass. “That is such a horrible idea. How crazy to get rid of Europe.”

Perhaps if there is a secret to Roedelius’ longevity it is that he is constantly busy, looking ahead, never permitting himself to rest on the laurels of retrospection. His latest work, Imagori II, a second collaboration with Christoph Mueller, is out this month.

“I have very little time to listen back to my old work, I am too busy doing what I am doing in the present – film music, running a festival. I feel very glad – the old catalogue has been reissued and we are getting a newer, younger audience. The audiences I played to last time in America were young, not old. It makes me glad I always stuck to my beliefs. But I have no choice – I have to do what I do.”

Human Being – Live At The Zodiak, Berlin 1968 [2009]

This is one of the few surviving excerpts of soundmaking at the Zodiac Free Arts Lab, founded by Roedelius, Conrad Schnitzler and Boris Schaak in late 1968. Arising from a commune of the same name, it’s an extended, hour-long piece of outsider improvisation featuring tolling percussion, chants, muffled, industrial drones and dolorous peals of brass. It is part of the prehistory of Krautrock, a new mode of music slowly emerging from the waters onto land. “We were all non-musicians,” recalls Roedelius of those days. None of us knew how to structure or compose. You could say we were music action-ists. We had to do all that we were able to do to see if it worked or not. And after a while, it did work.”

Kluster – Klopfzeichen [1970]

Recorded with the discreet assistance of Conny Plank, Klopzeichen (“Knocking signals”) was the debut album by Kluster in their harsh “K” stage. It features one Christina Runge sternly reading out an extremist manifesto of sorts, opting ominously out of modern West German society; this is set against a remorseless backdrop of ghostly, clanking rattle and reverb created by Roedelius, Dieter Moebius and Conrad Schnitzler, rendered vivid by the sympathetic Plank. Roedelius said he “hoped it might have opened the doors to a new understanding of how to live”. In its time, its proto-industrial/dark ambient terrors would have troubled the ears of only a very West Germans; it stands today as a neglected, monumental proposition to transform society through art and music, rather than bombs.

Cluster – Cluster’71 [1971]

The debut album for ‘soft C’ Cluster, following the departure of Conrad Schnitzler, this is still a record that sounds half a century ahead of its time in its compelling use of abstraction, reverb and repetition, applying the strategies of postwar modern visual art across the full, 44 minute range of an album canvas. Producer Conny Plank enjoys the rare but deserved honour of being credited as a musician on these three untitled tracks, in which guitars, cellos and organs played by Moebius and Roedelius dissolve in an acid bath of electronics. It’s a record that takes off where Hendrix’s ‘Moon, Turn The Tides . . . Gently Gently Away’ leaves off, exploring deeper fathoms, leaving conventional rock instrumentation still further behind. For those only familiar with the more pastoral tones of later Cluster, this album is a retrospective revelation, a thing of terrible beauty.

Cluster – Zuckerzeit [1974]

This was the first Cluster album of the duo’s more pacific era but despite its pop tones it is as exhilarating in its own way as their early, noisenik fare, as well as more palatable to wider audiences. Its miniatures remind of the sort of work Eno was doing at this time, with familiar knocking, nautical percussive effects on ‘Hollywood’ and the sort of reverb chatter with which Eno trails off on the final track of Roxy’s For Your Pleasure. This is the sort work for which Roedelius would become best known – rough studio drafts for future pop Utopias. “When Moebius and I played more together, the more we approached harmonic fields,” says Roedelius. “It had to happen, this return to melody, to get back to what I always saw as my romantic predestination.”

Harmonia – Musik Von Harmonia [1974]

When it came to his contemporaries, Roedelius was not always acutely conscious of their work, being immersed in his own. “I was aware of the way other experimental German groups worked,” he says, “but we had little time, we had to work and live in the forest, do gardening – so I didn’t really hear their music. I was never a fan of ‘designed’ music like Kraftwerk. I lived in Düsseldorf for a while and knew Florian Schneider’s sister but I was not really a fan of what they did.” One Düsseldorf artist he did appreciate, however, was Neu!’s Michael Rother, whose way of working chimed in with Cluster’s own, more organic approach. He added his own guitar layer of reverberant shimmer to a three-way mix on Musik Von Harmonia, recorded during 1973 and released in 1974. There is humour, in the album’s splashy cover, a spoof on the activities of Düsseldorf’s advertising agencies and in punning titles like ‘Sehr Kosmische’, (Komisch/Kosmische, geddit?), a track which slowly and painstakingly clambers and put-puts its way to the stars.

Cluster & Eno – Cluster & Eno [1977]

There are Eno-esque elements in Cluster and Cluster-esque elements in Eno but it is hard to determine who was the greater influence on the other. Suffice it to say that in his visual arts-style approach to applying sound and understanding of the studio Eno was an “honorary Krautrocker”, visionary in his understanding of what his West German contemporaries were trying to do – he had dubbed Harmonia “the most important band in the world” and when working with them, and Cluster alone, cheerfully fell in with their manner of recording, under the aegis of Conny Plank; he is but one of three constituent parts of this album of pop, Ambient, watercolour – or four, if you include Plank himself. “Brian wrote that working with us was like being in a bubble – it was a strange development for him,” says Roedelius. “He was working so differently from how he normally works on Cluster & Eno. He brought us to a bigger audience; then we worked on ‘By This River’ on Before And After Science (1977). We were able to live for two or three years just off this one piece. I always loved his work.”

Roedelius – Selbstportrait I&II [1980]

Comprising recordings made between 1973 and 1977, Selbstportrait is an album that perhaps closest epitomises Roedelius’s romantic quest for artistic self-realisation or “perfect autobiography” realised in sound. Its grainy, keyboard sound sketches may sound tentative, unfinished, minimal but, as with Boards Of Canada they represent indistinct, intimations of a submerged past, lost, dormant worlds only discernible through the power of musical recollection. This is far more evocative than a more polished, full-blown set could ever hope to be. “I still try to keep my Romanticism alive,” says Roedelius, “to keep my thinking positive, to keep the soul alive, to utilise the brain. That is my predestination.”

Roedelius – Wie Das Wispern Des Windes [1986]

Unavailable on CD for years before it was reissued by Bureau B, Wie Das Wispern Des Windes (Like the whispering of the wind) indicates that over the years Roedelius developed a facility for playing on the acoustic piano (in this case, a 19th century Bösendorfer). These Farfisa-free pieces are full of colour, shade and tinkling nuance, qualities which underpin his electronic work also. There are elements of Satie in the limpid minimalism of these pieces, which are more than mere descriptions of nature; through gentle repetition, they amount overall to a Romantic meditation, whose centrepiece is the ten-minute-long ‘Raindrops’.

Cluster Qua [2009]

This would turn out to be the final album in which Roedelius teamed up with the late Dieter Moebius and proved to be a fitting finale for two talents undimmed by age and enhanced by new studio possibilities. Titles such as ‘Zircusile’ and ‘Putoil’ echo Autechre, word-like shapes stressed the essentially abstract nature of music, and this music in particular. It’s an inescapably beautiful listen, however, gentle and harmonic despite the garrulous layers of activity – throbbing basslines, liquid eruptions, skittering synths and busy, tropical landscapes, as if they have arrived at last in the electro-xotic land they promised in the 1970s, alone among the teeming wildlife and foliage. “Our final album together, Qua, I feel has not properly been appreciated as a proper piece of tone art,” says Roedelius.

Mueller Roedelius – Imagori II [2018]

Christoph Mueller and Roedelius first recorded together in 2015 for Imagori, though on that occasion they simply swapped sound files over the internet. For this follow-up, they were able to work in the studio, a far preferable arrangement. “Christoph’s background is in tango – he is mastermind of the Gotan Project,” says Roedelius. ‘I have always needed someone like this, like Conny Plank, to produce me because I am not a producer at all. Even with my solo works I have required technical assistance.” Imagori II is an album of creative contrasts; between language and music, between the choppy, contemporary beatscapes of Mueller and the ancient, futuristic glades and vales of Roedelius. It’s further testimony to the capacity’s Roedelius’s tirelessness and immunity from the effects of age on the truly creative soul.

Imagori II is out now on Gronland