About five years ago, I travelled from Liverpool to Cardiff Castle to see the Manic Street Preachers perform the showpiece leg of their The Holy Bible anniversary tour. They played their crushing third album in full, followed by a selection of ‘greatest hits’, starting with ‘The Everlasting’, the opening track from the album that has gone down as their populist peak, This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours. There were more tracks from the same album in the second half than from any other, perhaps a marked attempt to raise the tone from the opacity of The Holy Bible to that anthemic, grand-occasion pomp that their later work possesses.

Imperious as The Holy Bible is, in the grounds of a beautiful castle on a sunny day, with ‘Manic Street Pizzas’ (‘Margherita Emptiness’, ‘Everything Must Goat’s Cheese’, ‘Tsalami’, etc.) on sale in the food court, the greatest hits show was better. There are many different sides to the Manic Street Preachers, and to an audience of thousands on a summer’s day, it is the ‘mainstream’ side, the anthems and the singalongs that are the most successful.

After the show, I came across a thread in one of the Manics’ many fan forums that saw one irate fan, of the feather boa and leopard print brigade, who had been on the barrier for the Holy Bible set, complaining about the clash with the boorish lagers-in-the-air louts that suddenly barged their way into the middle for a pogo and a singalong once the ‘hits’ finally got their airing. It highlights a strange divide of sorts within some corners of the Manics fanbase, an idea that the manner in which the band consolidated their position as Britain’s biggest band with This Is My Truth saw them blunting themselves, betraying what they once represented.

At the close of 1998, Melody Maker ran a debate feature asking whether the Manics had ‘sold out’, a discussion that had been raging since the record’s September release. They cited fans furious at James Dean Bradfield for duetting with Sophie Ellis Bextor on the superb The Everlasting EP track ‘Black Holes For The Young’ (“Richey would never have let this happen,” said one fan) and for seemingly retreating into middle age: “They’ve lost all their rock star aspirations, passion and energy. They’re just too nice, like Barry Manilow or The Bee Gees.” It was a time where the band’s music was being used to soundtrack commercials for the Welsh tourist board, and for instrumental links on sports channels.

MM’s Daniel Booth summed up the root of this revolt: “According to their detractors, the explosive insurgence of old – meaning both the punk militancy of ‘Faster’ and the anthemic sweep of ‘A Design For Life’ – has been substituted for something less immediate and more mellow, plagued by over-elaborate production. What is indisputable is that their music has become gradually more accessible.”

It has now been twenty years since This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours was released. In that time it sold over five-million copies, spent 74 weeks in the UK charts, and won best band, best album, best live act, best single and best video at the NME Awards, and best British album and best British group at the BRIT Awards. As Sarah Zupko, writing in Pitchfork in 1998 put it, the Manics were “Now beloved throughout the U.K. as the ‘nation’s band,’ – Oasis having lost the plot and forsaken that role with Be Here Now – they are very much of the musical establishment.”

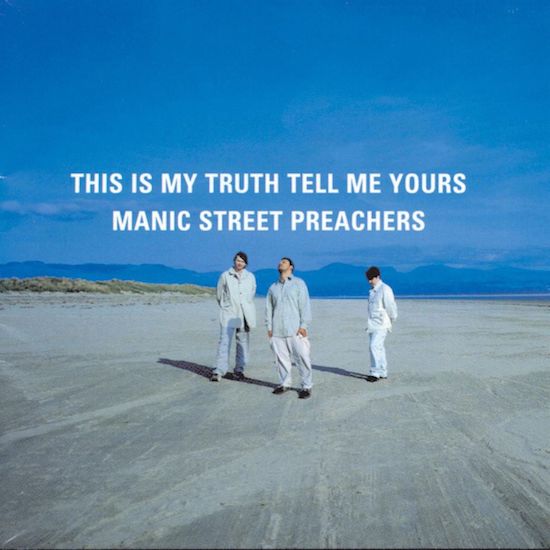

It is easy to see why the band’s original fans, first attracted by the group’s outsider status, wilful disregard for the zeitgeist and ostentatious sloganeering, were repelled by this new, streamlined band, their lyrics now written entirely by Nicky Wire and without Richey Edwards for the first time. They sounded slick, polished and poppy, were playing songs like ‘You Stole The Sun From My Heart’, with its chorus clinically targeted at making a stadium’s worth of fans jump around, and looked positively bland in comparison to their gaudy and glamorous former selves in the plain, baggy white that they wore on its cover. Yet to dismiss This Is My Truth on these terms, as many have done and continue to do is not only to do it a disservice, but to overlook what is in fact the most powerful statement the Manics ever made.

Most obviously, there is the record’s megahit lead single, ‘If You Tolerate This Then Your Children Will Be Next’, which sold 156,000 copies within a week to become their first number one. Looking back, its lyrics, inspired by the Spanish Civil War, are prescient. A line like, "If I can shoot rabbits then I can shoot fascists" resonates in a time where the relative merits of literally punching the alt-right in the face are subject for debate. It is a tremendous single, sad but not self-loathing, sweeping but entirely un-bombastic, and boasts some of the most stirring lyrics Wire has ever written without slipping into the sixth-form poetry he’s been guilty of on occasion. There aren’t many better opening lines to a number one single than, "The future teaches you to be alone, the present to be afraid and cold."

Yet the Manics have many tremendous singles, many of which had a political bent. There is the strident anti-capitalist statement of ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’ and the class war rallying cry of ‘A Design For Life’ for example. Taken entirely on its own ‘If You Tolerate This’ is no different as a statement lead single that slips uncompromising politics beneath a populist gloss, but its extra significance comes with a look at the wider context.

In a recent interview with NME in which he briefly looked back at the song, Wire noted that the band already considered the album ‘in the bag’ while they were working on it, safe in the knowledge that the already-written ‘Tsunami’, ‘You Stole The Sun’ and ‘The Everlasting’ were sure-fire hits, and initially considered ‘Tolerate’ worthy of being a B-side. That they changed their mind and decided not only to include it on the record but release it as the lead single is what’s notable. The band had commercial domination more-or-less assured, and musically ‘You Stole The Sun’ was a far more natural fit to consolidate it, but by choosing ‘Tolerate’ they made a statement – “using the past to illustrate what’s missing from the present,” as Wire puts it.

A grand political statement single such as this had particular significance in 1998 too. It was a politically optimistic year of a pre-Iraq Tony Blair with the charts dominated by the likes of Steps, Boyzone, M People, Robbie Williams and the Titanic soundtrack. The Manics often moved intentionally against the zeitgeist, but this time it was different. Unlike, for example, the battering ram approach of releasing a pompous glam-rock double album during the height of baggy – as they did with Generation Terrorists – with This Is My Truth they were more subtle, measured and intelligent, working from within by appropriating just enough of 1998’s gloss to make it palatable for the masses, but keeping their edges as sharp as ever. Look at the video for ‘If You Tolerate This’, for example, which takes full advantage of its late-90s budget with sleek, appealing special effects, but also begins and ends with a music-box version of socialist anthem ‘The Internationale’.

There is also, obviously, the album’s title to consider. “This is my truth, tell me yours” are the words of Aneurin Bevan, the Welshman who effectively created the NHS and was a socialist thorn in the side of the establishment for his lifetime. Appropriating quotes is nothing new for the Manics – great phrases litter their releases, setlists, merchandise and lyrics – but never before or since have they named an entire album in this way. The working title was simply Manic Street Preachers, but again the band reconsidered. The album would have sold just as well without its unwieldy title, but they included it nonetheless.

This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours also contains, buried at its very end, ‘South Yorkshire Mass Murderer’. It gets little attention in retrospectives of their work, but is one of their most uncompromisingly confrontational moments, a scathing attack on the authorities who blamed the Hillsborough disaster on the Liverpool FC fans who were crushed to death. “How can you sleep at night?” asks James Dean Bradfield, over and over again with stark, brutal clarity. Here there are none of the bells and whistles of the Manics’ sloganeering past, only viciousness and pitiless rage. This was long, long before the Hillsborough families actually received any justice, a time when they were still vilified and demonised by many. Closing a triple-platinum-selling album with a song like this was not a light decision. When I interviewed Nicky Wire earlier this year, we touched on the track in relation to its ‘companion piece’ ‘Liverpool Revisited’ on their latest record Resistance Is Futile: “When we wrote ‘South Yorkshire Mass Murderer’ we got a lot of shit from people saying, ‘You shouldn’t write shit like that!’ because even by then, no one believed [the Hillsborough families]. To fight hard and take on every fucker, it’s such a symbol of old school working class solidarity of the most exceptional kind.”

Of course not all of This Is My Truth is as political. As Zupko’s Pitchfork review of the time says: “Essentially, Wire paints with much smaller brushes, focusing on self, relationships and family while penning the Manics’ most emotional and personal set of lyrics ever.” But crucially, as she continues, “the personal is still informed by the political.” There are many moments of reflection and introspection, but peppered amongst them are political statements as grand and wide-reaching as the Manics have ever made.

An album like Generation Terrorists might have more political lyrics, a scattergun attack of slogans and statements, but it is not nearly as articulate in its statement as This Is My Truth. Conversely, a record like The Holy Bible might boast superior songwriting and a singular vision by the great Richey Edwards, but it was too dark, complex and anti-commercial to offer much hope of spreading its message all that far. Everything Must Go – the Manics’ first stab at mainstream appeal – is far rawer emotionally and less refined, while the Manics’ post-TIMT records were released to a public that would never again care quite this much about what the band had to say.

Though This Is My Truth remains derided by a number of Manics fans to this day as the moment they first detached from what made them great, to dismiss it as any form of ‘selling out’ is to fail to look beyond its glossy outer layer. Between the anthemic choruses lies the most coherent political statement the Manics made, to the largest audience they would ever reach.