"I don’t really see myself as a narrator, more like a mouth at the end of a broken antenna."

An antenna that’s slightly twisted and mischievous, receptive to impulses from everyday life. Laurent Gérard is a 21st century chanteur, an electronic bard, who freely shapeshifts from the world of online standup comedy to experimental art and music, often critiquing the hand that feeds him.

In a way, Gérard is a rare species in today’s underground music world: he doesn’t take himself too seriously, but remains serious about his art. Melody and sonic experimentation blend in his existential lyrical songs, be it the solo project Èlg, psychotropic duo Opera Mort (with Jo Tanz), Orgue Agnes (with the members of Kaumwald, Sourdure and Clément Vercelletto), trio Reines d’Angleterre (with Jo Tanz and Ghédalia Tazartes) and the hilariously demented duo Schultz and Elg with sound poet Damien Schultz.

His latest album Vu du Dome (Seen From The Dome) was released by Editions Gravats in April this year. On his new album, he oscillates somewhere between macabre, codeinated chanson, Coil, Nurse With Wound and Mordant Music.

Your new album is called Vu du dome (Seen From the Dome) – the first track incorporates bells. Is there a spiritual or religious theme that you wanted to explore?

Laurent Gérard: If by spiritual you mean the search for the big trip, the big journey from A to the far Z, then yes. I used bells, amongst other sounds to create a nebulous sensation of floating or elevation but they are detuned, melted, they’re "impure". Like getting high and sinking at the same time, air and water in the same movement and that sensation is spiritual to me. Sometimes there is meaning and sometimes, I just use sounds and words I like the ring of. The word "Dome" has multiple meanings and I find it very inspiring both symbolically and architecturally.

There seems to be a narrative to the tracks – micro-stories with snapshots of dialogues, gradation, suspense. As if you were a narrator recounting stories through music.

LG: Sure, every track is like a closeup in a fresque, each telling different stories. I don’t really see myself as a narrator, more like a mouth at the end of a broken antenna.

Can you elaborate some of these stories? Are they biographical?

LG: As some of the vocals are not related to any language, they got a story line at the very moment I gave them a title: ‘Au bûcher’ (meaning “at the stake”), ‘La véritable genèse’ (meaning “the real genesis”) or ‘Soeurs de crin’ (meaning “horsehair sisters”). I open a world of possible narratives with just a bunch of words affixed to the sounds.

Other tracks, like ‘Hourra’ or ‘Maisondieu’, are based on fragments of the French language. Like a deconstructed memory. Like Robocop recounting some parts of his history. It’s blurry and melancholic on the one hand and very free on the other because you can shape your own poetic idea of the song with this disposable cut-up.

What importance does language and its deconstruction play in your music?

LG: I enjoy language when it is electrocuted, buried alive, scattered and transformed. Daydreaming in alien babble. What is it? A prayer? A call for lunch? A bad joke? Someone vanishing in a puddle? When language is not immediately recognisable then all stories are possible. In the song ‘Panorama’ though, I sing in French and I am clearly describing scenes in a mall. It’s super banal. People picking up goods from the shelves and sad indoor plants. It’s totally basic songwriting, just a description, no commentary. The long silences between the words make it awkward and extremely melancholic to me. ‘Un filtre en or’ is similar. Catherine Hershey, who sings with me on the track, sees us as androids in golden bikinis selling vacuum cleaners and happiness on a home shopping network.

Can you talk about your songwriting process?

LG: Most of the time I discover that what I thought was the point of arrival was actually only the point of departure. I spend weeks on a song or whatever piece of music. Weeks of digging, borderline discouraged. Once I let it go and have a look at this thing through a different angle, I realise that only a tiny fragment of what I’ve done until then is actually the core of the piece I’m looking for and that’s when I crack the code to find the rest of the composition. Most of the time I have to remove things instead of adding layers. Other times I go straight to the point like with the song ‘Au bûcher’, two glasses of wine, one take, one overdub and just two points of editing. With the song ‘Ce sérum monstre’ I had this weird vaguely hip hop loop and only the three words “aucun clone municipal” meaning “not a single municipal clone” and the sentence fragment “ne budgeterait l’air” meaning “would budget the air”. It quickly opened a whole world in my mind bringing together city councillors, whales and shadow budgets. I recorded the song in a hysterical state, feeling as though I were in the skin of a schizophrenic prophet yelling into people’s faces in a city park.

How do you as an artist perceive time, the thought processes related to a project and its temporal aspects in relation to your work, especially nowadays, when time is a scarce and capitalised commodity? Stockhausen, for instance, worked several years on pieces lasting a few minutes.

LG: When I work with a label there are often more or less definite deadlines for record releases etc., but because these are independent labels (like Editions Gravats) there isn’t any pressure. I like knowing I have two years to record an album and then taking my time within that time. I find it stimulating. Experimenting with time perception is something I’m really into musically. It’s something I perceive from a cinematic point of view. Trying to condense a movie’s worth of experiences in a three minute song (‘Hourra’ on Vu du Dome). Or stretching out a simple snapshot into a 10 minute opus (first quarter of ‘Mauve Zone’). As a listener I love when a composition takes me for a ride on the great time accordion and I lose my grip on reality. Luciano Cilio, Joseph Hammer, Eliane Radigue and more recent bands like Société Etrange or the cosmic singer songwriter Eric Chenaux create that space for me.

How do you deal with distraction while you are working, especially since you are involved in so many projects?

LG: Some distraction is positive. Some digressions, some spatial and temporal leaps from YouTube cats playing piano to surreal Japanese pornography can be inspiring. Others can make you feel bad and then I do my best to recognise these spirals of alienations by transforming them into music or comedy or both.

Your work employs images, imagery, symbolism, it’s poetic and cinematic. Aside from your solo output, you also have a duo called Opera Mort. Can you talk about it?

LG: The name Opéra Mort (Dead Opera) brings forth a whole world of symbols and images in itself, like the ruins of an old civilisation. It is devoted to the electronic world of shadows and specters.

This duo with Jo Tanz (who runs the Tanzprocescz label) came to being after the end of the band Reines d’Angleterre we were in with Ghédalia Tazartès. In Opéra Mort we cultivate a bunch of ingredients, insects, slimes, flowers and coffins, a whole vocabulary together and during recordings or concerts our approach is always based on pure improvisation, a deep listening state. It’s like DNA folding and unfolding slowly or microscopic ropes weaving together around a fragment of rusted boat.

You also do a series of short films/sketches. Could you introduce it and talk about the concept?

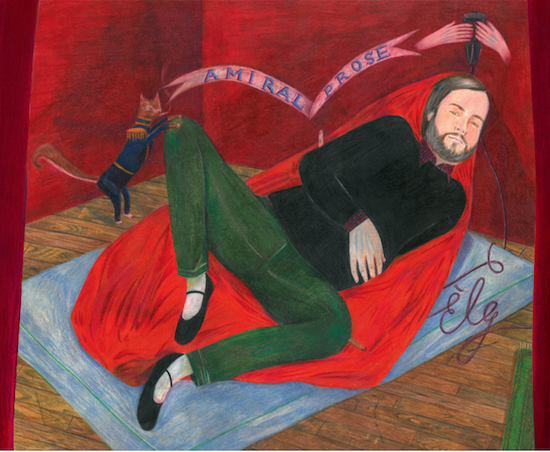

LG: This year I produced a radio drama called Amiral Prose (for LYL radio). It’s a series of 10 minute sketches with guest appearances by some of my favourite artists. It’s a psychedelic juice box that chews up written and improvised comic material with sonic transformations, pieces of real and dream life into a big sticky wad that melts and drips in your ears. And then little people come out of it and light a campfire in your synaptic forest and sing songs about ping pong teachers, arrogant cooks and German teenagers. To me, humour and sound have the same potential for experimentation. In English, a great example of a form that is on the edge of sound poetry and more classical stand-up comedy is Stewart Lee’s bit: "Pear cider that’s made from 100% pears". It is truly hilarious but also very poetic and pushes the limits of temporality and repetition. In the writing and performing that I do with my friend Damien Schultz we bring together the dryness of performance art and French sound poetry into a burlesque circus world and comedy routine. We’ve known each other for twenty years and have always clowned around and improvised but we only started filming and recording a few years ago. Like in ‘Amiral Prose’, the world I develop with Damien tends to distort or mock different aspects of society like hierarchic relationships, ambiguous close friendship or attitudes in the music world or art in general. We try to be as truthful about ourselves as humanly possible.

The music industry has changed a lot with technology (blockchain hailed as the new hype in the music field). Where do you see yourself and your work from the industry point of view and do you think artists still have the role of holding a mirror to the society?

LG: I just read the definition of blockchain on Wikipedia and I still don’t get it. Is it like Doctor Who reinventing PayPal? I see myself as a loner and relatively (because no one’s ever weaned from sodas) free of music industry diktats. I’m not interested in becoming a part of mainstream ephemeral culture. It’s sad but true that too many artists, if that word still has any meaning, lose themselves and the quality of their work suffers when they become famous. It seems like lukewarm becomes the norm. Is it worth trying to figure out why? Anyway, no one (except myself unfortunately) is putting any pressure on me or my work and I would like it to stay that way. I think it’s good to keep the control and follow my own intuitions. Of course, I’m not a naive little white dove, I use promotion and communication when I think it’s necessary otherwise I would not publish anything or play concerts but I don’t want to get wrapped up in a straight marketing strategy because when you start to conform to a societal model or anyone else’s expectations, then you stop questioning and twisting them. And every Korean birthday dog meme is a mirror.

Èlg is part of SHAPE platform for innovative music and audiovisual art, supported by the EU’s Creative Europe programme. He is playing at a Skaņu Mežs event as part of Riga, Latvia’s White Night culture forum, and at UH Fest in Budapest, Hungary, this autumn