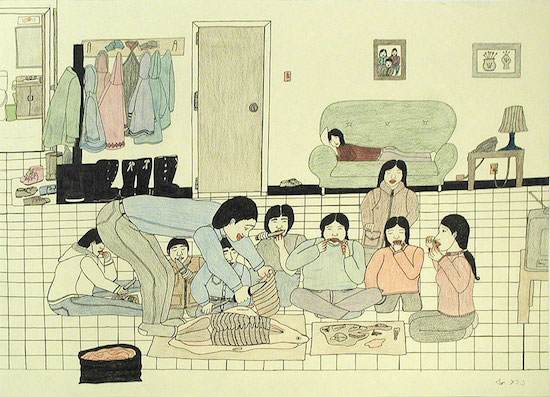

Annie Pootoogook, Eating Seal at Home, 2001, Collection of John and Joyce Price. Image courtesy Feheley Fine Arts

The idea of the far North, the forbiddingly empty wastelands of the ice cap, has long fascinated artists. From the jagged shards of Caspar David Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice (1823-4) through to Darren Almond’s whiteout Arctic Plate series of photographs (2003), there is evidence of urbanites on a deep search for the sublime, for transcendence. This putative escape from the noise of the twenty-first century is something most of us can relate to. But what does the idea of the Arctic mean to the artists who are indigenous to the region? What does the Arctic say to them?

Visit Canada and the likes of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and you will come across examples of Inuit art: carvings made from walrus ivory and the like. Prints feature stylized animals; these are often abstracted, pretty images of bears and birds. The presentation in such museums is careful with much talk of showing ‘culturally sensitive materials that respect the values and spiritual beliefs of the people’. This is as it should be, but it is important to remember that the artists themselves need not reciprocate such respectability. Someone like Annie Pootoogook had a necessary insensitivity to the demands of tourists looking for a facile otherworldliness. Here at Tate Liverpool, as part of the Liverpool Biennial, there is a terrific selection of her prints.

Pootoogook was from Cape Dorset, north of Baffin Bay, on the southern tip of Baffin Island. Here, since 1959, there has been a printmaking studio now known as the Kinngait. The stone-block prints made by the community of artists are rooted in naturalism but Pootoogook (born in 1969) was more interested in the truth of her own life in the here and now. This was a daring move on her part given that she came from a family of more traditional artists – her mother Napachie and her father Eegyvudluk were printmakers and sculptors, her grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona (1904-1983) had renowned graphic skills, and she was the niece of Kananginak Pootoogook (1935-2010), another draughtsman and one of the surprise star attractions at the last Venice Biennale.

Her works were mainly done in coloured pencil and felt-tip pen on paper. There are many interior home scenes. There is an Inuit tradition called ‘sulijuk’ which means ‘it is true’. Pootoogook took this belief seriously and her art shows the truth of her world, warts and all. This is not some mythical happy land of the innocent pre-modern ‘primitive’. This is life after the fall. Her drawings call to mind those images presented to psychiatrists by children who have escaped war zones as with such works as Man Abusing his Partner (2002) which shows exactly that: a man raising what looks like a log above his head approaches a girl dressed in jeans and a pink sweater who shrinks back in horror against a pillow on a bed.

Annie Pootoogook, Composition (Women gathering whale meat), 2003-2004 and Eating Seal at Home, 2003-2004. Installation view at Tate Liverpool, Liverpool Biennial 2018. Photo: Mark McNulty

Annie Pootoogook’s world is a trashed Eden. Boredom is crushing as with Memory of My Life: Breaking Bottles (2001-2) where she is seen outside her house chucking empties against a rock. Entertainment is restricted to nights in front of the TV as with the talk show Dr. Phil (2006) starring dysfunctional families or sticking on a DVD as seen in Composition: Watching Porn on Television (2005) where a couple lie naked in their bedroom staring at the goggle box. Above the set there’s a framed photograph of a couple, parents perhaps, wrapped in furs against the cold. The drawing asks – well, what else is there to do during all those endless freezing winter nights?

There is the occasional tantalizing glimpse of the quotidian realities of Arctic life that grab the city dweller from the south as evidence of a residual exoticism. We see the locals heading for grub we can only imagine tasting such as Eating Seal at Home (2001) where a group sit cross-legged on the floor and chew pink flesh carved by big knives from a splayed corpse. Here they look happy; they take joy in eating. And they look fulfilled too when we see them outside in the snow, wrapped in hoods and padded jackets, hacking more chunks of steak in Whale Composition: Women Gathering Meat (2003-4). Getting stocked up is key to survival as with Family Taking Supplies Home (2006) that sees a mum with a babe in a papoose and dad lugging a crate through the snow. Their footprints are delicate smudges of grey pencil that you can imagine your feet sinking into. More supplies arrive with Bringing Home Food (2003-4) where another seal is brought into the homestead on a wooden pallet.

Annie was well aware of the tradition she was working in and against. Her drawings often reference the drawing hand itself as with her tribute to her grandmother Pitseolak Drawing with Two Girls on Her Bed (2006). Her faux naïf work has a pitch black humour as murky as those Arctic winter nights and some of it is, if you like, a sister to the drolleries of David Shrigley or Norbert Schwontkowski as with Composition: Drawing of My Grandmother’s Glasses (2007) or (35/36) Red Bra (2006).

She exhibited in Toronto and at Documenta 12, won awards, travelled and remembered her journeying as with the brilliantly spiky self-portrait Myself in Scotland (2005-6). Poor Annie. With success she moved ‘outside’, she went south. There is a tragic YouTube clip of her sitting on some stairs outside talking about ‘panning’ in the metro, unsure of how much she makes a day, cash that she spent on cigarettes and booze. Watching her slur that she “prayed every day to restart my life” is painful. She rubs her eyes and explains that she’s “having a hard time with my life lately.” The footage would make a stoic weep. On the 19 September 2016, Annie Pootoogook was found dead in the Rideau River in Ottowa; she was 47. Pootoogook’s truth telling was and is hard for us to bear; she tells us that there are no innocent idylls of man and nature left.

Annie Pootoogook is at the Liverpool Biennial until 28 October