I was explaining to a brunette in black lace why we “would not be doing kissing” – because tonight I was on a date with my man – when our negotiations, at HomoElectric, Salford, were suddenly floodlit. “Boiler Room,” she mouthed at me, taking my hand. The unkissed brunette, my man and I struggled to escape the queer, straight, bi and gender-fluid dancers surging towards the camera lights. Alt-sex clubbers fear, with good reason, that public visibility will pop our private bubble of joy. But then producer Anaïs Bremond and director Stephen Isaac-Wilson asked so sweetly if I wouldn’t mind, for a few minutes… and so I am captured, performing in a gold cut-out bodysuit and pink feathered headdress, in Fleshback, this summer’s short film on the history of queer clubbing in Manchester, on 4:3, the new streaming platform by Boiler Room.

Fleshback mashes archival footage of 90s gay night Flesh at The Hacienda with fat men in Hannibal Lecter masks at today’s raves like Meat Free, Body Horror, and High Hoops. In the back rooms of record stores, sportif lesbian DJs discuss a scene that’s moved on from a post-AIDS, militant queerness, to a straight-friendly, inclusive vibe, anchored in chunky house, sleazy disco and global beats. Isaac-Wilson’s relaxed duologues reflect the camaraderie among Manchester club promoters who play five-a-side football together. Nonetheless, regulars hint at the homophobia of those sexual tourists who fleetingly experiment with queer parties or bodies – their “shame goes inside you”, confesses a trans woman.

Alt-sex clubbing in film has a torturous association with shame. It’s a paradox. On the one hand, Isaac-Wilson’s trans acrobats on meathooks are visual fairy-dust, transforming social documentary into sensory ride. But alt-clubbers – including those of us running away from a film crew – are performing, mainly, to ourselves. Performance artists like Cosey Fanni Tutti, pissing over her audience in a swing (1970s), or Leigh Bowery in the ‘80s, giving birth to his wife Nicola in a torrent of bloody sausages, or Rhyannon Styles, staggering blonde and blood-drenched to the edge of bad taste to INXS’ ‘Suicide Blonde’ (mid-Noughties to date) insist they are unleashing their own urges and exorcising the shame impugned to them. Dressing extrovertly for alt-sex clubbers is mind-cleansing ritual, not ‘fancy dress’. We are pushing ourselves from the inside out, shedding our daily roles to establish safe, non-linear spaces. At HomoElectric and its yonger sister, BabyHomo, we swap life stories, heartbreaks and hugs.

However, fictional films typically harness our display to doom. From Cabaret to this year’s stalker-thriller, also set in Berlin, M/M, nightclubs, in film, are places of identity-confusion and treachery. We can’t tear our eyes from the sparkling ‘transgressors’, the comets who must crash. That’s the story of ‘transgression’. The one redeeming feature of this depressing trajectory is the awareness, from Von Sternberg’s 1930 The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich, onwards, that the straights in the streets and the queers on stage are all performing. Identity politics is a battle of myth and counter-myth, pose versus pose, my life versus yours. That’s why Voguing emerged from the black, queer ballrooms of 1960s Harlem to rage in 80s New York and was championed by Madonna, when the US government refused AIDS medication for a ‘gay disease’.

Intelligent films have presented the downfall of queers in films as a reflection of the downfall of society. In Cabaret (1972), Liza Minnelli’s Sally Bowles, a sluttish showgirl in 1930s Weimar Berlin, sings of the comeuppance of escorts dying from “pills and booze.” Her punters, conversely, sing of beauty and Nature and, by the end of the film, have donned Nazi uniform. It’s pose versus pose and Sally must lose. When Sally and her boyfriend (Michael York) both sleep with a wealthy baron, they forfeit their love and abort their baby. The arc of the queer fable is tragic. As an interviewee in another of this summer’s films on clubbing, Studio 54, says, “nothing this fabulous could last.”

Studio 54, a feature-length documentary on the iconic club created by Ian Shragar and the late Steve Rubell in a Vaudeville theatre, sumptuously reconstructs the making of a fable. Director Matt Tyrnauer, a correspondent for Vanity Fair is a schmoozer extraordinaire of the entertainment industry, who recently directed the story of alt-sex Hollywood procurer Scotty Bowers in Scotty and The Secret History of Hollywood. Deploying the queer arc of doom, Tyrnauer dishes up a glossy flicker of bare-breasted maenads, transvestites and black groovers. It’s addictive eye-candy; but we know things won’t end well.

Tyrnhauer displays, to the dollar, the cost of Studio 54’s theatrical design and courting of celebrity. Presided over by regulars Liza Minnelli, Warhol, Bianca Jagger and Liz Taylor, it was fabulous. Fabulousness, being a heightened reality, is the home of monsters and alternative sexuality. If some queers find this reductive (Rubell himself was quietly gay), they surely can’t begrudge the unifying force of the fable? As Robert DuPont, one half of Warhol’s blonde ‘DuPont Twins’, recalls of 54, “you could see gay men kissing without any judgment.” In archival footage, a 19 year old Michael Jackson slinks shyly into the office of the late Rubell and coos at the “genuine” sincerity of this master faker. Jackson’s pimply apple cheeks shine as he happily describes the club exploiting his fabulousness as a place one goes, “when you want to escape. When you dance here, it’s just free… you’re free.” In that paradox typical of clubland, “freedom” is created by communal performance. The club was a haven for black and white and gay lovers at a time when mixed-race couples and trans people were brutally attacked in the street. Tyrnauer, well-versed in the cultural wars of counter-myth, presents a perky Chanel 11 News report on Studio 54: “the disco dancer becomes the performer”. We know mainstream society won’t tolerate such sublimation; this club must die.

In an otherwise matter-of-fact documentary, Tyraneur’s use of Rubell’s hallucinogenic home movies, in Studio 54, are oddly moving. Every graceful, giddy limb pulses with the after-image of transgressors punished in the collective imagination of film and literature. Rubell, who died at 45 of AIDS-related illness, understood the carnivalesque power of characters like Disco Sally, an aging accountant by day and glitterpuss by night. His is the party of our dreams. Trans dancers wreathe constellations of opalescent balloons through the crowd, while beautiful young theatre workers who rigged the hurricane that blew at 1.30 every night, vanish, under the onslaught of AIDS. IIt doesn’t take Shragar, smacking his steely lips in a mafioso performance expertly coaxed by Tyrnauer, to announce Studio 54’s destruction. Disco Sally signified it was coming. Rubell and Shragar’s well-documented imprisonment for tax fraud, over-stretched by Trynauer, is prefigured by the portraits of sexual grotesques in film.

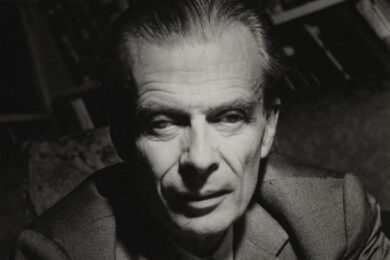

Encountering alternative sexuality, the screen becomes a fun-house of mirrors. Minnelli’s Sally Bowles is a red-lit, loveable clown: bug-eyes and childish lips, gutsy contralto, déclassé proportions. Dietrich, in The Blue Angel, is a sick clown. Her cheekbones are unhealthily slanted; her voice too manly; those sky-high eyebrows tilting the strings of ‘Falling In Love Again’ warn us she’s a jilt. Similarly, Jon Voight’s blonde lug of a farmboy, in Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), is a curiosity to the Warholesque circle of New York fashionistas who briefly gild the ill-fated hustling of two oddballs (Voight and Dustin Hoffman). Voight is a swollen-limbed abscess, Hoffman a rat-faced dwarf. These counter-caricatures cannot fight the status quo. They must lose.

Modern directors fall into this traditional narrative trap. Sean Baker’s warm and whizzy Tangerine (2015), disrupts the underworld spectacle of trans hookers and performance artists by soaking them in sunlight and filming them, close-up and personal, on an IPhone. It’s a beautiful trick but it’s the same old trick, nonetheless. Meanwhile, Drew Lint’s 2018 blue-washed psycho-thriller M/M, set in the Berlin techno scene, expresses homosexuality as a murderous longing for a missing self; the ultimate identity theft.

Set in a Nottingham high-rise of pot plants and IKEA duvets, Weekend (2010) is the post-clubbing, come-up movie, heralding the arrival of optimistic romantic Andrew Haigh. His HBO series set in San Francisco, Looking, comes closest to the sexual explorations of alternative clubland today: its trustful minglings of straight/queer, monogamous/polyamorous, gorgeously fat, brash and reserved. “Be Ugly”, the motto of HomoElectric, is celebrated in wrinkly, outsize sex by Haigh’s Bay rollers. Unfortunately, Haigh’s penchant for fairy-tale monogamy, in his dud film of Looking, kills off his fascinating creation with an ending lifted from straight culture: a circle of married-off pals in a café; forever F.R.I.E.N.D.S.

Thus, whenever a film crew arrives at an alt-sex party, we worry the mainstream – merchant bankers, drunks in Ben Sherman shirts, marital happy-ever-afters – may follow. Torture Garden, in Brixton, died for me, personally, when a team from Goldman Sachs held their Christmas party at our BDSM playground.

I returned to the HomoElectric crowd, at its sold-out younger sister, Baby Homo, recently. Down the old alley, beneath the lighthouse of Strangeways Prison, undressy punters haunted the ropes, hoping to be admitted to Salford’s White Hotel. I scanned the sweats, anxiously, for a painted Minelli beauty spot, a Vaselined curl, a tell-tale grin that meant we’d survived the exposure of Fleshback. Then I saw Brett, in his sequined fireman’s helmet, a gift from Manchester’s queer ex-mayor. I hugged out the heartbreak of Ron, a handsome handywoman, intoxicated by the goodwill of her first ever Baby Homo. I talked art in a kissing circle with Nicholas, a 6ft 4 blonde Viking who loves 70s dresses – and I knew our ravers’ paradise was safe, for now.

Fleshback, directed by Stephen Isaac-Wilson, is available on streaming services from this summer