I’ve tried quite hard not to develop a technical language for what I do. I find a lot of the practical discourse around writing quite alienating. Fiction for me is a way of exploring the limits of my understanding. Too much certainty starts to feel like constraint.

Music, then, is how I conceptualise what I hope to achieve through my writing without pinning it down so concretely that it becomes moribund.

Sometimes, as with the Herndon piece I’ve picked below, the music speaks to the themes and aesthetic of the novel I’m working on. Other times, as with a lot of the jazz I was listening to when I began the book, it informs my own practice – a creative method or a feeling I want to access while I’m working.

David S. Ware Quartet – Aquarian Sound (Live)

Perfidious Albion was written in the shadow following the publication of my debut, Idiopathy. Suddenly, a practice that had always felt wholly mine was both public and strangely professionalised. How, I wondered, could I retain or regain the sense of looseness, almost naivety, I’d enjoyed when writing was simply something I did for myself, alone, unseen? To feel exciting, writing for me has to have a sense of risk, a feeling that it could conceivably go wrong – precisely the feeling that can be suffocated by a surfeit of forethought. Publication, though, and the impression of an imagined audience, can tighten you up, encourage a retrenchment into your creative comfort zone.

My solution, initially, was to work in as improvisatory a way as possible. Because I knew the novel would be about the changes in collective and individual senses of identity brought about by the internet, I decided to deliberately disregard the usual writerly advice to disconnect, and allow my online experience to inform my writing as much as possible – to try to respond and adapt, fluidly, not only to what was happening, but to how my consumption of what was happening informed my daily emotional experience.

In an effort to sustain this, I spent a great deal of time listening to free jazz. This piece in particular is one I returned to repeatedly because of the way it marries abrasive free improvisation with a tight narrative structure. It builds beautifully – opening with just William Parker’s five note bass figure, then Shipp’s broad, resonant piano chords with the percussion underneath. Susie Ibarra is one of those drummers who reminds you that so much of the kit is tuned. Her drumming is almost melodic – you find yourself trying to hum it afterwards. Finally, Ware comes in with that really throaty, pungent tone he has, at first just stating the theme, and then slowly starting to cut loose. The way he builds from those careful, deliberate opening notes into the outer limits of his technique and sound-world is so compelling. It’s easy to think of free improvisation as just undisciplined noise, but Ware’s restraint as he heads deeper into his repertoire of overblowing, circular breathing and screeching is what gives the piece its dynamic range and sense of tension and release. You never feel with Ware, as with some improvisors, that he’s just cycling through a grab-bag of tricks. Everything he does is at the service of the piece, and yet, equally, you feel he can go anywhere. It’s the perfect balance of freedom and control.

Suzanne Ciani – Buchla Concerts

Analogue synthesis seemed to ease the potential tension between the organic possibility of jazz that had informed my sensibility, and the chilly, digital sonic landscapes I felt would probably inform the book’s aesthetic. The distinctly West Coast acid-head philosophy behind the Buchla was a particular appeal. This wasn’t a machine that was meant to realistically synthesise existing sounds, it was a gateway into sounds that had never been heard or created before. These performances by Ciani feel like manifestos of sonic possibility in that sense. She’s performing in the mid seventies, so the loft jazz scene would have been an influence, along with what was happening in minimalism, but it’s like she’s finding a way to bring pattern and exploration together. She finds these wild tones in the Buchla – mechanical bleeps and screeches that I suppose are the technological equivalent to someone like David Ware’s overblowing – but there’s also all these lovely, glistening, arpeggiated sequences. To me it’s just the sound of total possibility. There are nods to the jazz and classical tradition in there, but Ciani is using them to map a technological future that at the time was just barely emerging.

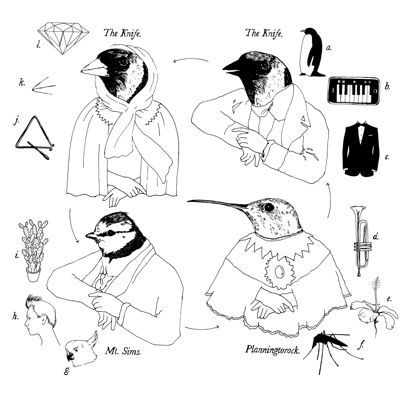

Holly Herndon – Chorus

Perfidious Albion has its conceptual roots in the idea of the digital dualism fallacy – the way we kid ourselves that our online and offline lives are separate, or that the ‘digital’ world somehow doesn’t enmesh with and inform the analogue one. I was interested in the places where these false distinctions break down. We might tell ourselves that our ‘real’ life is the one we conduct offline, but our online world is increasingly the setting and repository for some of our most profound emotional experiences.

Holly Herndon’s work as a composer and a thinker is one of the best explorations of this I know. Around the time she was promoting her Platform album, she talked about how the laptop was the most expressive instrument she could use because it contained so much of her life – Skype chats, documents, journal entries, found sounds, etc. I think this is such a compelling idea – have we ever had an instrument before which doubles as the composer’s archive and means of communication?

What I really admire about Herndon is that, while her music has this very complex theoretical underpinning, it never stops being exciting on a purely musical and rhythmic level. This was something I was always wrestling with when I was writing Albion – how to make sure a novel inspired by quite abstract concepts doesn’t just become a collection of ideas? How to make it still feel like a novel?

Herndon’s Chorus points the way in that sense. All her preoccupations are present in the arrangement: human vocals are manipulated almost to the point of digital abstraction; synthesised noise both underpins and sometimes obscures her singing; there are flutters of quasi-baroque choral singing. Everything is chopped into this state of glitching, staccato bewilderment. Suddenly, though, and very beautifully, it all just coalesces: the beat seems to shape itself out of nowhere, and it becomes this unexpectedly propulsive dance track. It’s so beautifully done, and in its construction as much as its thematic preoccupations, Herndon seems to be picking at another false binary: ‘entertainment’ vs ‘experimental’ or ‘conceptual’ art. Why can’t something be both?

Visionist – I’m Fine

Once I was at the editing stage I felt I was no longer, emotionally and intellectually, in the right place for jazz. It wasn’t about endless invention any more, it was about polish. I wanted the book to have this sheen to it – this sense of a slightly impenetrable, glassy surface that speaks to a sense of both modernity and distance. It was a tricky time because I was trying to shape something that had been begun with the intention of being very loose and free into something tightly patterned and, in places, almost airless, which I hoped would convey some of the emotional texture of our present social and political moment.

This particular kind of ‘weightless’ Grime was everywhere while I was working. It’s like Grime stripped down and abstracted – pushed into this minimal, drained state. I felt it had the exact quality I was looking for. Also, I’m just a complete sucker for chopped-up vocal samples – the more abstracted and pitch-shifted the better. It really fascinates me how they take on this completely new feeling of beauty through processing. They no longer resemble anything approaching what we would think of as a natural singing voice – they’re completely inorganic – but at the same time they’re so haunting and evocative. Visionist’s pair of I’m Fine EPs use this technique brilliantly to evoke a distinctly of-the-moment sadness. We’re very quick, I think, especially when thinking about literature, to associate the stripped-down, the untreated, the direct, with a certain kind of emotional authenticity. Music like this reminds us that sometimes the heavily-processed, the stylised, the unnatural, is just as gorgeous, and is sometimes a better reflection of the world we live in.

Joni Mitchell – Hejira

Prior to working on the novel, I’d read Vivian Gornick’s fabulous work of criticism, The End of the Novel of Love. Consequently, I was determined that what slight redemption might be offered to the characters in the book would not come in the form of a romantic relationship. Indeed, I was interested to see if I could liberate a character from even the very idea of romantic love, from the sense of it as one of many suffocating structures amidst which we’re expected to shape a life and identity.

Hejira is one of those songs where you somehow feel you’ve been listening to it longer than your current lifetime. It seems to speak to more than one geological era – it’s that mythic and profound. It’s also one of very few songs to so perfectly convey the complicated feelings of a break up when the break up in question is both painful and necessary. It’s neither self-pitying nor celebratory, neither Unbreak My Heart nor I Will Survive. It doesn’t plead, but nor does it quite revel. A lot of its evocativeness comes from its voicing. Mitchell, for far too long denied the guitar-hero status she’s due, tended to invent her own tunings, and so a lot of the song’s emotional undecidability lies in its harmonic ambiguity. In refusing to predictably resolve in a musical sense, it rejects easy resolution in a narrative and emotional sense.

Then, of course, there are the lyrics, which walk this extraordinary tightrope between dry-eyed realism (‘I’m so glad to be on my own’; ‘I know, no-one’s going to show me everything’) and an almost transcendental wisdom (‘We’re only particles of change’; ‘We all come and go unknown’). What I find so affecting about the song is that it recounts a simultaneous return to oneself and to the world. The narrator is ‘returning to myself/these things that you and I suppressed,’ but she also sees ‘something of myself in everyone/Just at this moment of the world’. It is, as the title suggests, a journey, but Mitchell, always able to hold her inner cynic and romantic in happy balance with each other, is too smart to give us easy escapism. She knows that life’s journeys tend towards the cyclical, that things can’t be learned just once, they have to be re-learned repeatedly. That’s why she knows she’ll go through all the same shit all over again. Novels struggle with this idea — we expect a degree of change or development in the characters we have spent time with. Songs are better placed to capture that moment when a person is poised: incompletely changed, and only partially free.

PJ Harvey – England

‘England, you leave a taste. A bitter one.’

Self-explanatory this, really. Let England Shake is my favourite PJ Harvey album, and this is its standout moment – impassioned, embittered, loving and loathing. Like Mitchell, Harvey is so good at finding a way for the sonics to redouble the work of the lyrics. There’s this really forthright, slightly pastoral melody, and then underneath it the choppy undertow of that haunting Kurdish folk song sample. You know the elements of Englishness she’s holding in tension with each other here – the same elements we’re all now holding in tension every day in this occasionally beautiful but profoundly corrupt and morally distorted country. I completed the first draft of Perfidious Albion in 2016. I’d begun it as a kind of near-future satire, but by the time I finished it it honestly felt as if England had decayed around me. It felt like our collective nadir, but in retrospect it wasn’t even close.

Kanye West – Ultralight Beam

Obviously, it’s a complicated time to be a Kanye fan, but I’m just going to be upfront and say that sonically, if not culturally and politically, he’s a genius. Of all of his albums, Pablo is the one that’s most important to me emotionally because of when and how it was released. I was approaching exhaustion point with the book. It had grown into this enormous, almost unmanageable thing. I was trying to do what you always have to do with a baggy first draft if you’re not, as I’m not, someone who writes according to a plan: take this raw version of what you were trying to express and shape it into something someone else could conceivably relate to, without at the same time stripping it of its energy, its idiosyncrasy, and whatever essence you want to hold over from your original conception of the project.

Just as I was engaged in this most difficult part of the process, Kanye released Pablo, and then, after releasing it, he edited it while everyone watched. I’m not saying that my editing a novel is in any way shape or form a comparable experience to Kanye finishing an album, but the simple fact of seeing the process as it took place, and being reminded of the power of small changes and adjustments, was hugely motivating and inspiring, and it made me feel connected to a musical artist I admired in an entirely new way.

Beyond the originality of its release strategy, I was also struck by the beauty of the album’s opening, Ultralight Beam. For me, it’s Kanye at his most visionary – The-Dream’s always-gorgeous voice floating over that reversed synth tone, the choir, Kanye’s trademark autotune, and then those surprisingly fat drums underneath, staving off a certain kind of sonic sentimentality.

The moment that always stays with me, though, is right at the end. As I was writing Albion I kept returning to this idea of transcending the digital/analogue divide, revealing its true porousness, and what that might look and feel like in the context of our daily lives. At the end of Ultralight Beam, which is essentially an afrofuturist gospel song complete with benedictions and the casting out of evil, the choir build to a speaker-shaking, spine-tingling crescendo, only to distort, jarringly, into clipping. The first few times I listened to it I was confused. I even played the track through different headphones to check. A bit of googling revealed I wasn’t alone – others had noticed it too, and were baffled.

What fascinates and frustrates me about the discussion surrounding Kanye and his music is that it’s all too often assumed he does things by accident, or that he’s too chaotic to pursue a coherent creative vision. The clipping on Ultralight Beam was just another example of this. People said he hadn’t even bothered to master the album properly, that it was evidence of Kanye’s slapdash, careening approach. In my view, though, it’s perfect. Clipping is the digital equivalent of old-fashioned distortion – it’s what happens when the signal is pushed too far into the red. If you were to look at a visual rendering of the waveform, there would be no emptiness at its edges, it would both fill and exceed the space available for it. Kanye’s use of clipping right at the pinnacle of the gospel choir’s intensity is, I think, his attempt to capture a moment of total transcendence. The choir literally cannot be contained – they have punched right through the digital wall and ascended into whatever lies beyond. Kanye knows that liberation, while beautiful, is often messy and imperfect, and leaves in its wake unwanted, sometimes ugly artefacts. It was something I’d tried so hard to visualise for myself, to find words for, and Kanye, genius that he is, rendered it in half a second of glitching sonics.

Perfidious Albion, by Sam Byers, is published by Faber on 2 August