”L’art du cinema consiste à faire faire de jolies choses à de jolies femmes” – the art of cinema consists in having pretty women do pretty things. This quote, from Francois Truffaut, was how I chose to open my lecture – the last of four taught on the directors of the French New Wave at the Department of Continuing Education at Oxford University last autumn – on Agnès Varda. I had decided to save Varda for last, and Truffaut’s quote, frequently remembered in the wealth of critical writing on the French New Wave, seemed to me a good entrée en matière to discussing the postfeminist narrative of Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962).

So far into the course, I had approached the movement according to its standard historical – and therefore predominantly male – perspective, placing the films of Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Alain Resnais within their cultural context in postwar France, stressing the way in which the young, anti-orthodox filmmakers simultaneously called for a reassessment of cinema as art and for a relaxing of the rules of filmmaking. By the end of the day, I had yet to discuss the New Wave’s inclusion of women and its representations of gender relations, which jarred with the movement’s professed radical attitudes towards both film and the changing landscape of France’s society and culture. My lecture on Varda deliberately approached her work through the perspective of her uniquely playful, even generous redressing of the codes of female representation within the movement and in French cinema in the broader sense.

My students were all die-hard francophiles but none of them came from a film studies background. They were mature students, and a majority of them were women. Truffaut’s quote — which I dropped without preamble — elicited a general sneer in the class: my students knew, from the title of my lecture, that I was about to discuss the place of feminism within the historical moment of the New Wave, and the quote alone adequately summed up the viewpoint of the male film director (by no means Truffaut alone in the New Wave movement) who, equating his art with having women please him visually, is distracted from the possibility of engaging with a woman’s imagination. For a woman to do ‘pretty things’ here means of course for her to do them on camera, not by means of a camera, or surrounding the process of filmmaking.

The notion of ‘pretty’ is itself confined to traditional standards of male visual pleasure which Truffaut would not call into question. When the Cahiers du Cinéma released a special issue on the “Nouvelle Vague,” co-edited by Truffaut, in December 1962, only three women figured in the list of young directors associated with the movement: Paula Deslol (La Derive), Francine Premysler (La Memoire Courte) and Varda, whose debut feature La Pointe Courte — now deemed to be a forerunner of the New Wave — had anticipated some of the stylistic innovations of the movement, many of which would be credited to Truffaut’s 400 Blows a few years later.

On the cover of the issue, meanwhile, were two young brunettes in black and white swimwear, standing atop the roof of a ship’s cabin, holding the mast with one hand and raising the other fist to the sky, presenting a confident picture of youth itself, as unquestioning as their smile to the camera. If the youth that Truffaut and his companions had to offer the movement was in their ingenious questioning of film conventions, the female body, meanwhile, was innocently contained within its traditional aesthetic role.

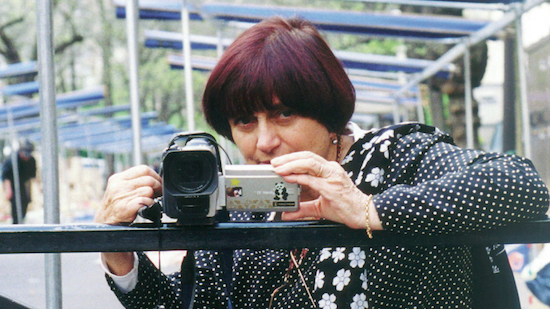

Critics were slow to acknowledge that, had the magazine listed the names of actors, producers, cinematographers, camera operators, costume and set designers involved in the films of the New Wave, the list would arguably have included quite a few more female participants in what was already hailed as French cinema’s aesthetic revolution. Varda, whose lifelong career is currently the object of a two-month BFI retrospective, was always vocal about recognising the work of cinema technicians, regardless of gender, which the anti-democratic auteur theory outlined by André Bazin and the Cahiers critics was always bound to undermine. She was one of the 82 women who demonstrated against the lack of female presence in the film industry at Cannes this year, and for her this also means there should be more female technicians. She herself came to filmmaking via photography, starting her professional career taking portraits of stage actors at the Festival d’Avignon, France’s most prestigious theatre event.

Bearing in mind her collaborations with Alain Resnais and Chris Marker from the mid-1950s, film historians tend to identify Varda as belonging to the Rive Gauche gang, often presented as a lesser-known sub-clan of the New Wave family, a group which was not directly involved in the editorial activities of the Cahiers du Cinéma and who distinguished themselves from the Cahiers group in that they were primarily guided by the practice, rather than by the theory, of cinema. Varda, for example, was not a self-proclaimed “cinephile” in the way Truffaut and Godard, the established film critics, were. She did not attend the “cine-clubs,” whose debates they largely dominated.

Consciously or unconsciously aligned with the immediacy of the cinéma verité movement in documentary filmmaking, Varda’s early work deployed a radical curiosity and a closeness to the men and women who composed the changing society of post-colonial France. In Cléo de 5 à 7, the plot is driven by the female protagonist’s impulsive movement through Paris and the chance encounters that result from her journey. Critics have commented on the way, in Cléo, the background cast shares centre stage with the title heroine. A female taxi driver delivers an anecdote about what it’s like driving a taxi as a woman in present-day Paris and thus contributes to the story by interrupting the flow of Cléo’s self-focused thinking. In the background, a real-time news report on the radio speaks of war in Algeria, information which the characters can take or leave, but with which they must coexist, whether they like it or not. Even in those of Varda’s films which are fictions, far removed from the personal-documentary form she would experiment with later on, attention to people is political, yet it is rarely an occasion to theorise about politics. In that sense, her cinema is radically contrasted to that of Jean-Luc Godard, which exists in the realm of ideas, both formal and political.

As I discussed in class, the slightly formulaic distinction between two groups does not mean that Varda had no affinity with the members of the so-called Cahiers gang. She was a close friend of Godard’s from the beginning of her filmmaking career. In the early 1960s, shortly after Jean Rouch’s Chronique d’un été was released, Varda had Godard and his then partner Anna Karina play in a short film of her making, Les Fiancés du Pont MacDonald ou (Méfiez-vous des lunettes noires). The two-minute short, a pastiche of silent comedy, was designed to play as an interlude in the second half of Cléo: a film within the film to relieve some of the tension of Cléo’s narrative of existential unrest as she waits for the results of her cancer tests. The film was also an excuse, in Varda’s own words, to get Godard to remove the shades he customarily wore, and to reveal his eyes to the camera in the process. The fact that they were friends helped, as she recalls, that he agreed to shoot this script about sunglasses where he has to take them off, allowing the camera to capture the large eyes which reminded Varda of Buster Keaton. Reminiscing about the shoot decades later, Varda makes no secret that revealing the beauty of Godard’s eyes was part of the point all along.

In the short, a pair of lovers part on the MacDonald bridge on the Canal de l’Ourcq in the 19th arrondissement of Paris. Because of the sunshades he is wearing, the male protagonist (played by Godard) thinks he witnesses his lover (Karina) fall on her way down to the banks of the river to meet a premature death. Shedding tears over her tragic passing, he finally removes his sunglasses, revealing an expression not unlike Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s in The Passion of Joan of Arc to the camera’s close focus: consumed with emotion, unguarded, vulnerable. Through the naked eye, meanwhile, the same character soon starts seeing life in a positive light again, realising that his darling is in fact still alive. Before they seal their reunion with a kiss at the top of the bridge, Godard’s character throws his shades into the canal exclaiming “Maudites lunettes!” as the piano playback fades out.

While Karina’s burlesque act casts her as a doll-like character — a nod perhaps to Godard’s two-dimensional representations of desirable women, consistent throughout his early career — the film also asks Godard to bare the mask of authorship to reveal a languorous, some would say feminine expression to Varda’s camera, unveiling some of the vulnerability at the site of the auteur’s gaze. Cléo, which remains one of Varda’s best-loved films in and outside of France, addresses the question of female identity through and beyond the relentless pressures of the male gaze, a question which her New Wave peers did not engage with in a politically-conscious way – as Truffaut’s quote alone amply suggests. In this cheeky interlude to Cléo’s tale of self-discovery, Varda makes room for the female gaze, or at the very least for a form of visual pleasure which is distinctly female. It is Cléo and her friend Dorothée who view the film together from the tiny window of a projection room, a moment of complicity between the two women who both make a living from being looked at, one as a pop music icon, the other as a sculptor’s model.

Varda’s latest film, Visages, Villages (2017), which is to be released in UK theatres in September, documents a failed reunion between Varda and Godard at his house in Switzerland, whereby, after having arranged to meet there, she finds his door closed and a cryptic message scribbled on the window pane. The scene is presented as the anticlimax of a collaborative documentary in which Varda and 33-year-old French muralist JR go on a road trip across France to meet, film and photograph the country’s village-residents, many of whom respond with generosity in letting the pair capture their image. Significantly, Varda spends the entire film asking JR to remove his shades and hat, the costume of his own artistic persona, but it’s not so easy. JR refuses, Varda becomes upset. “I like to see faces,” she says.

On the train to see Godard at the end of the film, Varda plays Les Fiancés du Pont MacDonald for JR on a tablet. Filming Godard in this playfully objectifying way was no doubt daring, perhaps even radical – I don’t think it has been attempted by a filmmaker since.

Since the 1960s, the cult of Godard’s image has only grown alongside critical obsession with his film style: in Michel Hanazavicicus’ biopic Le Redoutable, the relish in representing Godard the man, with his childish self-importance, obtuse political obsessions, and often comical mannerisms, is indistinguishable from the pastiche of his filmmaking style, the primary colours, the jump cuts, the anti-narrative of an existential voice over. It is in this that Varda’s surrendering of Godard’s image, having crept up again in her late work, a creative experiment turned into a leitmotif, is worthy of attention. In chasing Godard’s elusive image, Varda’s short alters it by a small measure, which is more than Hanazavicicus’ disguised hagiography could ever have done in the way of irreverence.

Part of the enduring appeal of the French New Wave as an aesthetic movement is in the collective friendship and collaborations of these emerging directors who started off with no means or credibility and began by taking filmmaking from the studio to the streets. I can imagine nothing less than friendship in Godard lending himself to the reversal of gendered roles, in letting another viewpoint determine both the gaze and its image of desire, while shooting Varda’s short. Hiding from Varda’s camera at the end of the documentary, Godard has relinquished the former playfulness of their relationship, and from the perspective of the viewer also, it is disappointing. Varda, marginalised from the canon since her husband Jacques Demy’s death in the early 1990s, and only recently rediscovered as auteur figure, seems symbolically scorned again by the male canon at the site of Godard’s closed door.

None of my students had had a chance to see the new Varda last year at the time of the course – it is only to be released in the UK later this year – but after having just watched Cléo for the first time, one of them raised a hand to ask for permission to argue that it was a hard situation for men to be in to have to understand the female perspective, when women themselves did not understand the first thing about who they were or what they wanted – a fact he claimed to be acknowledged by psychologists worldwide. Before I could begin to form an answer to his statement, another student called him out on being a misogynist, an insult which he shrugged off as one inevitable consequence to having spoken his mind. As the students left the classroom, a couple of them told me: “Please don’t pay attention, he’s like this in every class, it doesn’t matter what the subject is.” I took this to mean that the student was always ‘provocative’, but I could not let this undermine the gendered nature of the very strong discomfort he had expressed. It confirmed something which I’d already sensed in other contexts besides teaching, that when you ask someone, quite simply, to consider that their point of view is not universal, it will often feel to them like a great injustice. Senseless provocation can certainly be one way for this sense of injustice to speak through, and part of me feels that it is better for this to be heard than to be ignored.

Since the release of Faces, Places, many Q&As have focused on Godard’s haunting absence in the film. JR has suggested that it may have been Varda’s question, to Godard’s assistant, while making arrangements for the meeting to take place – “does he still have his dark glasses” – that made him recoil and change his mind about meeting up altogether. “My theory is that he wanted to write the film,” JR concludes at the Lincoln Center Film Festival last year. Incidentally, seeing a tearful Varda on camera — because a long-time friend has failed to come to the rendez-vous, because the message he left behind were the same words he wrote to her when Demy died — reminds me, by an effect of delayed inversion, of the fake tears pouring out from behind Godard’s shades. It’s like a conclusive afterthought to a once hopeful take on the possibility of sharing the filmmaker’s creative agency, within and across gender relations as they exist and as they could be.

Agnès Varda: Vision of an Artist is at the BFI Southbank throughout July