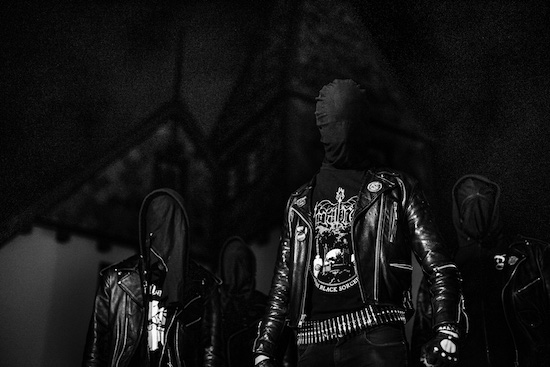

On a street pockmarked by snow and ice, a group of men stride towards the camera, their heads scratched from the film as if dissolving into bursts of electrical crackle. From a single hooded cloak stretch six arms gesturing quizzically, theatrically, protectively. Five figures proffer animal skulls inscribed with occult symbols. Welcome to the dark world of Icelandic black metal, as captured by the lens of photographer Verði ljós.

For three years ljós has been documenting the black metal scene of his native country. And when he’s not taking pictures, he’s making the music himself. Since 2006, ljós (whose real name is Hafsteinn Viðar Ársælsson) has been fashioning an “apocalyptic, cyclical strain of dissonant aggression” (tQ) under the name Wormlust. But his new book, Svartmálmur, out now on Ditto Press, proves him to be as fine an artist when crafting with light on paper, as he is recording sounds on tape.

The Quietus caught up with Verði ljós to talk about the book and the Icelandic black metal scene at large. And he very kindly curated an exclusive playlist of some of the finest noise Reykjavik has to offer.

What was your first entree into the Icelandic black metal scene?

In my teens I gravitated towards hanging out with kids that had ventured deep into that world. They had their own band which fascinated me and so rather than be stuck as the hypothetical roadie I decided to learn an instrument. Not that they were virtuosos by any stretch of the imagination. We were basically only listening to the black metal than came out of Norway at the time. It wasn´t until a year or two later that things like the French scene in the 90s started to trickle in. I don´t know if you could call that a scene at the time since there were at most three bands active at the same time and things were more insular between each group. However, the band my friends had, Myrk, which I ended up joining, became kind of influential to what later became the start of the movement we have now – maybe not so much musically, more introducing the next generation to this style of music. Keeping the flame alive in dark years.

What were the circumstances that led you to start this series of Icelandic black metal artists?

It started with me happening upon a book by chance at a library. It was a photo book about the Icelandic psychedelic scene in the 60s. It had all these vivid shots of groups I knew growing up but had never seen. It resonated with me for some reason and it got me thinking about the fact that there wasn’t anybody documenting my own scene. I decided then and there to do the task. I think it’s because I didn’t want to have a scene come and die with not much to show for itself, visually at least. The music itself will probably outlast us, but future generations that I hope will carry on where we leave off should now have an understanding and be influenced about what we were about.

How did you decide which artists to include and which not?

Well, there is an unspoken line drawn by the bands themselves, most of the circle rehearses in the same place and the bands share members with each other. Before recently the overall scene could be broken into two camps – the Misþyrming side and the Svartidauði side – and then you would trace the acts eminating from that outwards. But since the Roadburn Festival commissioned a piece from members from each camp it’s all intermingled, in terms of artistic output. It´s kind of difficult to explain why a band fits in the scene. It’s not really just aesthetics and approach to music – there is a social factor thats hard to quantify.

Over how long a period of time were these photographs taken?

I started photographing for this project on 21 December 2014, so over three years. I remember the date because it began with me doing live shots and backstage photos of the annual And-kristni festival here in Iceland. I decided to use film for the project at that stage, but since I was learning as I went along, the photos from that night ended up being unusable due to my lack of skill. At the start I had the same visual goals but not much know-how. It’s like trying to reach out for a light switch in the dark. The project itself kept challenging me to improve as an artist.

Your style of photography in this book is often very expressionistic – these certainly aren’t just simple portraits! – what were you trying to say or to capture or to express here?

With the portraits I am trying to convey the internal world that the artists construct within themselves while making the music. My own experience being photographed probably led me there. The frustration that goes with being photographed by someone that doesn´t live in that world. The landscapes in the book are then in a way more like mirrors to the portraits and I also try to reflect what the bands’ aesthetics are, rather than impose my own upon them. Overall, I guess you could say that I am trying to visually convey where their music takes you. It’s a kind of silent album experience.

What do you think makes the black metal scene in Iceland unique in comparison to black metal in other countries?

How it’s almost like one big band in way, aesthetically, and how the members are spread out. Paradoxically each band influences each other but they don´t really sound like the rest even though they share people. Each band is their own school of sound – possibly similar to the big bands of the early norwegian scene. It grew like a desert flower in the cultural music wasteland of Iceland and managed to become influential on the world stage. We are cut off from real cities and the kind of cultural outlets I can only imagine, so that is a big factor. If you drive the main road for a couple of days straight you will end up where you left off. Getting off this rock is a big impetus.

How have you seen this scene change and evolve over the period of your involvement?

I have seen the death of one scene and the birth of another. From three active bands on the island and mailing out demos, getting no replies, to playing to 3,000 people at Roadburn. How things have slowly shifted is very surreal to me. I think the biggest change was, with time, the music started to get actually really good. The first scene I was involved in didn’t really put much that effort into the music. Now you got albums like Flesh Cathedral by Svartidauði, created and laboured over for years. Masterpieces.

The change in attitude and work ethic was probably the most important change, getting things done yourself and releasing music that a lot of effort has been put behind. The number of people is probably only twice as much as it is was back in 2002 but the amount of work that is being put out is a lot more.

How did this book itself come about? What made you think this would work as a book?

Well, the actual object came to be when I reached out to Ditto, who are publishing it. I went to Paris, to a book expo, with the intent to get the project published and their books told me we had very similar approaches. Books like God Listens to Slayer by Sanna Charles, as well as Sha•man by Sanna Charles and Mark Wagner were things I immediately resonated with.

I knew it would work as a book because it’s an insular world that most people don’t get a look into. I myself am fascinated by looking into hidden things and honestly assumed that everybody else would be too.

There is also that aesthetic link that the bands share. It wraps the scene up real nicely by itself.

It might also be because I come from the music side, primarily, where we are obsessed with physical formats. The goal always being to work towards presenting a tangible and definitive object. So, in putting on the photographer’s role, my mind must have gravitated towards that medium’s equivalent of the LP.

Svartidauði – ‘Flesh Cathedral’

The alpha, so to speak. They ushered in the current wave of Icelandic black metal. Their album is a masterpiece, truly. I’ve been fortunate enough to see the band evolve as a live act, but they were pretty strong right out of the gate with their demo in 2006. First band to bring a sense of ritual and esoteric sensibilities with them.

Misþyrming – ‘Endalokasálmar’

Some would say this is the omega. Their quick rise in the last two years was on the backs of this modern classic of a release. To me the live shows are very in your face opposed to maybe the more internal vibes other bands give off. Like most of the other bands, they are working on a follow-up to their debut which I am looking forward to.

Sinmara – ‘Ormstunga’

Sinmara first started off under the name Chao. From the start, they have had their own mission. Recently they have been exploring more melodic ideas, which can be heard here. It’s an interesting departure. Very accomplished musicians. W. of Leviathan, I believe, is a big fan of the drummer.

Wormlust – ‘Sex Augu, Tolf Stjornur’

My own sisyphean expression. The album this track is off was made in a three-month haze. Usually I spend a weekend doing demos but I felt inspired by bands like Vansköpun and Svartidauði to try for a longer experience. Staying awake for the most part of three months isn’t very pleasant for the soul.

Vonlaus – ‘Mystískaos / Vánagandr’

A very recent band, they have a sludge-like, apocalyptic approach which I very much appreciate. I released a tape with them on my label Mystískaos. Since then,I have heard demos for newer material and it promises to be formidable.

Endalok – ‘Englaryk’

Another more recent project, this time opium-drenched. Endalok seems to emanate from an abyssal place that is warped with hallucinogens. This band is about pushing your third eye open with force.

Nornahetta – ‘The Rebis, Spoiled’

Keeping up with the psychedelic theme, Nornahetta improvise all their music under the influence of one thing or another. Each set is the birth of something illicit musically. The material is like listening to trip diaries, a diagram of where the mind takes you when you bend it.

Nyiþ – Live at Oration Mmxviii Festival, Reykjavik, 2018

A ritualistic group that performs under total anonymity. They are an odd one out in that the music is not black metal but dark atmospheres and battered acoustic instruments. But they are an integral part of – even a glue to – the scene since 2012. This one kind of has to be seen and experienced.

Mannveira – ‘Í augum hans sá ég dauðann’

The main theme for these guys is nihilism rather than spirituality which I think can be heard. So more the absence of spirit than its contents. I heard their songs daily on my european tour with them and in sheer brutality they wiped the floor with us. There is that animalistic energy with this band, an urgency.

Svartmálmur, by Verði ljós, is available now from Ditto Press