The Paris Commune failed. For over two months, various leftist factions vied for military and administrative clout within the radical new government of Paris, 1871. Jacobins fought Proudhonists fought Internationalists who all fought the most radical faction: the Blanquists.The Commune was without direction, without leadership, and eventually succumbed to counterrevolution. Raoul Rigault, leader of the Commune’s radical police force, wistfully concluded, “Without Blanqui, nothing could be done. With him, everything.” But, who is this Blanqui?

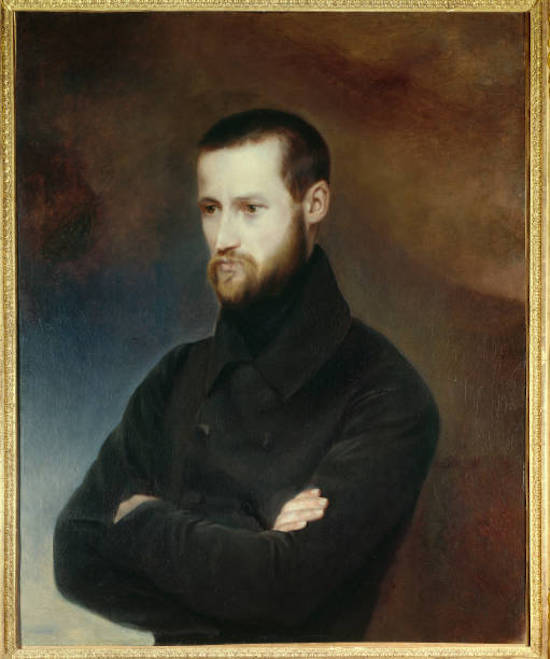

There are two famous portraits of Louis-Auguste Blanqui. The first, painted by his wife Amelie-Suzanne Serre, in 1835, depicts the young revolutionary with arms crossed, eyes aimed outside the frame, a fashionable beard, and a no-bullshit expression hardened from republican revolution and a short stint in jail.

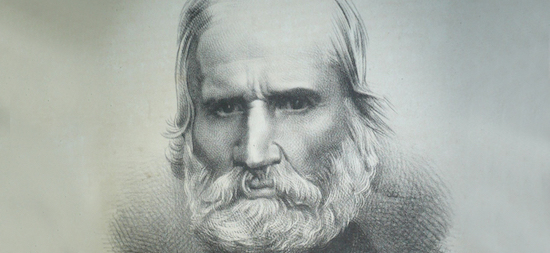

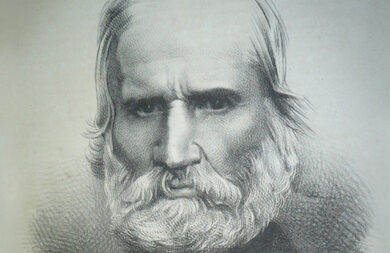

The second, a photograph from approximately 1871, shows Blanqui just as before, only older, more fatigued. The arms: now at his side due to the constraints of his proletarian suit. The beard: fashionable among seasoned generals. The eyes: still transfixed elsewhere. His total time in jail: half his life. He’s no longer angry – he’s confident. By the early 1870s, he had experienced failure after failure in terms of outright revolution, but victory after victory in mobilizing the déclassés. He was no longer looking backward to the republican politics of the French Revolution but looking forward with his own brand of outright communism. If capital was, as Karl Marx painted it, a vampire, here was its Van Helsing.

When reading Verso Books’ The Blanqui Reader: Political Writings, 1830-1880 (eds. Philippe Le Goff and Peter Hallward) front-to-back, the history of the man (and, by extension, a history of French politics of this time in toto) nakedly plays out. How does the naïve brooder in the painting become the personified enemy of capitalism and royalism in the photograph? As Philippe Le Goff succinctly puts it in his introduction, “In defeat, lessons were learned, resolutions were made. The unmaking of a revolution was the making of a revolutionary.” From reading Blanqui’s words, it’s clear that he hardly wavers when arrested – he only, like Thomas Paine and Socrates before him, crouches further into conviction.

But, if Blanqui has been unfairly marginalized as the editors of this volume claim, he must have political convictions different from other leading left-wing radicals at this time, such as Marx, Proudhon, Engels, Bakunin, or Buonarroti? Sadly, those hoping for some sort of Blanquist programme or manifesto will be disappointed – Blanqui’s intellectual project is disparate, his essays short. He never writes about ontology, nor does he seek out a scientific-historical justification for equality.

His brother, Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui, was a respected liberal economist, but Auguste consistently reproaches economics’ grand claim for understanding his people or his world. Instead, Blanqui’s writings unveil themselves as polemical, his values asserted as ultimate good and damn well worth the price of death.

Louis-Auguste Blanqui painted by Amelie-Suzanne Serre, in 1835

The Blanqui Reader catalogues letters, introductions to political pamphlets, speeches (usually on the occasion that he is arrested), short articles, a detailed instruction on how to evade and hold off police during an armed insurrection in Paris, and a long essay on astronomy. Nary a manifesto to be found – the editors label his philosophical writings as “fragments.” However, taken as a whole, Blanqui’s project reveals a thinker and a polemicist with clear ideas and intentions.

First, Blanqui cannot outline his revolutionary ideal without expressing the importance of education. Public education, whether by an official public body or through the work of dedicated journalists and pamphleteers, would be necessary to foster conviction in the people and maintain a regime of the people after the revolution (another key Blanqui fixation after the embarrassing display of non-power by the Second Republic [1848–51] and the relatively easy seizure of power by Bonaparte III).

Here’s a confident passage from a late article “Communism, the Future of Society” from 1869: “Education and communism are so closely linked that one could do nothing without the other – neither a step forward, nor a step back. They have constantly walked side by side at the head of humanity and they will continue to do so until their common journey is complete.” And a grave warning, a few pages after: “Communism will arise inevitably from generalised education, and it can arise in no other way.” That’s an older Blanqui, now comfortable with the “communist” label after much internecine squabbling; but, here he is with jejune republicanism (“Equality Is Our Flag” in 1834): “…it is through intelligence alone that it governs [men] and that it leads them to coordinate their efforts towards a common goal, which is the well-being of all.” His revolutionary slogan? In the same article it is “Intelligence and labour!” Even when engaged in his conspiratorial networks (which would later be the basis of organizing for terrorist cells), his initiation ceremony includes the initiate to proclaim: “Like the body, this intelligence has the right to life, and thus the right to education is simply the mind’s right to existence.”

This emphasis on education and its natural place in the ever-coming revolution even outlasts Blanqui’s love for conspiracy and armed uprising. As Le Goff notes, “Upon his release in August 1859 following a general amnesty, Blanqui quickly decided that propaganda and clandestine political publications, rather than conspiratorial action, would provide the best means of sustaining and renewing a revolutionary project in the face of widespread resignation.”

This hits upon another of the Blanquist takeaways, and one that aptly compares him to Lenin or Castro: if you don’t know what you’re doing, your armed insurrection is nothing but petty revenge, a squaring of the debts of injustice. The uprising must know what it’s fighting for, what it’s fighting against, what time to best strike, how to organize the proles, exactly how to defeat those in power, and how to maintain power once successful.

But who, exactly, is to do the work of educating? Who maintains power? The answer is sure to be upsetting to the modern leftist who would acquiesce power to those most disadvantaged: Blanqui claims that the déclassés must do it. The bourgeoisie who hate the bourgeoisie must lead. In “Work, Suffer and Die (c. 1851-2)”: “Without this sacred battalion (the déclassé bourgeois), indefatigably rallying the masses in the wake of every rout, the latter would have long since slumped into servitude. Through their heroic tenacity, the resolve and constancy of this small troop saves the masses from discouragement and despondency.” Blanqui comes to this conclusion through experience; farmers and other proles were quick to support the coup by Bonaparte III after witnessing the weakness of the Second Republic (mainly thanks to leftist infighting and plenty of concessions to the previous governing class). However, just a paragraph later: “Now what is the watchword inscribed on its banner? Democracy? No! Proletariat: for the soldiers are workers even if its leaders are not. Doctrines, interests, passions – they all come from the people.” Although the bourgeois have had enough free time to educate themselves in philosophy, military tactics, history, and leadership, the revolution ultimately belongs to the proletariat, the sansculottes, the Hébertists, and must turn power over to them after a provisional government has worked out all the kinks.

However, this provisional government may fail. In Blanqui’s lifetime, any successful revolution always gave way to an élite unprepared for power, incapable of setting up a political platform, and and quick to lick the boots of liberals, conservatives, even royalists. Blanqui grew up under the crown of Napoleon and the return of the ancien régime – the Bourbon restoration. He saw the July Days riots of 1830 turn this Bourbon monarchy into a Orléanist monarchy, hardly a victory for his republican comrades. The revolution of 1848 does establish the Second Republic, but it only lasts for three years. When Bonaparte III surrendered to Bismarck in 1870, the Government of National Defence showed promise in exhibiting republican values. However, this Third Republic’s Adolphe Thiers ordered the experiment of the Paris Commune to be stopped, the more radical elements shot. Every time a revolution succeeds in Blanqui’s lifetime, the more conservative elements climb to the top and any promise of revolutionary upheaval is blocked. What went wrong?

Blanqui, c.1871

This proves to be what Blanqui’s biggest bugbear. Any revolution can succeed if you muster enough force at the right time, so why does this never translate into a formidable government? When Blanqui writes about the massacre in Rouen, he calls for the provisional government to claim responsibility or be seen as counterrevolutionaries: “It is a royalist insurrection that has triumphed in the ancient capital of Normandy, and it is you, a republican government, that supports these rebel assassins! Is this treason or cowardice? Are you cowards or accomplices?” In his “The Union of True Democrats” he casts his cadre of socialists as the true radicals compared to the Second Republic: “There must be nothing in common between the faithful socialists, the proven defenders of the people, and the henchmen of this Provisional Government, of this executive commission, the disgrace and scourge of the revolution.” And, in his angriest text, “Warning to the People,” written during the Second Republic’s collapse: “Treason! [The Provisional Government] attacked the workers of Paris on 16 April, and imprisoned those of Limoges; it gunned down those of Rouen on 27 April; it unleashed all their executioners; it deceived and hunted down all sincere republicans. Treason! Treason! It and it alone must bear the terrible burden of all the calamities that have all but wiped out the revolution.”

Blanqui pulls this No-True-Scotsman argument frequently: only the most radical Blanquist communism must rule and anything stinking of moderate republicanism will eventually (if not immediately) act as Judas to the people. And yet, full of contradictions, he often denounces this sort of petty communist infighting as a deathtrap to revolutionary rule. Only unity can sustain the people. From his letter to Maillard: “The Proudhonists and the communists are equally ridiculous in their reciprocal diatribes, and they do not understand the immense benefits of doctrinal diversity.” A little earlier: “The doctrines no doubt disagree on many points, but they work toward the same goal, they have the same aspirations … . [their result] has nonetheless taken hold of the spirit of the masses; it has become their faith, their hope, their standard.”

Blanqui advocates for the revolution to come soon – immediately – for any programme will be better than the current injustice. However, he also advocates for deliberation, for a well-timed strike, for patience lest the revolution fail. He swears by his communism as the only correct revolutionary doctrine, yet clamors for leftist unity at all costs. These aren’t quite contradictions, but it’s easy to see why there is no unified Blanquist manifesto.

There are plenty more Blanquist concerns. Blanqui consistently denounced Auguste Comte’s Positivism for its call to inaction. After all, if one genuinely believed that the spirit of history would naturally lead to more progressive societies, why pick up a gun and risk jail time or death? Blanqui gives a good quip in a review in 1869: “The fait accompli has an irresistible power. It is destiny itself. The mind is overwhelmed by it and dares not rise in revolt: it lacks a solid foundation, and can support itself only on nothing.” No, after all, “True morality is active.” Pick up a gun, meet in the streets, take power, keep power.

Blanqui saw through his many defeats that without constant vigilance and insurrection, the royalists will simply take more and more from the people. Fatalism is fatal. Blanqui also cared for science and hated the church, members of which he termed the “black army” (think Catholic clergy attire). He asked his comrades to not drink so much beer at political meetings. He cared for his wife who died at the age of twenty-six. Her death wrecked him. And, in case one thinks that his love for the people was not genuine, 100,000 attended his funeral march. The Blanquists, his followers, would die out shortly thereafter, most ideological inheritors then turning to an early fascism by the early twentieth century. His name would be locked away in the penumbra of libraries, mentioned only by those interested in the marginalia of history.

Yet, Blanqui is with us. Note the fear of left-wing re-education in American universities. Note Ronald Reagan’s legislation of gun control once the Black Panthers start arming low-income black communities around Los Angeles. Note the glee commentators take in pointing out that well-off young intellectuals (the déclassés) often lead grassroots communist movements. Marx put it best: “the proletariat rallies more and more round revolutionary socialism, round Communism, for which the bourgeoisie has invented the name of Blanqui.”

Although his name is no longer mentioned, Blanqui’s particular brand of communism is the one that modern-day royalists still fear, that modern-day liberals still distance themselves from. If there were any corporeal form that Marx and Engels’s spectre of communism could inhabit, it would be that bearded Van Helsing, imprisoned, ruminating on his failures, ready to strike again.

The Blanqui Reader: Political Writings, 1830–1880 by Louis Auguste Blanqui, Edited by Peter Hallward and Philippe Le Goff, is published by Verso