In a 1960 interview for the BBC series, Picture Parade, Alfred Hitchcock famously stated that “Drama is life with the dull bits cut out.” It seems to be a dictum that the director followed throughout the majority of his career, heightening the stylised end of narrative story-telling in film to arguably its highest levels of innovation. Yet, in Hitchcock’s most renowned and respected film, Vertigo (1958), the usual snappy running length of the director’s cinema is extended, to the point where it is obvious that something more is happening in its quiet scenes; moments that, in most other examples of his film work, would be cut or shortened.

Based on the novel by French crime writing duo Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, Hithcock’s film uses slower scenes to extend the growing obsession of its lead protagonist in a variety of interesting ways. Whether through long takes or placing the job of thematic development on the score by Bernard Herrmann, Hitchcock beautifully films everyday moments in Vertigo in a way that he rarely ever did before or after.

Vertigo follows a police detective, Scotty (James Stewart), who is called in to help an old friend, Gavin (Tom Helmore), discover the reason behind the increasingly strange behaviour of his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak). Believing her to be possessed by the spirit of an ancient, suicidal relative, Scotty’s tailing of her slowly turns into an obsessive love. He makes contact after she attempts suicide in San Francisco Bay, before beginning a doomed affair with her.

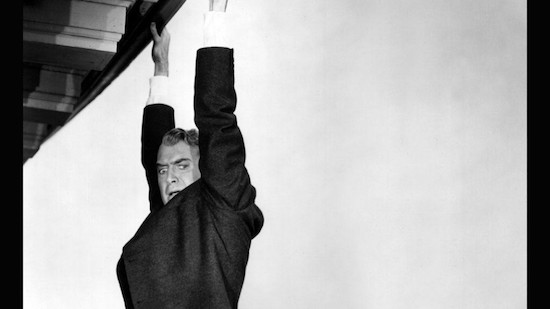

All is not to end well for Scotty and, reminiscent of when a policeman was left to die from falling from a building due to the detective’s acrophobia, she succeeds in taking her own life by jumping from a high church tower before he can reach her in time to save her. But nothing is what it seems in Hitchcock’s film. When Scotty, after suffering from psychological torment of his guilt, finds Judy, a woman who suspiciously reminds him of his lost lover, the traces of a conspiracy begin to show.

Hitchcock extends Vertigo chiefly with driving sequences. There have always been sequences of characters getting from place to place in his films and they have often served a purpose. In Psycho (1960), Hitchcock condenses the first segment of that film’s narrative over its driving sequences rather than extend the film and show them separately. The escape of Marion (Janet Leigh) is overlaid with other characters’ realisation that she has stolen money.

Similarly, in North by Northwest (1959), a film famously built on the desperate journeying of a chase, driving sequences often have a purpose rather than being simply perfunctory: in this case, the potential murder of its lead character, Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant), at the hands of the film’s enemies – as well as isolating the lead to heighten the danger.

On the surface, Vertigo’s early driving segments don’t seem to do anything like this. They are part of the character’s job and have a purpose but that purpose is never reduced down into simple key notes but actually shown in great detail.

The first half of the film is littered with driving sequences and is largely made up of two tailing segments where Scotty follows Madeleine to a variety of locations. In the first of these, he follows her in her distinctive green Jaguar Mk. VIII to a flower shop, a graveyard, a gallery, and a house that she appears to be secretly renting before mysteriously losing her entirely. All of these locations are essential to both the characters’ and film’s devious scheming as it adds to the supernatural belief of the narrative and ignores any potential rational explanation for what seems to be happening. But the way Hitchcock lingers in these scenes is interesting. There are multiple compositions that show the road ahead from Scotty’s car, Scotty looking towards camera and then cutting out to show both cars making various manoeuvres. On paper they’re exactly the sort of everyday moments that Hitchcock has previously removed or condensed to some basic narrative bridge and their repetition leads to the evolution from tailing to stalking.

Here, the scenes build Scotty’s obsession slowly but meaningfully. In fact, it’s hard to imagine believing in his growing obsession without the slow burn of his meticulous following. The film will in many ways be one long pursuit of this woman though the journey will never reach a comfortable conclusion. It’s one of the weaknesses of the original book which tries to grow the character’s obsession with too little emphasis on the monotonous process of his job in following Madeline. The scenes in the film are meticulous, the colours and lighting are perfect as is Stewart’s performance. But it is Bernard Herrmann’s score that is slowly building in evidence of a burgeoning affection. As the composer famously said in an interview with the musicologist Royal S. Brown, “[Hitchcock]only finishes a picture 60%. I have to finish it for him.” The motifs that are smuggled into the score over these scenes find their way later on into some of the film’s more amorous moments. There’s almost a sense of déjà vu when love is properly and finally declared for real. Certain fragments of musical score, working in a much more subtle way than the typical leitmotif, eventually build into what is the love theme. This only comes to full fruition on Madeline’s rebirth when Judy has been discovered and forced into becoming the dead woman. Her morbid transformation or return, however, was foretold when she was earlier behind the wheel.

There’s a beautiful sense of ghosting throughout the film because of this cinematic extension: a ghosting of Madeleine by Scotty on the job, a ghosting of a literal quality of Madeline restepping the life of a supposed dead woman, and the eventual ghosting of a love to be lost twice over. The rare sense of the everyday journey finds its way into Hitchcock’s film, not just because it’s necessary to the workings of the narrative. It is because these places and moments are when the most dramatic of yearnings can first arise. The eventual destination may only be a tragic circle. But the road down to San Francisco Bay seemed straight at the time.

Vertigo is available on screen and on demand