Writing about the past is a free hit. You don’t have to risk anything. You know how it turns out.

At any rate, you used to think so.

Lately, I’ve been unable to read books or watch documentaries about recent European and American history with the same dispassionate fascination I once did. The comfortable sense I had that its worst horrors were safely in the past, its best lessons well learned in the present, has dissolved into vapour, into anxiety – into, often as not, dread.

Yet at least, when it comes to the past, popular culture, popular music, remain solid enough. When, for instance, I settle down to begin one of these anniversary pieces, I invariably have a clear picture in my mind of what my subject is, what it stands for, where it fits. This will invariably alter in the writing, as it should; but I know where to begin, and I will discover where to end.

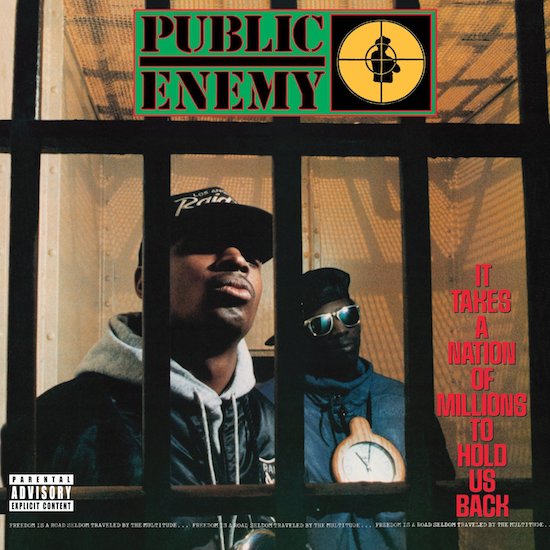

Not here, though. Not with this one. For so many reasons. And those reasons are intimately and intricately connected both with the greatness and the significance of the work at hand, and with the grotesque and straight-up terrifying state of things. In particular, the state of the nation of millions. It’s a damn shame that Public Enemy’s second album still matters so much. Or at least that it still matters so much in the way that it does. Chuck D indicated as much to tQ on the record’s 20th anniversary: “Yeah, it’s [still] radical politically. The message is radical today because it’s not really being said a lot. You want it to not be radical, but it is…” On the face of it, what Chuck D meant is that it remained radical within hip hop, because radical hip hop remained relatively scarce: “…because it’s totally different from Soulja Boy,” is how he concluded that thought. There is another, broader and equally applicable interpretation, which is that you wanted it not to be radical because you wanted radical hip hop, 20 years on, to no longer be such a necessary and urgent reaction to the way things are. That, 20 years on, It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back should not still have been so applicable to the lives of black Americans. That the long arc of the moral universe, bending towards justice, should have rendered its righteous fury redundant; should have relegated that aspect to its own time, left the record to be valued for its stunning artistry.

And that was ten years ago. When America was months away from electing a black president. On its 30th anniversary, Nation Of Millions feels even more relevant than it did then. Perhaps even more relevant than it did in 1988. As much as that testifies to the album’s brilliance, it testifies even more to the abysmal realities of 2018.

In making Nation Of Millions, PE set out with the conscious aim of making their own What’s Going On – an album that, in keeping with their conception of rap as “the black CNN”, would communicate both widely and directly with black America; that would echo Marvin Gaye’s “Talk to me” plea not only in taking it to the streets, but taking it from there in the first place, acting as a conduit, a means to cohere, articulate, analyse and disseminate that reality.

They far surpassed this ambition. Which is not to say that Nation Of Millions is necessarily the better album – although as a political piece, and a polemical one, it is in another league, one of its own making. Rather, that they created a new category; a thing that was sui generis. Nation Of Millions was not an updated or even upgraded version of something else. It was something else. Nobody had ever heard anything like it, because there never had been anything like it. PE approached hip hop as science, and made it into astounding art. As it goes, PE’s next album, Fear Of A Black Planet, would come much closer to being a rap iteration of Gaye’s record. It also happens to be my favourite album of theirs, the one I find most musically satisfying as a whole; but there is no question in my mind that while Black Planetis also a masterpiece, Nation Of Millions is much their most radical and important work. I can think of no rap albums that could challenge it on those counts, and very few of any other genre, either. It is one of the indisputable peaks of popular music.

To understand how Nation Of Millions became what it was, it might help to start with what Public Enemy themselves were. If you go to see PE today, you’ll find a first-rate showband arranged around the remaining duo of Chuck D and Flavor Flav. Which is enormous fun, and also very far away from the group’s origins. PE did not conceive of themselves – or perhaps it would be more accurate to say PE, the collective, did not conceive of itself – as a hierarchy of priorities, or a musical core with additions bolted on. It conceived of itself as an organisation constructed to fulfil simultaneously a host of equally necessary functions. PE was a device of interlocking parts. All its components – the MCs, the production team, a security crew doubling as a stage act, a “Minister Of Information”, a “Media Assassin” – were vital to its operation. Granted, some participants might be more interchangeable than others, but the roles were all essential to delivering the message. Indeed, not just to delivering a message, which any paperboy or postman could do, but to driving home a message. Public Enemy set out to be unignorable, and by Christ did they succeed in that.

Nation Of Millions was put together the same way the organisation itself had been. It wasn’t simply a matter of setting beats to rhymes, or vice-versa. Like the band, it was an entire machine that had to be assembled, with both fierce commitment and meticulous care, to do a job. They had in mind not only what the album itself would be, but how they would perform it live; to which end they agreed it needed to move relentlessly and at breakneck pace. It opens with a recording of the band being introduced onstage at Hammersmith Odeon: what follows is, it is implied, a show in itself. It might be very far from a live recording, but it is very much an alive one. It is intended to feel as if it’s taking place onstage in real time before your eyes as well as your ears.

Sometimes great records result from a singular vision, superbly realised (or even mis-realised, but with wonderful results). At others, they result from the happy situation of having exactly the right combination of talents to bring them about. Nation Of Millions is the Platonic ideal of the latter. Effectively, it was created by six people: Chuck D, the lead MC; Flavor Flav, the hype man and holy fool; the members of The Bomb Squad (Hank and Keith Shocklee, Eric Sadler – Chuck D was also credited as “Carl Ryder”, and Bill Stephney as production supervisor); and DJ Terminator X. Chuck D’s voice was the central element, as it had to be: when you have at your head the most powerful and authoritative MC anyone’s ever heard, you’re going to make sure people do hear him. Hank Shocklee, foreman of The Bomb Squad, famously and unimprovably described his intention as making “the voice of God” emerge from a “thunderstorm of sound”.

Hank Shocklee’s peers are not so much the other great hip hop producers as they are the likes of Brian Eno and John Zorn. Chuck D has described him as a “daredevil” and an “antimusician”, and it’s hard to overstate the importance of this to Public Enemy’s magnum opus, which is as magnificent a work of sustained antimusic as any I know. The obvious sources for PE’s sound, as for so much hip hop, may be James Brown and fellow masters of the more rhythm-centric school of funk and soul. But the spiritual forebears of Nation Of Millions are the hard-boppers, the avant-garde- and free-jazzers; artists with the imaginations and the chops to detonate black American music and reassemble the atoms into novel and shocking forms. What PE had that those artists did not was access to a sudden onrush of revolutionary technology that allowed them to turn the means of recording into their most significant instrument. If anyone has ever capitalised more brilliantly on such timing and opportunity, I can’t think who.

The other Bomb Squad members were variously skilled at creating rhythm, feel and movement, using vocal and instrumental samples as riffs (while Flavor Flav played the drum machine track on ‘Rebel Without A Pause’ by hand, giving it a live rather than looped feel; Liam Howlett of The Prodigy later incorporated that kind of variation into his programming to similar effect.) Hank Shocklee’s gift, or one of them, is his ability to hear and arrange things in a mode that is not, to use his own term, “linear”. One of the most extraordinary things about Nation Of Millions is the way everything seems to happen at once. Not just the density of the sound, which is itself astonishing, but the baffling, jaw-dropping, pulse-quickening juxtaposition of chaos and coherence across the whole album. If one thinks of it as a machine built for a purpose, at times it seems that purpose is, as with Jean Tinguely’s mechanical sculptures, to destroy itself in the most spectacular fashion imaginable. But at the end, the work remains intact and it’s the audience that’s in pieces.

A run-through of the tracks feels redundant here. Nation Of Millions is one of the founding documents of contemporary left-field music and its associated sensibility; there can hardly be a reader, a writer or indeed a subject of tQ who is not closely familiar with it. It contains a clutch of tracks – one hesitates to call them songs, because the word doesn’t seem adequate to describe them – which one automatically files among PE’s “hits”: ‘Bring the Noise’, ‘Don’t Believe the Hype’, ‘She Watch Channel Zero ?!’ All of these are incisive, punchy, and feel shorter than they are. But the track that has over time become most emblematic of the album is the extraordinary ‘Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos’, a title which not only summarises its story, but also encapsulates its sound. (It bears noting here, too, that Nation Of Millions was intended to run for almost exactly one hour.) It’s an anomaly on the album as a whole, slower and sprawling, thumping and twisting, almost a blueprint for their next LP but one, the super-heavy, much underrated rap-rock piece Apocalypse ’91… The Enemy Strikes Black. Yet its narrative cuts right to the heart of the theme on Nation Of Millions, as so concisely captured in the album’s own title: the intrinsic alienation of black Americans from the country in which they live. It is a fantasy, but not an implausible one, of unjust imprisonment, escape and guerrilla warfare. It could be the story of Muhammad Ali’s run-in with the draft, expanded to a more modern nightmare, and its essence is certainly to be found in the phrase misattributed to Ali (although he may well have shared the sentiment), that “No Viet Cong ever called me nggr.” That is, it categorically rejects the claim upon a black person’s loyalty and service of a country that structurally oppresses that person, and all of their race.

All? Well, that depends on who you ask. Martin Luther King Jr’s dream was that black people would become equal citizens of their own country, and it was towards that end that the liberal impulses of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society were directed. With civil rights on the one hand, and economic progress on the other, surely equality was only a matter of time. It is a bitter lesson when the letter of the law is at last wrested towards fairness, and prosperity (at least to some degree) comes your way, yet equality remains a mirage. 20 years on from King’s assassination, PE might have been seen as pessimists, or at least extremists. True, black people were disproportionately represented among the poorest; but was there not now a burgeoning black middle class? (There was.) Did the nation’s laws not forbid the discrimination King had led the fight against? (They did.) There was that arc of the moral universe, duly bending. Who knows, maybe in another 20 years America could have a black president. (It had.)

So much for the pessimism; were PE not just fighting yesterday’s battle? As for the extremism, well: PE were overt black nationalists. Their figurehead, it was once noted, seemed never to have met a conspiracy theory he didn’t like. They championed Louis Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam leader whose noxious anti-Semitism (still prevalent in radical and black power movements today, where, for instance, his poisonous lie that Jews were the principal financiers and beneficiaries of the slave trade remains in circulation) would soon be publicly echoed by PE’s “Minister for Information”, Professor Griff.

The irony is that Jewish people could have told black people this: it doesn’t matter whether you climb the ladder economically and politically. If you belong to a race of which there is widespread, deep-rooted, longstanding fear and suspicion, it will never go away. It’s always there lurking, festering, waiting until conditions favour a resurgence. (Many Jewish people had themselves succumbed to the delusion of security at that point, which would bring its own bitter lessons. But that is another, parallel story.)

And now, 30 years on, with an American president overtly supportive of white supremacism, and a Black Lives Matter movement that, whether or not one agrees with specific politics of its leadership, is unquestionably born of dire necessity, the idea the Public Enemy were overly pessimistic is liable to induce mordant laughter. If anything, it feels as if they understated the matter. America is a country in which even its wealthy black citizens understand very well that their skin makes them – literally so – targets; that it puts their children in jeopardy when they walk down the street; that status is no protection from threats supported and often inflicted by its institutions.

In its themes and its rhetoric, Nation Of Millions prefigures the thesis of Ta-Nehisi Coates, in his book We Were Eight Years In Power, that slavery is America’s original sin, and can never be eradicated; that white supremacism is not an aberration to be eventually fixed by progress, but a structural foundation that will persist for as long as that structure does. The American Civil War paid for slavery in blood, yet the debt remained unsettled, because the compact America struck with its white citizens is that, no matter how low they sunk, their birthright would raise them above the nation’s black population.

Coates’s writing on race in America has a despairing, nihilistic tone, originating in those deep, dark waters where weariness meets rage. The same may be said of ‘This Is America’, the horrifying and (in every meaning) sensational tour-de-force song and video with which Donald Glover, as Childish Gambino, delivered such a shock earlier this year. Yet Glover is not PE’s direct heir. ‘This Is America’ is a righteous gonzo howl hurled into the internet bearpit that is contemporary American culture. PE, working in the pre-wired days, sought to create their own communications system. Their fury was more than matched by their focus. Nation Of Millions could probably have happened only exactly when it did: at a moment when technology permitted its creation and did not yet make redundant its conceptualisation as both medium and message; and when Western societies by and large abided by the idea that overt racism was somehow distasteful, and unrespectable – meaning its better disguised forms required intense scrutiny. All bets are off now, and polemical art feels like so much shrieking into a hurricane. Which is no reason not to do it, but every reason to think it can’t possibly have the impact for which PE plotted Nation Of Millions.

There it is, then. The greatest, really the only thing of its kind, and one of the greatest things of any kind. And here we are, sliding down the chute to Hell, with those at the forefront braying to the rest of us, dragged behind them, that paradise waits below. What so many black people have long known about the world, perhaps the rest of us are about to discover. Where nations of millions turn upon one or another race, they will inevitably turn upon themselves.