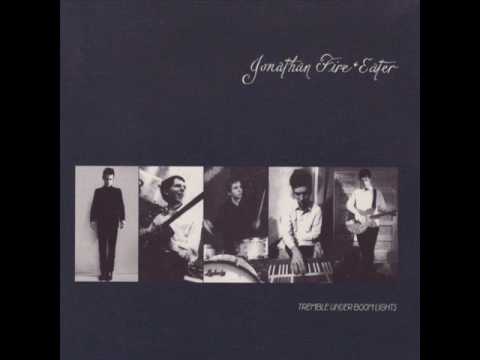

Bands that show indescribable promise, deliver on it for a brief moment, then spectacularly implode are a dime a dozen in rock & roll, but few of their stories are as dramatic, intriguing and, ultimately, as tragic as Jonathan Fire*Eater’s. This brilliant group of childhood best friends from New York, via Washington DC, went from being perhaps the most hyped American band of the mid-90s, signing a million dollar contract with David Geffen’s DreamWorks (the label’s launch band), being courted to model for Calvin Klein, then totally self-destructing three years later. It seems almost impossible to imagine but, according to their publicist at the time (a former professional dominatrix called Erin Norris), the band held a meeting before the release of their major label debut, 1997’s Wolf Songs For Lambs, to request that sales be halted at 500,000. For a number of reasons, not only because it was their least immediate recording, it ended up selling somewhere between 7,000 and 12,000 and has long, long been out of print. The two records that preceded it, ‘The Public Hanging Of A Movie Star’ EP from 1995, and 1996’s mini album, Tremble Under Boom Lights, are also lost to time, despite being responsible for all the fuss, and understandably so: the blueprint for the New York garage rock explosion that The Strokes would end up leading five years later can be found in those eight short songs. It’s not fair to say The Strokes wholesale ripped Jonathan Fire*Eater off, but they’re indebted and are the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Interpol.

The tragedy in Jonathan Fire*Eater’s story concerns their snarling and literary frontman, Stewart Lupton, the band’s bona fide star. Three other members (organist Walter Martin, guitar player Paul Maroon, and drummer Matt Barrick) went on to form The Walkmen with Hamilton Leithauser and Pete Bauer from The Recoys and make a career of music. Stewart, whose on-off battle with heroin was cited as a primary reason for Jonathan Fire*EaterEater’s collapse, performed for a while as Stewart Stephenson with his friend Judah Bauer from the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, then fell totally off the radar. He quickly turned into a mythologised figure. "Whatever happened to Stewart Lupton?" became an often-posed question in internet fan forums, and with no one able to provide a concrete answer, an appalling rumour began to spread: that addiction had killed him.

Stewart Lupton, though, is not just another example of a super talent who pissed his chance up the wall. Unsurprisingly, when he found out about his supposed demise he plotted something of a comeback. First thing, he posted a message online saying not only was he alive, he also had a new band together called Childballads. Simultaneously and coincidentally, James Oldham, formerly of NME, huge Jonathan Fire*Eater fan and boss of Loog Records (home of The Horrors, Patrick Wolf and The Bravery) had himself been Googling Stewart’s name to try and find out where he was. He stumbled upon the post, tracked him down and suggested putting a Childballads record out. That was 2005, seven years after Jonathan Fire*Eater split. It took till March 2007 for the folksy six-track mini album to arrive and, best of all, it wasn’t just good, it was exceptional. "I keep hearing talk of the doom and they’re sending the meek home," the title track begins, revealing, "But that ain’t half as bad as the shadow that’s caught in the hollow of a cheekbone."

Stewart even returned to the UK for the first time in almost a decade, playing an impassioned Childballads show at London’s Metro Club on April 30 to a shockingly small number of people (about 30), followed by a Cat Power support slot the day after and a few dates in France. The band have also performed headline gigs in the US and have been guests of Interpol and the Fiery Furnaces. Against all the odds, it seems this most wild and intelligent artist, still only 32, is officially back on the road. He’s flat old-fashioned broke and the drugs haven’t been left behind yet, but he’s giving it another shot and, creatively, he’s currently well on top of his game.

That Stewart Lupton could have been as big a star as Julian Casablancas, and still could be, is something for him to muse about and he admits to sometimes doing so. Both exhibit a detached cool on stage and the parallels don’t stop there. There are strong similarities in the sounds of Jonathan Fire*Eater and The Strokes and all their members were privately educated. Jonathan Fire*Eater attended St. Alban’s School in Washington DC (former Vice President Al Gore, himself a Senator’s son, is an alumnus too) before moving to New York where they lived a double life of studying at some of the city’s renowned universities and falling over each other in a shit-hole two-bedroom apartment in the then-dangerous Lower East Side. They practised in a boiler room in a basement at Columbia University, where three of the five were students. It was there that they discovered their sound. When they took it to the clubs, the band, and particularly Stewart, caused near pandemonium. As fans remember it, Stewart would bound on stage after a brief instrumental introduction, then deliver his lyrics with "fever" and a trademark "death grip on the mic stand".

"Right now the record companies are sort of circling like vultures," said Stewart in 1996, soon after the release of Temple Under Boom Lights. The three-album million-dollar deal they eventually signed with DreamWorks was an unusual one: they were to keep full creative control and, most brilliantly, their nearly toothless manager was to get a full set of new gnashers. The press enjoyed that far more than the fact they refused to make a video for their debut major-label single and were reluctant to do interviews with magazines they thought were lame. They were accused of arrogance and self-obsession by journalists, who gleefully sharpened their knives to review what would end up becoming their first and only album for DreamWorks. "Loudest buzz, but little real-life bang," the Los Angeles Times wrote in December 1997. By July the next year, Jonathan Fire*Eater were over. Distraught and in ill health (he was reported as being "absolutely fucked out of his gourd" during their 11.30am Glastonbury performance that June), Stewart returned home to his parent’s house in Washington DC. He certainly hasn’t been completely out of it these past years – he enrolled at George Washington University to indulge in his life-long passion for poetry and he learnt to play guitar – but perhaps this message on The Walkmen’s website forum says it best: "I went to college with Stewart Lupton in New York, and lived down the hall from him. He used to sit in the laundry room at 4am typing on this ancient typewriter. He was a real presence no matter what he was wearing, or doing. I figured he’d probably become fantastically famous, and drop dead of a heroin overdose before 30. Fortunately, the latter never happened. Sadly, neither did the former."

Hello Stewart.

Stewart Lupton: Hey, how are you? Good morning… um, what time is it there?

Quarter past six in the evening.

SL: Happy sunset!

Where are you?

SL: I’m in a pick-up truck with my friend Carole, my lady friend, and we’re going to spring her 17-year-old badass son from a shitty boarding school in upstate New York. A very covert mission. And I’m gonna stop by New York and see the band, hang out for a bit, maybe go to a museum or something. We’re gonna stay in one of these hotels that have been erected in the last five years in the neighbourhood where my old band used to live in the early 90s before Giuliani cleaned it all up [the Lower East Side]. They overlook the tenements where there used to be chicken fights on the roof and eight drug dealers per block. They’re nice hotels but I feel like I’m betraying my roots or something [laughs]. There used to be nothing around there other than fortune telling ladies with no customers. Now there are Asian fusion restaurants and little waterfalls and stuff like that.

It seems you’ve intentionally left a lot of space in the Childballads music, at least compared to Jonathan Fire*Eater. I think you called it ‘roomy’ and ‘warm’.

SL: Exactly. If you don’t really have finality, then you can’t be judged [laughs]. We got this review from The Guardian after we played a show at the Metro bar in London – our first show as the new band, the guy forgot to mention – saying that they were basically like a bar band. I thought that was great. I don’t think they were that happy about it, but there are all these fucking bands on MySpace clambering to have their own identity, like The Horrors or The Hives or whatever, and I like it that my band is kind of anonymous. It’s just chords – Paul doesn’t play a single lick. He has another band called Beaut and with them, because they’re only two people in the band, he does all these amazing loops and effects. The time is coming when we’re gonna start weaving some of that into what we do but, so far, it’s just been chords – an anti-style. By the end of the European tour there was definitely some personality leaking out, but right now we’re just concerned with trying to be a band, getting the changes right and feeling good on stage. It’s nice not having a girl in the band and dealing with three guys [laughs].

The second show you played was supporting Cat Power at The Forum, also in London, the day after. How was that?

SL: Fantastic. We played really early but it was at least half full. I got really emotional because playing in 2,500 capacity theatres was kind of where I left off 10 years ago. We were almost at that stage. And, to be honest, that’s my life’s goal – my life’s dream is to get to that level again. I don’t want to get any higher – I don’t care about MTV or any of that stuff – but to be able to fill beautiful theatres that size, metaphorically and literally, would be very satisfying. The most comfortable I felt on the whole tour was playing there. I arrived early, walked around on the lip of the stage and I loved it. There’s a formality and respect about theatres like that. You go to these fucking little dingy-ass nightclubs and what’s the aesthetic? Black? There’s something about theatres and town halls that’s handed down. You really have to hone your mind to think about it and realise what it means, because it means a lot.

You’ve been playing a Bob Dylan song in your set, ‘Walls of Red Wing’. Has he been a big influence on your new music?

SL: I guess so, but I play it down now because the fucking Walkmen have all of a sudden become Dylan-esque. I’ve been obsessed for a long, long time, but I’m trying to get over my obsession and be a bit more, er… I’m not a record freak anymore. I don’t know.

So you feel a sense of rivalry with The Walkmen?

SL: I used to say there wasn’t a rivalry with The Walkmen, but I got back to New York feeling elated with my new bandmates and our success on the tour – it was a really surreal thing because I hadn’t been to Europe for eight or nine years and I finally made it back behind British microphones off my own steam – and there were fucking Walkmen posters everywhere, and fucking huge ones too. You know how they do those posters on buildings that cover windows up and they pay the tenants? I always wanted that because I thought it would be a great way to make rent… Anyway, they had these posters up in New York for the Flaming Lips and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and The Walkmen. They did a tour promoting Camel cigarettes too – eight-date tour on the east coast – and they got 20 grand a show. Fucking ridiculous. These are the same people that had this pseudo-Fugazi, five dollar X on the hand, church basement righteousness and turned down Calvin Klein, which I wanted to do and frankly I think is a little bit cooler than doing a song for the Spider-Man 3 soundtrack. So the answer to your question is, ‘Yes, I’m ready for a full-on rivalry with The Walkmen.’ They’re really starting to piss me off. Can you print that in capitals?

Sure. STEWART LUPTON IS READY FOR A FULL-ON RIVALRY WITH THE WALKMEN BECAUSE THEY’RE REALLY STARTING TO PISS HIM OFF. But aren’t you just jealous?

SL: I’m jealous of the money and nothing else. I could do what they’re doing in my sleep. I already did that. I respect their work ethic but their music interests me about as much as the New Jersey Turnpike. It’s as bland as the New Jersey Turnpike. I actually liked the Bows & Arrows record but I really don’t think the whole Walkman thing is any good anymore. I feel great! I’ve never said anything like this before. You’re gonna get an exclusive [laughs].

Do you ever see them?

SL: We’re cordial, but there’s tension and there always will be. I’m jealous of the money. I’m a writer and a poet and there’s not a lot of money there. And I’m jealous of the fact that they have a fucking manager, and a van. In fact, they probably have a bus. But I’ve already passed them artistically with this new EP so I don’t sweat too much at all. It’s not hubris, it’s just objective empirical reality. The first thing I did after Jonathan Fire*Eater broke up was this country acoustic thing with Judah – it wasn’t country, more, I don’t know, folk – because I was really into the five-CD Dylan Basement Tapes box set and some other folky records. I was so fed up with the screeching fucking doorbell organ we had in Jonathan Fire*Eater and the preciousness of it all. It was so impersonal. I’m happy with the way things are now. Artistically, I sleep fine.

So you were relieved when the band broke up? I thought it upset you deeply.

SL: I was fucking destitute. The thing I did with Judah was eight or nine months later. The band breaking up was the final blow: my house of cards came down and the world gave me an ass-whooping that became one in a series – the anthology of kicking the shit out of Stewart Lupton started then, then it reached volume eight, and it’s abated for the moment but there’s still some tension between me and the world. So, yeah, I was torn up – we were best friends and I was an only child. I met Walt when I was seven or eight years old – the second day after I moved to Washington DC from South Carolina. We were inseparable. What we talked about doing when we were 15, we did. How could I not have been upset?

It seems when the band did get together and moved to New York, you were super ambitious. You knew you were good and you wanted fame. Is that right?

SL: Hell yeah! But there’s a difference between ambitious and preciousness and hubris. And there’s false humility, arrogance, narcissism, and knowing whether you’re good, and we knew we were good. Where’s the bar? Was it other bands? No. We never thought about ourselves in relation to other bands – just whether we could make the hairs on the back of the neck stand up. We’d stumbled upon this sound and it was like splitting the atom for us – a big discovery. I remember the series of practices – the two or three when we uncovered our identity, sonically. It was exciting, but, you know, er, that’s a novel…

Do you still feel the same ambition?

SL: Definitely. I admire that about The Walkmen too, but they don’t have it anymore. It’s a slow burn and they should just quit. They don’t have the artistic ambition – some of them are married and they have babies and they want the money. Their quality of problem is more like whether they should buy a beach house or whatever and I’m sweating for what I can find. I lost a penny loafer in Paris and had to get on a plane… but that’s a lot better than it was. Seeing The Walkmen on David Letterman on a tiny little TV in a very, very bad state with, you know, debris all over my room… it’s been difficult. I actually have a Walkmen t-shirt in my bag and I do like those guys – I’m just trying to sound tough and it feels good.

Really break this down for us, Stewart. Is Childballads a proper comeback? Are you truly serious about getting out there again?

SL: It will probably fall apart in about three months, I bet. Why not? Either that or it will stay together and it’ll happen. If it stays together, the dominos will fall in a really interesting place and I’d be really excited for that. It’s 50/50 – it may just implode, or we might pick up a pattern. People expect that of me – to get my shit together for six months and then fuck it up. It makes record executives sheathe their Montblancs [laughs]. I’d like their pens to come out with a little more ease from their breast pockets. But I’m in it for the long haul. I don’t know what will happen. I feel good and my ambition is bigger than it’s been since Jonathan Fire*Eater. For everything – for poetry, for writing, and girls, and girlfriends… that’s the bulk of it, but I could be a… what do you say over there? Tosser? Wanker? Prat? I could be a prat and point to some bands and stuff and ask for some royalties or something… I guess I feel like rock & roll owes me like a back cheque, but I’m not pretentious about it – I really don’t think I contributed that much. It just sucks to be this poor. It’s ridiculous. I work hard and… I don’t want to get into it. It’s the horse. The cart is filled with money, but the horse is a war horse.

Are you nonetheless proud of the huge influence you and Jonathan Fire*Eater had on the generation of New York bands that came after you? I’m thinking particularly of The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol…

SL: If they pay me my money, I’ll say, ‘Yeah.’ The Strokes owe me! I’m fucking around, but it is becoming apparent to me. There’s a woman making a documentary about all that and she started off with me, and now I think she’s making it only on me. But I don’t have any bitterness, it’s just rock & roll.

You can’t say you don’t have any bitterness! You do sound bitter.

SL: I was just taking the piss, as you say. What are you gonna do? Get an attitude about someone wearing the same clothes as I used to? Or parting their hair like I did? I wouldn’t be functional if I thought on those terms. But it is fun to fuck around with it. Everything I’ve said about The Walkmen, it’s like playing ping-pong. These things don’t govern my life. The money part does a bit, and that sometimes makes me think of other things because these bands like The Strokes and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, they’re millionaires. The Walkmen probably are too. Millionaires! I don’t understand that – it just doesn’t compute.

When Jonathan Fire*Eater signed with DreamWorks, that was a million dollar deal, wasn’t it?

SL: Yeah, but that got so fucking manipulated by the press. It was for a three-album deal that we didn’t complete and do you know how much we had to give to the lawyer? And to the agent? And we got our manager’s whole mouth re-constructed because he had no teeth. Eight hundred dollars a month – that was what I got paid. Less than the minimum wage. And we got $10,000 each upfront. That was fun, but it was gone very quickly. The whole thing with that deal was totally blown out of proportion. And please don’t think I’m bitter – I’m not, it’s just that sometimes the bare facts are depressing.

So you don’t feel like you’re owed something?

SL: No, not at all. I’m fucking around. If anything, I owe life. A lot. I’ve extracted a lot of life force from the natural flow of things and manipulated it for my own pleasure, and then set about planning and constructing my own downfall. I’ve been gone. No one owes me shit. I don’t look for handouts. At all. But the bare facts are that my best friends are millionaires. Maybe you don’t understand. We slept on the floor of the van… I don’t know. And maybe they’re not millionaires, but they’re very well-heeled and, I don’t know, it’s just bizarre to me more than anything else. I don’t have any resentment, or any sense of entitlement – it’s just bizarre and I’ll admit that it does sting a little bit. That’s it, and then I move on. And here I am. Wait, we’re about to go through a tunnel. I hope I don’t lose you.

Still there?

SL: Yup, I can hear you. Let me read you what it says on the back of this truck that’s in front of us: "If convicted murderers get life, why do innocent babies get executed? Think about it. Choose life."

That’s pretty heavy.

SL: That’s America, man. [pauses] Yeah, so I would like to start a full-on, blood-thirsty, going-for-the-jugular thing with The Walkmen. Just for fun.

What have you been doing all this time The Walkmen have been putting records out? There was stuff on the internet that said you were dead.

SL: When I read that, I was like, ‘Okay, time to start something.’ I’ve been studying. I’m a writer, I went back to college and studied poetry. And I fell in love with a woman and lived with her for five years, almost got married. I lived life, man. I cleaned up my act, fell again, got back up, dusted myself off. It’s the work of life. I was writing the whole time, taught myself guitar… There was a point when DreamWorks were going to fund me as a solo artist. They gave me money and I got this most precious guitar, and I got to meet Robbie Robertson from The Band. He was working as an A&R at DreamWorks. So depressing. He was never one of my heroes but, you know, he breathed the same air that Dylan did. First thing I asked him was, ‘What’s the name of your tailor?’ He hated that. Then I asked him how Richard [Manuel] was, because I forgot he killed himself in the 80s. My feet were way down in my mouth, but he was a prick and I don’t give a fuck about his Native American electronica bullshit. The Band sucked. They were great when they had Bob Dylan, but name a good record they ever did by themselves? So, what was I doing? All that stuff. And not paying attention to contemporary music. It’s kind of a drag keeping up and knowing what bands sound like what. There’s just so much shit. And then I’m told I have to be associated with MySpace and that’s a lot of pride to swallow. Everyone has to be associated with MySpace! Where did that come from? It’s so Orwellian. It’s like having a fucking microchip in your brain. It could get worse and it will get worse.

What music have you been into recently?

SL: I still love Royal Trux. For me they were the well to go to and they still are. They’re so misunderstood. No one will understand for 100 years how good they were.

A lot of people have been saying there’s a bit of Royal Trux about Childballads…

SL: They’re definitely an influence, but I’m trying not to copy them. I’d like to borrow more of their spirit and their bravery and their tenderness and their sincerity, though.

Mind if I ask you about drugs?

SL: Are you gonna take something? What do you need?

When you were away doing your own thing, everyone assumed you were stuck in some kind of heroin-induced hell. Is heroin something you’re still battling with?

SL: Is heroin something I’m still battling with? [pauses] Um, life is something I’ve had to battle with and, I don’t know, poppies are a part of that and… yeah, it’s no joke.

So you haven’t left it behind?

SL: I haven’t what?

Left it behind.

SL: It’s in the rear-view mirror – it’s back there but I’ve got a pretty healthy distance from it. But I don’t take it for granted. It could be round the next corner or whatever. But it’s not looking like it.

Did it suppress your creativity?

SL: Did it suppress my creativity? It suppressed my respiration. I don’t know. I don’t know. I think that, er… I mean, what do you call creativity? I suffered. Really. [pauses] I’m not gonna get into this. I went through an extremely disproportionate amount of suffering at a very young age, and I saw and did things and got into the wrong car and went into the wrong bars. Every place I went was the wrong place at the wrong time. I just got beatings – psychic beatings, over and over. So, when you come out of that, you’ve got something in your gut that ain’t ever gonna go away and that’s where my courage comes from.

Do you find it hard to trust people now?

SL: No, man. The reverse. That’s where my love comes from – I trust people. Even if they’re lying straight to my face, I trust their good nature or whatever.

Do people find you difficult to trust?

SL: Sure, yeah.

No more than any other person?

SL: I would say probably more. Addiction does things to your thought process and your points of relativity. Basically, it’s like all bets are off. You’re in a matrix. It’s not real and it seems like it doesn’t matter if you have to tell a little white lie, or six or seven, or 100. I was suffering a lot and I’m a much better person now. And a lot of it is directly because of it.

You’re 32 now, right?

SL: Yeah. You know about Saturn Return? I talk about it so much, I’ve got it down and it’s very like what we’ve been talking about in the past minute or so. In your late twenties Saturn returns and basically anything in your character that’s not nailed down, or any lids that are not closed, or if you’ve got any unfinished monkey business… all that shit gets thrown back in your face and strength grows exponentially. When you emerge from that, that’s when you’re ready to start playing again.

Have you emerged?

SL: Oh, hell yeah. It’s all in the rear-view mirror.

Tell us about Francis J. Child, who you named your new band after?

SL: He was some pretentious hack who recorded 300-and-something ballads and he said [adopts pompous voice], ‘There are exactly 376 songs, no more, no less, and I’ve collected all of them!’ He was an appropriator but he had some style. Our name has nothing to do with him – a little bit but not much. But I love his songs.

Is the cover of the Childballads record based on the Elizabeth Bishop book of poems, Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box?

SL: It is. And I think it looks good. I love Elizabeth Bishop – she’s one of my patron saints.

Isn’t she a bit like Emily Dickinson in that she didn’t get much recognition until after she died?

SL: She smokes Emily Dickinson! Eats Emily Dickinson for breakfast. Poetry and rock’n’roll are like stock – your stock comes up, your stock goes down.

Got a literary tip to end with?

SL: Ever read that T. S. Eliot poem ‘Gerontion’? It’s the one that starts, ‘Here I am, an old man in a dry month / Being read to by a boy, waiting for rain.’ It’s an old man reflecting on his life and inaction – the Hamlet thing – what he’s done, what he hasn’t done, and what he’s left undone. There’s this one section… I can’t read it without getting really worked up. He says history is too much too soon, and too much in too weaker hands. The timing was wrong. We had the right prayer but we were praying to the wrong god. You could apply it to so many things. It’s trying to do something but you keep missing. Everybody tries and everybody just gets fucked. Everybody tries and everybody falls. Basically it says that your motives are pure when you’re young and then they go south and decay. Then you’re left with a character that is not able to fit-a round peg for a square hole. You have most of the ingredients but not them all.